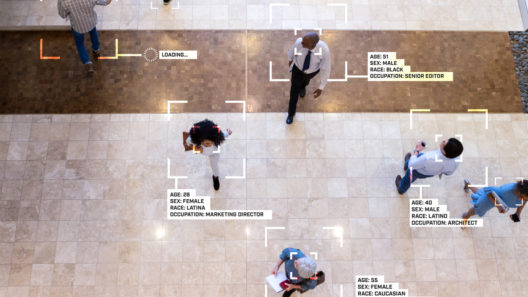

Facial recognition technology needs proper regulation – Court of Appeal

The appeal of R (Bridges) v Chief Constable of South Wales shows that, when it comes to facial recognition technology, the status quo cannot continue.

14 August 2020

Reading time: 8 minutes

On 11 August 2020, the Court of Appeal handed down a hotly anticipated judgement in the appeal of R (Bridges) v Chief Constable of South Wales [2020] EWCA Civ 1058. Mr Bridges, a privacy campaigner who was challenging the South Wales police trials of facial recognition technology, won his appeal, with the Court of Appeal concluding, among other things, that there is currently no adequate legal framework for the use of facial recognition technology.

What the judgement makes absolutely clear is that, when it comes to biometric data generally – and facial recognition technology, in particular – the status quo cannot continue.

For those of us at Matrix Chambers working on the Ada Lovelace Institute’s independent review of biometric data law and regulation – (the ‘Ryder Review‘) – the ruling was especially important. It is both a vindication of the decision to start this work, and a reminder of the importance of the task we have set ourselves.

Facial recognition technology has already become an almost totemic issue in the context of biometric data law. Just days before the Ryder Review launched in January 2020, the Metropolitan Police, unexpectedly and controversially, announced they would begin new trials of facial recognition technology in London. Perhaps emboldened by Mr Bridges having lost his case in the High Court a few months earlier, the law seemed to be on their side. This week’s ruling changes that dramatically.

The background to the Court of Appeal’s ruling began last year. Mr Bridges challenged the use of Live Automatic Facial Recognition (‘LAFR’) technology on crowds by South Wales Police, the first police force to conduct such trials. His challenge was supported by Liberty, the civil liberties campaigning group. In September 2019, the High Court rejected his claims and found that the South Wales Police’s use of the technology was lawful. Mr Bridges appealed.

For every lawyer watching the case, the exceptional importance of the appeal was obvious even before the hearing. Not only were Mr Bridges and the South Wales Police represented in the appeal, but also the Home Secretary, the Information Commissioner, the Surveillance Camera Commissioner, and the Police and Crime Commissioner for South Wales.

The constitution of the Court was also striking. It consisted of two of the most senior judges – the Master of the Rolls and the President of the Queen’s Bench Division – and Lord Justice Singh, who before becoming a judge had been a highly regarded human rights barrister – sometimes instructed by Liberty. But, interestingly, he had also acted for the Home Secretary and for the UK Government, taking an opposing position to Liberty, in the seminal UK biometrics case of Marper v UK.

In Mr Bridges’ case, the Court of Appeal gave a unanimous judgement, finding there to be three ways in which the South Wales Police’s use of LAFR technology was unlawful:

- It breaches Article 8 (the right to privacy) because it is not ‘in accordance with law’. In the Court of Appeal’s view, there are ‘fundamental deficiencies’ with the legal framework, which leaves too much discretion to individual police officers about how and where the technology is deployed.

- It breaches the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA) because the data protection impact assessment (DPIA) conducted under s.64 DPA failed properly to grapple with the Article 8 implications of the deployment of LAFR. Specifically, the DPIA failed properly to assess the risks to the rights and freedoms of individuals, and failed to address the measures envisaged to respond to the risks arising from the deficiencies in the legal framework.

- It breaches the public sector equality duty (PSED), because the police have taken no steps to satisfy themselves that the underlying software doesn’t contain bias on the basis of race and sex. As the Court observed, there is no reason to think that the software used by the South Wales Police does contain any such bias – but the whole purpose of the PSED is ‘to ensure that a public authority does not inadvertently overlook information which it should take into account’ and so it was unlawful for the police to have failed to obtain evidence of whether the software might contain inherent bias.

The software used by the South Wales Police is called AFR Locate. It operates by extracting faces from a live feed of a crowd, and automatically compares the extracted faces to faces on a watchlist. The watchlists were compiled by the South Wales Police to include suspects, missing and vulnerable persons, those whose presence at an event may be a cause for concern, and those of possible interest to the police for intelligence purposes.

If no match is detected between an extracted face and the watch list, the software automatically deletes the captured facial image. If a match is detected, the technology produces an alert and the person responsible for the technology, usually a police officer, then reviews the images to determine whether to intervene (for example, by speaking to the person identified, making an arrest, or informing other officers of a person’s presence).

As the Court of Appeal’s press summary explained, ‘SWP deployed AFR Locate on about 50 occasions between May 2017 and April 2019 at a variety of public events. These deployments were overt, rather than secret… AFR Locate is capable of scanning 50 faces per second. Over the 50 deployments undertaken in 2017 and 2018, it is estimated that around 500,000 faces may have been scanned. The overwhelming majority of faces scanned will be of persons not on a watchlist, and therefore will be automatically deleted.’ The Metropolitan Police deployed similar software to that used by the South Wales Police in their trials earlier this year. In light of the Court of Appeal ruling, every police force wanting to conduct trials will now need to reassess their position, to ensure they are not acting unlawfully.

Three features of particular interest emerge from the Court of Appeal’s judgement.

The first is a contextual one: the Court recognised that (contrary to the police’s submission) LAFR is not analogous to photographs or CCTV use, and different legal safeguards are therefore necessary. The differences arise because LAFR is a novel technology, which involves the automatic processing of digital information about a large number of individuals the vast majority of whom are of no interest to the police. The data that is processed is sensitive personal data within the DPA.

The second key finding (on which the Court’s determination as to privacy and data protection rights violations was reached) is that the current legal framework for the regulation of LAFR is woefully inadequate. The Court found that the DPA, Surveillance Camera Code of Practice and local police policies together provided no clear guidance on where LAFR could be used (including, for example, whether it should only be used in places where intelligence suggested it was likely that a person on a watch list would be present), or on who should be added to a watch list. These decisions were left to individual police officers’ discretion rather than finding any footing in law, and that is not, as the Court found, an appropriate legal basis for interfering with individuals’ data and privacy rights.

The Court accepted that it was not for them to design an appropriate legal framework but it did observe that ‘one of the elements of the system as operated in South Wales which is crucial… is that the data of anyone where there is no match with a person on the watchlist is automatically deleted without any human observation at all and that this takes place instantaneously’. The Court considered that ‘such automatic and almost instantaneous deletion is required for there to be an adequate legal framework’ for the use of LAFR, suggesting that such a feature will have to be enshrined in law if the police are, in future, able to deploy LAFR lawfully.

The third interesting feature for the future use of LAFR relates to how the PSED applies in circumstances where the information needed to discharge it – here, information as to the potential race or sex bias of the underlying software used for LAFR – is not available to the public authority. For reasons of commercial sensitivity, the software manufacturer would not provide the necessary data sets by which the algorithms had been trained, and those data sets were necessary for any assessment of whether there was unacceptable bias on the grounds of race or sex in the operation of the software.

But the Court found that without that information, the police were unable to discharge their PSED – and since the PSED is a non-delegable duty, the police are also not in a position to rely on an assessment by the manufacturer or others as to the absence of bias. In such circumstances, the police had failed to comply with the PSED and had failed, therefore ‘to reassure members of the public, whatever their race or sex, that their interests have been properly taken into account before policies are formulated or brought into effect’.

What does all of this mean for LAFR going forwards? Nothing in the Court of Appeal’s judgement suggests that use of LAFR is inevitably unlawful. But until a proper legal framework is in place, and until proper assessments of the impact of LAFR on individual rights and equality can be performed, its use (even in pilot form, as was occurring in South Wales) is unlawful. In the immediate term, and until better safeguards are in place, its use must be halted.

This is the first in a series of blog posts from the team carrying out an independent review of biometric data law and regulation – the ‘Ryder Review‘ commissioned by the Ada Lovelace Institute and chaired by Matthew Ryder QC.

The Ada Lovelace Institute commissioned Matthew Ryder QC to lead this independent review of the governance of biometrics data, which will examine the existing regulatory framework and identify options for reform that will protect people from misuse of their biometric data, such as facial characteristics, fingerprints, iris prints and DNA. Findings will be reported in spring 2021.

Related content

Ryder Review Advisory Board

Independent Advisory Board of specialists in law, ethics, technology, criminology, genetics and data protection advising on the Ryder Review.

The Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner: streamlined or eroded oversight?

When the direction of travel is towards more extensive use of biometrics and surveillance, do we need more or less oversight?