Where capital falls short

Exploring the gap between venture capital and climate justice

10 December 2024

Reading time: 89 minutes

Executive summary

Policymakers at the national and global level have suggested technology and innovation have a significant role to play to reduce global greenhouse emissions. This view was evident at COP 28, the annual conference on global climate change, and its side events where world leaders, businesses and civil society organisations made numerous references to the role that AI and other data-driven technologies can play in addressing climate change.[1]

Today, there is a surge in private venture capital (VC) investment in start-ups that are building ‘climate tech’ solutions – technologies that can be used to help societies mitigate against or adapt to climate change, some of which are AI and data-driven. While global VC investment is dropping, investment in climate tech start-ups has increased year on year and now equates to about 12 per cent of all VC investment worldwide.[2]

Given that climate change is a global challenge, it is crucial to ask who will benefit from these technologies. There is a risk that well-intentioned technologies built to address climate change may only benefit those living in higher-income countries, and that the incentive structures of VC-backed start-ups may not align with the needs or interests of people who are impacted by these technologies. This may perpetuate ‘climate injustice’ – a term that broadly encompasses the ways that those who have done least to cause climate change are those who are most likely to suffer from its consequences.

In this project, we wanted to understand how those funding and building climate tech solutions are thinking about issues around climate tech and climate justice. We spoke with 16 participants involved in building and/or investing in climate tech at UK VC firms and start-ups. Among those, the VC investors we spoke to engaged in both early and late-stage investing (pre-seed up to Series B and onwards). We sought to answer the following questions:

- What kinds of backgrounds and perspectives on the impacts of technology on climate change are VC funders and start-up founders bringing to their work?

- How do funders and founders think about and measure the positive climate impacts of the climate tech they are developing and funding? What motivates them to focus on certain aspects or measures of climate impact?

- How do funders and founders consider climate justice in their work on climate tech?

Overall, our findings show that the VC funding model for climate tech is not well suited for addressing issues of climate justice. This model of funding is ideal for products that can be quickly scaled and have ready-made markets of well-resourced consumers, which tends to mean solutions for climate mitigation for higher-income countries. This leaves out many climate tech solutions that would serve lower-income regions more susceptible to the harmful impacts of global climate change.

According to our findings:

- While we found that the VC funding model is not equipped to tackle issues of climate justice, we did find that the motivations of VC funders and start-up founders aren’t entirely misaligned with it.VC investors and start-up developers of climate tech solutions reported being driven by three broad types of motivations:

- a general concern about the climate crisis

- a belief that technology can be a significant part of the solution to the climate crisis

- a belief that the culture and fast pace of the technology industry can enable a unique contribution to effective climate action.

- While some investors we interviewed were confident VC-backed climate tech could address climate change and climate justice, others felt the VC funding model disincentivised investment in climate tech for lower-income countries.Some participants saw no trade-off between a successful VC-backed business and addressing climate change, noting VC funding may be one small part of a transition to developing climate tech that is well suited for rapid scale-up of production and distribution with less resource input. In this optimistic view, climate tech can reduce greenhouse gas emissions while retaining existing consumer lifestyles and choices.However, several VC funders expressed a less optimistic view about VC-backed climate tech, namely that it pushes a business model that is focused on innovation, competition and returns to an investor, which can distract from implementing existing solutions that work at smaller scales and which support lower-income regions. The VC funding model tends to optimise for products with ready-made markets of well-resourced consumers, which may exacerbate climate injustice.One start-up founder who mentioned the need for rapid scale-up discussed how one of their teams was initially interested in developing a product that would serve the needs of climate-affected individuals, but the commercial needs of the business encouraged them to focus on other markets for their proposed product, at least in the early stages.

- Public investment is essential for large, long-term climate tech projects.Some respondents expressed a belief that government investment in climate tech is a better solution than VC funding for ensuring the development and adoption of large, transformational projects, such as clean energy infrastructure or climate adaptation solutions that do not have a high return on investment. In their view, governments are better placed to invest in climate tech solutions that do not yet have a strong market incentive behind them (such as renewable energy usage).

- VC investors feel pressure to focus on technologies that reduce carbon emissions, which means that climate justice and climate adaptation are not priorities.VC funders and impact investors set their own definitions of climate impact, which determine which start-ups they invest in. Most of the VC funders we spoke with define ‘climate impact’ as reductions in climate emissions, and therefore almost exclusively focus on climate mitigation technologies (i.e. ones that reduce emissions) rather than climate adaptation solutions (i.e. technologies that help communities adapt to a changing climate). This means the VC funding model is unlikely to produce technologies that could benefit lower-income countries already experiencing climate change. Some VC funders reported setting an arbitrary threshold of ‘10 megatonnes of reduced CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) a year’. However, many admitted they do not have a reliable way to measure this reduction for those start-ups they invest in. Focusing on a single measure like CO2e reduction means favouring certain kinds of climate solutions over others – in particular, solutions that do not cater to the needs of lower-income countries.

- Among the VC funders we spoke with, few are thinking about climate justice in their funding decisions. Many participants described climate justice considerations as being a part of the language used by VC firms, but as secondary to other concerns around climate mitigation, and the growth and scalability of the business. Many VC funders reported feeling pressure from their limited partners (partners of the firm who provide the capital to invest) to demonstrate that their investments are reducing climate emissions, and so they don’t have time or capacity to focus on climate justice considerations. Some VC funders viewed climate justice considerations as being resolved by investing in founders with a strong commitment to these issues, or by hiring diverse teams that represent different regions. However, some start-up founders noted the incentives to scale their business rapidly to markets with ready-made consumers could still steer diverse teams with climate justice commitments towards climate tech solutions that do not serve those communities who may be most severely impacted.

- Many climate VC funders and start-up founders expressed a desire to do more on climate justice.Some VC funders and start-up founders did acknowledge an ambition to do more work that serves the needs of lower-income countries and communities, particularly those where they have experience of investment. There were some examples of start-ups and VC firms building climate tech solutions in lower-income countries that involved significant involvement and engagement with their local communities.For some start-up founders and VC funders, community engagement was described as an essential part of their business success. Some suggested that investments that encourage more community engagement could help address climate justice considerations around climate tech.

- VC firms and start-ups have a mixed view about the potential climate impacts of their use of AI and data.With regards to AI-for-climate technologies specifically, many VC firms and start-ups acknowledged there are major issues around the accessibility of these technologies for lower-income regions, where data scarcity may be a major barrier. Some also noted the benefits of AI may not outweigh the environmental impacts of these technologies for some communities.

How to read this paper

For all readers (15–20 minute read):

- Read the ‘Executive summary’ for key findings and a concise overview of the entire report’s main points and conclusions.

- Review the ‘Introduction’ to understand the context and importance of climate tech and its relationship to climate justice.

For policymakers working on climate (30–45 minutes):

- Start with the ‘Executive summary’ and ‘Introduction’.

- Focus on the ‘Attitudes towards market-based solutions to the climate crisis’ section to understand the role of private investment in climate solutions.

- Pay special attention to ‘The role of government and policy’ subsection within ‘Attitudes towards market-based solutions to the climate crisis’ for insights into how public and private sectors can complement each other.

- Review the ‘Conclusion’ for policy implications and recommendations.

For VC funders working on climate tech (45–60 minutes):

- Start with the ‘Executive summary’ and ‘Introduction’.

- Read ‘The funding and investing ecosystem in climate technology’ for context on the VC landscape in climate tech.

- Focus on ‘Considerations of climate impact’ to understand how climate impact is currently measured and perceived in the industry.

- Pay special attention to ‘Attitudes towards climate justice in the climate tech space’ for insights on how to incorporate climate justice considerations into investment decisions.

For start-ups building climate tech solutions (30–45 minutes):

- Start with the ‘Executive summary’ and ‘Introduction’.

- Read ‘What funders and founders think about climate tech’ to understand the motivations and perspectives of others in the field.

- Focus on ‘Considerations of climate impact’ to learn how VC funders evaluate climate impact and what they look for in start-ups.

- Review ‘Attitudes towards the impacts of AI and data on climate justice’ if your solution involves AI or data-driven technologies.

For non-profits working in climate tech (45–60 minutes):

- Start with the ‘Executive summary’ and ‘Introduction’.

- Pay special attention to ‘Attitudes towards climate justice in the climate tech space’ to understand how the private sector is (or isn’t) addressing climate justice concerns.

- Focus on the subsections discussing data impacts and environmental impacts of AI-for-climate within ‘What did different VC firms and start-ups mean by AI?’, as these may be particularly relevant to advocacy work.

- Review the ‘Conclusion’ for insights on how non-profits can collaborate with or influence the private sector in climate tech.

Glossary

- Venture capital (VC): A form of private equity financing provided to early-stage, high-potential companies in exchange for equity ownership.

- Limited partner (LP): An investor in a venture capital fund who provides capital but does not participate in managing the fund’s investments.

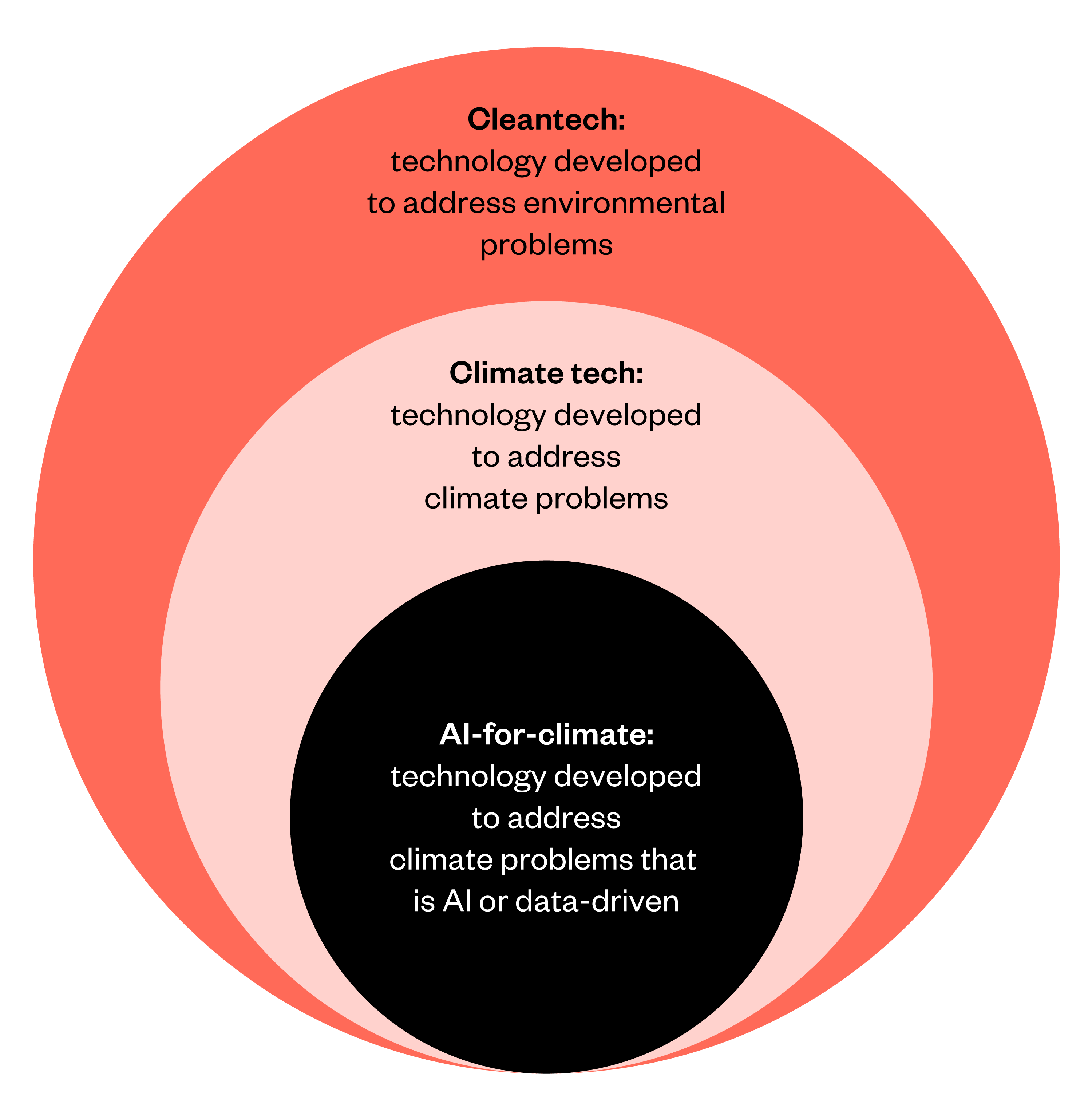

- Climate tech: Any kind of technology that can be used to help societies mitigate against or adapt to climate change. It includes a broad range of hardware and software solutions.

- Climate justice: A term that broadly encompasses striving for a world in which those who have done the least to cause climate change are the least likely to suffer from it. In contrast, climate injustice refers to the ways that those who have done least to cause climate change are those who are most likely to suffer from its impacts.

- General partner (GP): The firm or individual responsible for managing a venture capital fund and making investment decisions on behalf of limited partners.

- Impact investing: An investment strategy that aims to generate both financial returns and positive social or environmental impact.

- Venture capital builder: An organisation that systematically creates and launches multiple start-ups by developing business ideas internally and providing initial funding, resources and operational support to transform these ideas into viable companies.

- Venture capital funder/investor: An organisation that funds start-ups at different stages, from early-stage funding through to late stage. This term is often used to include venture builders, but funders/investors may not have as involved a role in the day-to-day operations of a start-up.

- Climate mitigation: Actions taken to reduce, remove or prevent greenhouse gas emissions to slow or stop global warming. Climate tech solutions aimed at mitigation seek to reduce, remove or prevent carbon emissions.

- Climate adaptation: Adjustments in ecological, social or economic systems in response to actual or expected climatic changes and their effects. Climate tech solutions aimed at adaptation seek to help communities or businesses adapt to emerging changes in the planet’s climate.

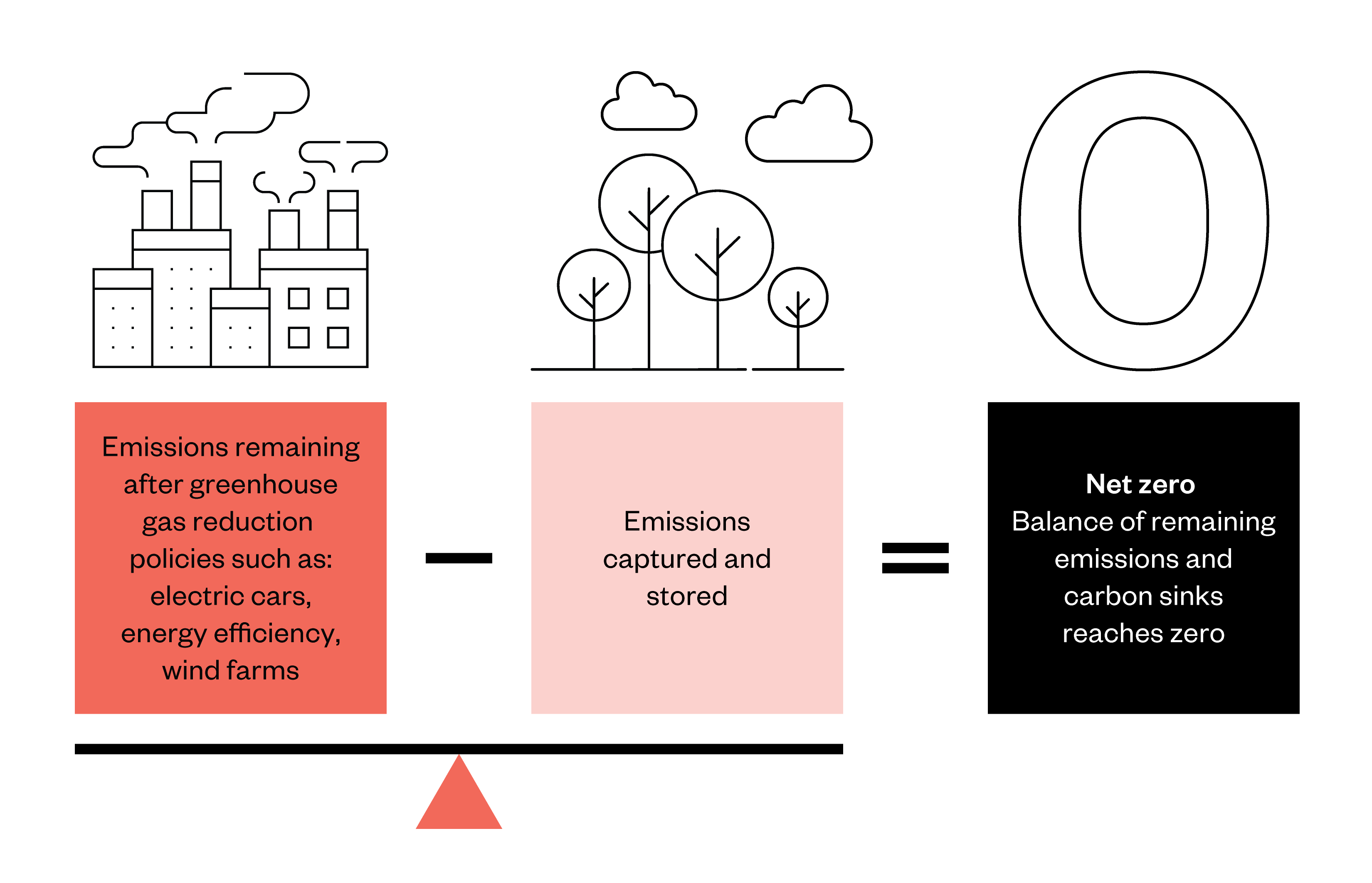

- Net zero: A state where the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere is balanced by an equivalent amount removed or offset.

- Carbon credits: Tradable permits representing the right to emit a specific amount of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases. Carbon credits are used by companies and individuals to offset their greenhouse gas emissions by purchasing credits that represent a reduction or removal of emissions elsewhere, which they use to compensate for their own carbon footprint.

- Carbon emissions: The release of carbon dioxide and other carbon-based greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, primarily from burning fossil fuels.

- Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e): A standard unit for measuring greenhouse gas emissions. It expresses the impact of different greenhouse gases in terms of the amount of CO2 that would create the same amount of warming.

Introduction

In recent years, the urgency of addressing climate change has catalysed a surge of innovation in climate technologies to aid in the transition to net zero. Policymakers at the national and global level have suggested technology and innovation have an enormous role to play to reduce global greenhouse emissions. This view was evident at COP 28, the annual conference on global climate change, and its side events where numerous references were made to the role that AI and other data-driven technologies can play in addressing climate change.[3]

‘Climate tech’ is any kind of technology that can be used to help societies mitigate against or adapt to climate change.[4] It includes a broad range of hardware and software solutions, such as battery storage; industrial processes to improve efficiency of carbon-intensive concrete and steel production; agricultural technologies to reduce fertiliser use and help farmers adjust to new weather patterns; and carbon capture.

Figure 1: Ecosystem of clean tech

In the last few years, there has been a surge in venture capital investment in start-ups that are building climate tech solutions. Venture capital investment is a form of private equity financing where investors provide capital to start-ups and early-stage companies with high growth potential in exchange for an ownership stake, typically aiming for a significant return on investment through an eventual exit strategy such as an acquisition or initial public offering. While VC is a relatively small asset class compared to other forms of investment, it has wielded outsized influence over the development of the technology sector. Many technology giants including Google, Meta and Uber trace their roots to early VC funding. Because VC firms typically invest during a company’s formative stages and take board seats, they help establish fundamental aspects of these organisations, like their business models and organisational culture.[5]

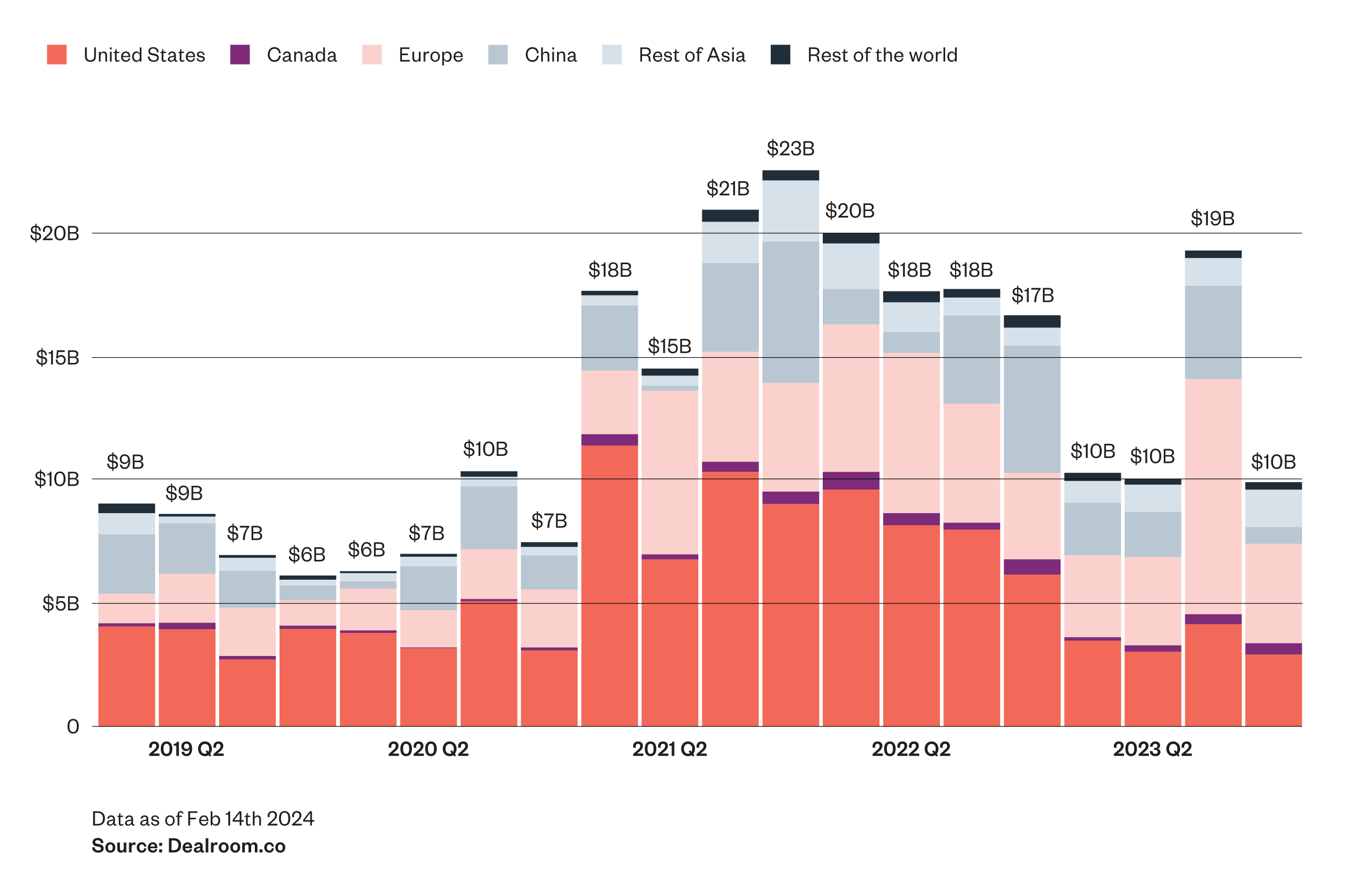

There is a significant amount of VC investment in climate technology companies. While global VC investment is dropping, investment in climate tech start-ups has increased year on year, now equating to about 12 per cent of all VC investment worldwide.[6] According to Dealroom.co, there was more than $48 billion of global investment in climate tech companies at different stages, with the majority coming from VC investors in Europe, the United States and China.[7]

Figure 2: Global VC investment into climate tech by region

While technology may play an important role in the transition to net zero, there are different schools of thought about what that role looks like. Many climate researchers and activists claim that we have the technology necessary to make the transition to a zero-carbon economy today, and that achieving that goal is primarily a question of funding, implementing and scaling available solutions.[8]

Others emphasise the need for further innovation in climate tech that will allow consumers to leave their behaviours unchanged. This school of thought focuses on the importance of markets and capitalism as a way of shifting to zero emissions. Bill Gates, who founded the climate-focused venture capital firm Breakthrough Energy, said during a press conference at COP 28:

‘I’m most optimistic about the incredible innovation. People’s willingness to pay for climate is limited … We need to really innovate.’[9]

Proponents of this perspective paint a seductive picture, where green technologies achieve economies of scale and replace fossil fuel-based technologies as the latter become relatively more expensive. In this world, electric cars replace fossil fuel cars, so-called ‘sustainable aviation fuel’ allows planes to fly with far less emissions, and data centres are run by small modular nuclear reactors that are more efficient and less polluting than existing power stations.

Net zero

Most climate targets set by national governments are aimed at achieving net zero. Net zero means that greenhouse gas emissions are counterbalanced by carbon-removal efforts, including climate technologies, so that the overall balance of emissions is zero. Carbon-removal efforts can include nature-based solutions, such as preserving existing trees and forests, or technologies to remove carbon from the air or from factory emissions, which can be stored or used. Countries’ current net zero strategies specify reducing emissions significantly by 2050, but even in the most ambitious climate targets they accept that there will be on average 18% of residual emissions that will require carbon-removal efforts. Residual emissions are emissions that are still present after carbon reduction efforts are complete.

Figure 3: What is net zero?

However, while climate change is a global challenge, its effects are not being felt equally by all. It is crucial to ask who will benefit from technologies built to address climate change. There is a risk that well-intentioned technologies may only benefit those living in higher-income countries, and that the incentive structures of venture-backed start-ups may not align with the needs or interests of people who are impacted by these technologies. This may raise a conflict with ‘climate justice’, which involves striving for a world in which those who have done the least to cause climate change are those who are the least likely to suffer because of it. In contrast, climate injustice refers to the ways that those who have done least to cause climate change are those who are most likely to suffer from it.

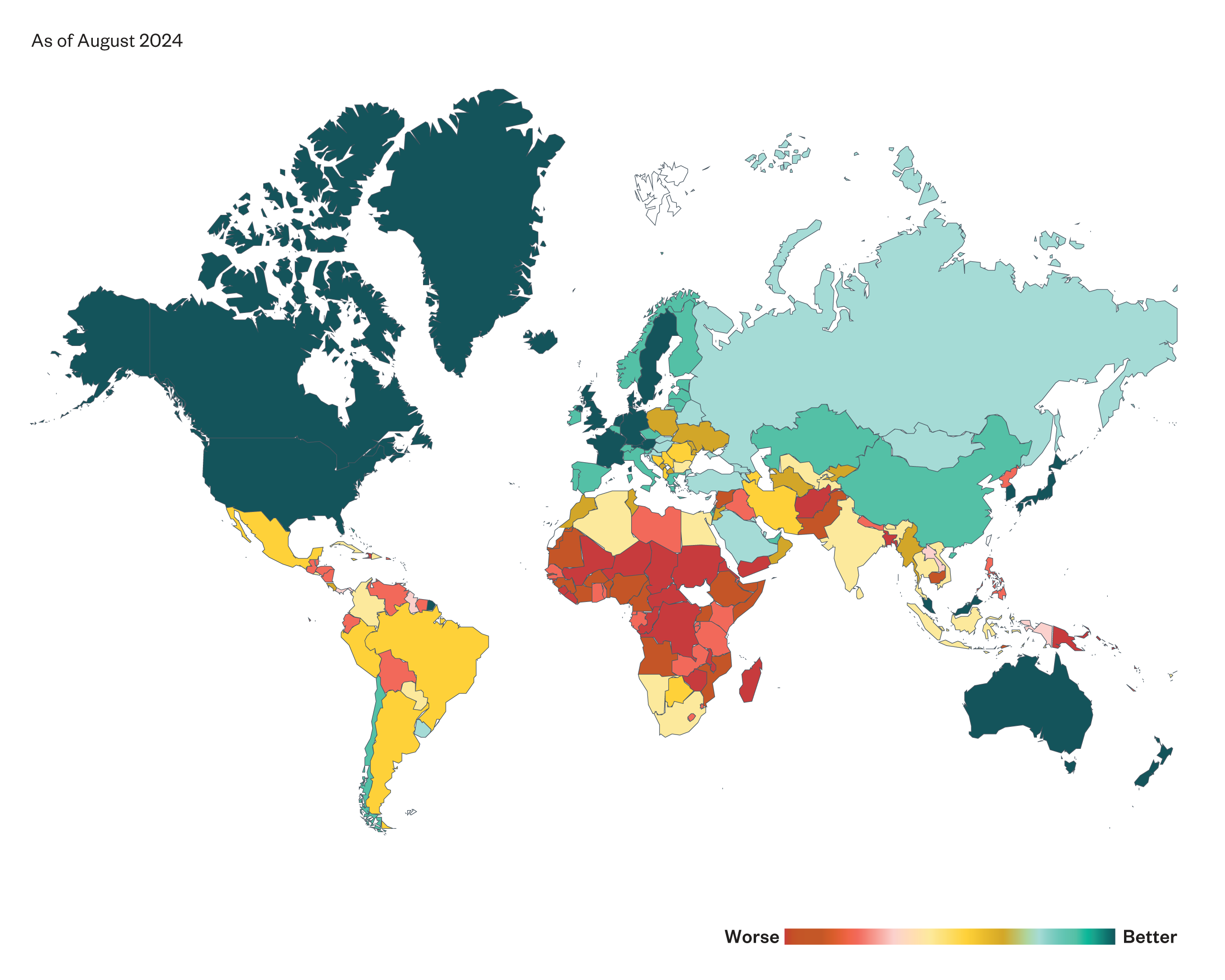

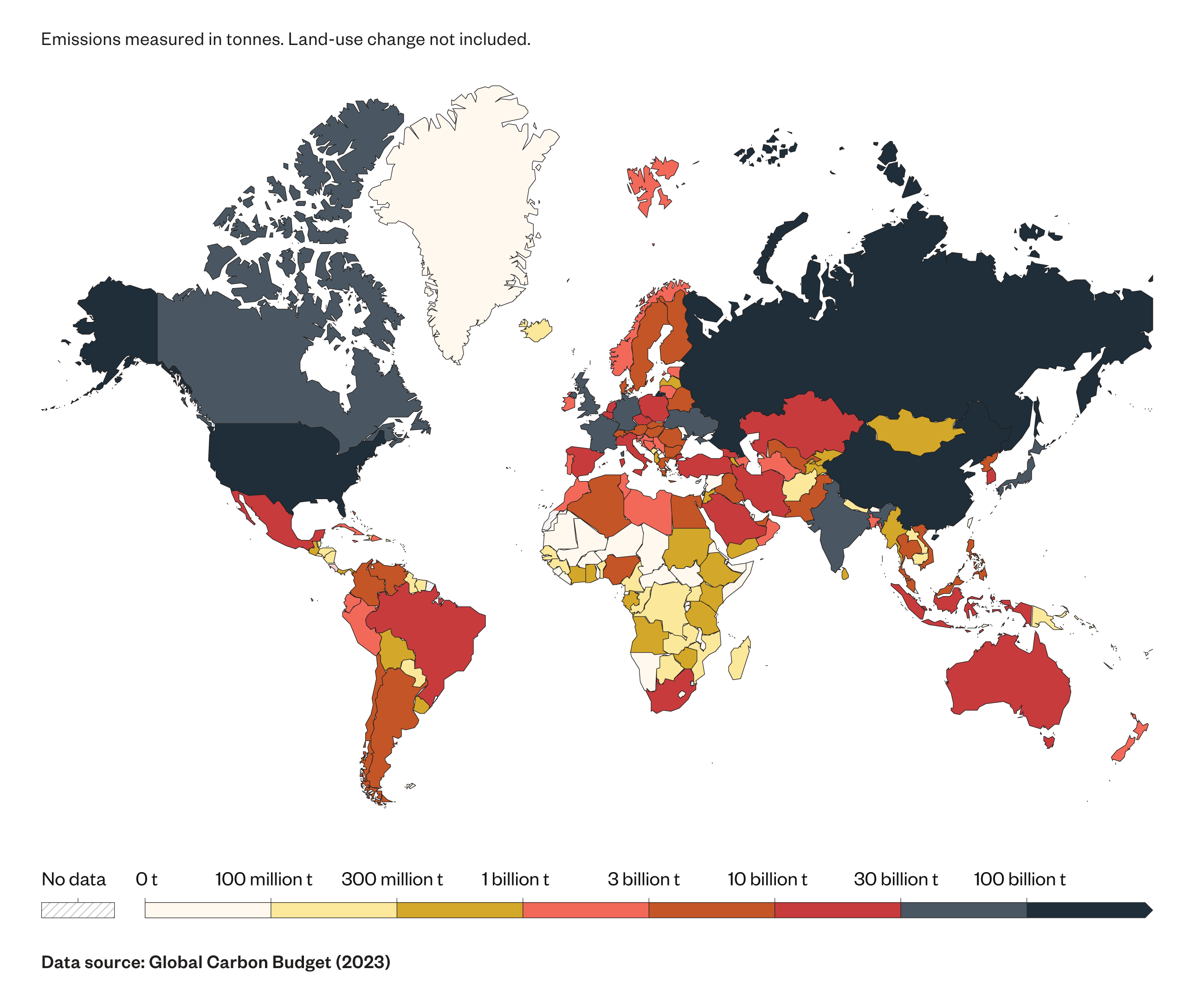

Today, many communities and countries with fewer resources are experiencing climate injustice. According to the University of Notre Dame’s ND-GAIN Country Index, the countries that are most vulnerable to climate change and other global challenges are predominantly in Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and South America.[10] These countries are also the least responsible for contributing global CO2 emissions.[11]

Climate justice is central to the contemporary conversation around climate. It is at the core of both the Paris Agreement and the COP 28 agreement for a ‘loss and damage fund’, a global fund to address damage caused by climate change, such as the mass displacement of people or loss of homes.[12]

Figure 4: University of Notre Dame ND-GAIN Country Index of countries that are most vulnerable to climate change

Figure 5: Map showing which countries are most responsible for CO2 emissions

Market-based solutions to climate change have a mixed history of supporting climate justice, especially if approached without care. Forest-based carbon credits are one example that have an enticing narrative – businesses pay to conserve forests in order to offset their carbon emissions. Since these forests are generally in lower-income countries, wealth is transferred from higher-income countries to support conservation. In practice, however, these schemes have been fraught. Indigenous residents of the forests have often faced persecution, displacement and even death as companies and governments claim the land for lucrative carbon credits. These schemes also often fail to deliver the carbon reductions they claim.[13]

The consequences of well-intentioned efforts such as forest-based carbon credits demonstrate why care and consideration need to be employed when developing new climate solutions. Solutions that look appealing may have unintended consequences. A similar dynamic has been present in the recent explosion of interest in AI and data-driven climate tech products. As investment and development in AI have grown, so have concerns about its impacts, particularly its disproportionate impacts on society’s most vulnerable.

Proposed AI solutions to climate challenges include technologies that can help predict the precise amount of fertiliser and water necessary to achieve a certain agricultural yield; the generation of more precise forecasts of solar and wind energy availability in order to better predict when non-renewable resources of energy will need to be fed into the grid; and advances in material sciences to create new types of batteries.[14] Given the unintended impacts that AI technologies can have, along with the history and challenges of the climate justice problem, particular care and caution should be used when deploying AI technologies in the climate space.

While some AI systems may help support climate adaptation and mitigation, they can also come with a significant energy and water footprint. Our 2023 report Net zero or net hero explored how the widespread use of AI technologies can have a serious climate impact.[15] These issues have only become worse since that report. As major companies have doubled down on training and developing generative AI products that serve hundreds of millions of users, the accompanying use of data centres and compute resources to train and run these products has caused water and energy usage to significantly increase.[16] [17] While a single Google search requires 0.5 mm of water in energy, ChatGPT consumes 500 mm of water for every 5–50 prompts.[18] [19] Today, most AI-for-climate solutions use far less computer-intensive methods than cutting-edge foundation models, but they may be used in the future in ways that could add to the problem.

Climate justice is integral to understanding and acting on climate change in an equitable way. As new climate technologies, especially AI-for-climate technologies, are being developed, it is vital to consider how they could affect those who have done least to contribute to climate change while suffering most from its effects. As global governments seek to determine what role they must play in fighting climate change, it is essential for them to understand the limits and drawbacks of market-driven approaches.[20] This is particularly important as some global governments have cut back on climate change investments to allow the private sector to fill the gap. In 2024, for example, one organisation lobbied the new Labour government to cut their £28 billion climate pledge in half and allow VC funding to support climate change initiatives for less cost.[21]

This project seeks to understand how the people seeking and funding climate tech solutions are thinking about the problem of climate justice. It focuses particularly on start-ups and VC firms in the climate impact space who have made commitments to achieving positive climate impact through building new technology businesses. VC firms in particular play an important role in setting incentives for business practices and market decisions that start-ups seeking investment may follow, and for driving business growth in certain sectors.

With this in mind, it is valuable to understand how both VC funders and start-up founders think about their contribution to achieving positive change, as well as how they go about trying to achieve this change. Our hope is this report can inform the conversation about the opportunities and limits of what kinds of climate action can be achieved through private impact investing in climate tech.

This report explores the following questions:

- What kinds of backgrounds and perspectives on the impacts of technology on climate change are VC funders and start-up founders bringing to their work?

- How do funders and founders think about and measure the positive climate impacts of the climate tech they are developing and funding? What motivates them to focus on certain aspects or measures of climate impact?

- How do funders and founders consider climate justice in their work on climate tech?

This report relies on interviews with 16 individuals involved in building and/or investing in climate tech at UK VC firms and start-ups, conducted between mid-July and mid-October 2023. The research focuses on VC investors in the impact investing space and founders of start-ups pursuing AI-for-climate solutions. For more information on our method, see our Methodology section below.

The funding and investing ecosystem in climate technology

This chapter provides a history of investments in climate tech and explains different funding models behind the investment in technology. It also offers background on how VC investment works and how it compares to other investment models.

A history of climate tech

Private investment in climate tech has ebbed and flowed considerably since the turn of the millennium. Climate tech had a rocky start as an object of VC investment in the early 2000s. The decade started with strong investment in environmental technologies, so-called clean tech. However, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology report found that VC firms lost half of their $25 billion investment in this area between 2006 and 2011, and concluded that VC funding was a poor fit for the kinds of environmental technologies being developed at the time.[22]

In the last few years, there has been a resurgence of interest and investment in climate tech. Global VC investment in climate tech reached its peak in 2021, when there were almost 5,000 deals totalling nearly $120 billion in investment. This has since sharply declined, in line with overall decline in VC investment. However, while the absolute numbers are down, VC investment in climate tech has been steadily increasing as a proportion of overall VC investment.[23]

VC investment in climate technology is mostly in North America, China and Europe; VC investments in the rest of the world account for less than 15 per cent of the total in recent years. Unequal access to climate tech is recognised as a challenge by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC includes specific provisions to cooperate on and share the development of climate technologies, particularly between higher-income and lower-income countries.[24]

Funding for climate tech start-ups

Start-up companies play a crucial role in the technology industry. As described by the VC funders and start-up founders we spoke with, they can act as catalysts for change, introducing novel technologies and solutions to existing problems. Compared to larger, more established companies, start-ups have an agile structure that allows them to respond quickly to market changes and emerging trends. They also often target specific, underserved market segments that larger companies might overlook. In the fast-paced environment of the technology industry, start-ups often integrate novel research developments into emerging technology products. This makes climate tech start-ups an interesting group to study, as often they are the companies seeking to create innovative technological solutions for climate mitigation or adaptation.

To succeed, start-ups need investment in different stages. Pre-seed or seed funding helps a start-up founder develop a proof of concept, or supports early market research and product development. When a company has developed a product, it may seek a Series A funding round to expand its product into new markets and to grow its user base. If successful, start-ups may seek additional funding rounds from growth-stage investors (usually called Series B, C, D, etc.) that help them refine their product and develop new products or prepare for an initial public offering (IPO). An IPO offers shares to the public that can be traded on a stock exchange, which offers an avenue for a return on investment for investors in previous rounds.

Across all stages, there is an ecosystem of funders who provide funding for start-ups developing climate tech. Each type of funder provides support to different, but sometimes overlapping, types of start-ups. The three types of funders outlined below are not exhaustive, but cover the major sources of funding for the climate tech start-ups we spoke with.

Public funding

The UK Government provides funding to new and established businesses, non-profits and universities for the development of new climate technologies. For instance, the UK Space Agency has had several rounds of funding to develop the technology necessary to make effective use of Earth Observation monitoring systems to address the causes and impacts of climate change.[25] The former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy[26] held several rounds of funding to support the development of innovations in several climate tech applications[27], including specific funding committed to developing new AI technologies for decarbonisation.[28] The UK Government also provides support indirectly through university research funding, which often provides the basis for technological innovation.[29]

Access to funding from the UK Government is competitive, and often reflects the political priorities of the party in power. One advantage of government funding of climate tech is that it allows for the development of climate tech without the need for an immediate commercial return on investment. More speculative technologies, or those that are effective but less commercially viable, might benefit from further development through government funding.

Philanthropic funding

Philanthropic funding for climate-related projects accounts for less than 2 per cent of philanthropic funding overall, but was steadily increasing in absolute terms until 2022, when philanthropic funding in general slowed in the face of global economic challenges.[30] Philanthropic funding for climate-related projects supports a variety of different projects, including the development and deployment of climate technology. Large-scale, well-established funders have been involved in this space, but often through funding smaller philanthropic organisations with a stronger climate or technical focus, such as the ClimateWorks Foundation or the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation.[31][32][33][34]

Philanthropic funding for climate tech supports non-commercial projects, such as those conducted through NGOs. Two AI-for-climate projects that have received philanthropic funding are Climate Policy Radar, which uses large language models to make global climate policy more easily searchable and accessible, and Open Climate Fix, which develops open-source machine learning models to do solar prediction and grid management.[35][36]

Venture capital funding

The VC model is perhaps the most well-known source of funding for start-ups. VC funding is a distinct model from traditional business funding. VC firms invest in products or projects based on their potential for rapid, explosive growth. The investments are high risk, and it is usually understood and accepted by VC firms that a high percentage of their investments will fail. VC investors usually acquire a portion of the business they are investing in, and often a place on its board.

Because VC investment demands fast growth, it has not always been seen as the best fit for financing climate tech in the past. Climate tech is often hardware-intensive, requiring significant upfront capital investment. That kind of investment can be risky and difficult to scale quickly. For this reason, VC funders have tended to favour software start-ups over hardware start-ups in general. This is one of the reasons for clean tech’s boom-and-bust cycle in the 2000s.[37]

How venture capital firms raise funds

In order to fund start-ups, VC firms must themselves raise rounds of capital. Funding can come from institutional investors, such as pension funds; governments, insurance companies, or foundations; or from individual investors. VC firms will raise a round of capital with specific timelines for investment and return, as well as other criteria influenced by their limited partners. Individual investors, known as high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), can also choose to invest independent of a VC fund.

Impact investing

This report focuses primarily on the world of VC impact investing for climate. Impact investing is defined by the Global Impact Investing Network as ‘investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and/or environmental impact alongside a financial return’.[38]

Impact investing is different from Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing. Impact investing emphasises the importance of generating positive impact by contributing to solutions, whereas ESG investing usually focuses on negative screening to prevent investment in companies that do not meet the ESG criteria. For example, a good impact investment for climate might be a start-up proposing a new type of battery technology. This could be a good impact investment because of the potential for increased use of renewable energy, reducing CO2 production. However, if the start-up had poor governance, such as a non-diverse leadership team, it might not meet ESG criteria.

An example of a company that meets good ESG criteria but might not be an impact investment is a rare-earth mining company. While the company may contribute funding to renewable mining efforts, have a strong governance board, and fund diversity equity and inclusion programmes, its core work may not ‘generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact’ in the eyes of many impact investors. Since 2019, there has been significant growth in the number of VC firms doing impact investing; today, there are 3,907 impact investors managing more than $1.5 trillion in assets.[39][40][41]

There are many different frameworks for understanding what different kinds of impact mean in practice. The UN Sustainable Development Goals are perhaps the best known.[42] Many climate impact VC firms use the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR) as an impact framework.[43] This 2021 EU law requires financial actors such as impact investors to provide information about sustainability risks and impacts in their investment processes. All EU financial actors are required to comply with the SFDR. However, they can choose their level of sustainability disclosure from one of three categories:

- Article 6 investments must report their sustainability risks, even if they are not sustainability focused.

- Article 8 investments, often called ‘light green’, must disclose how they ‘promote’ ESG characteristics.

- Article 9 investments, often called ‘dark green’, must disclose how sustainability is a goal of the investment.

The SFDR requires that companies seeking funding disclose whether or how they meet the criteria, but there is no oversight or regulation of whether investors meet the criteria. While SFDR was not intended to act as a labelling scheme, many climate impact VC firms use the label ‘Article 9’ to demonstrate that they are serious impact investors. This is true even of climate impact VC firms that are UK based, which will often describe themselves as ‘Article 9 equivalent’.

While the standards integrated into the SFDR are based on reductions to CO2 equivalents, some actors in this space have started to argue that we need to start thinking of climate impacts as going beyond just emission measurements. They maintain that justice and equity considerations also need to be integral to monitoring the climate impacts of investment.[44]

Findings

What funders and founders think about climate tech

This section unpacks the findings of our interviews with start-up founders and VC funders in climate tech. We wanted to learn about their backgrounds, their motivations for creating or investing in these technologies, and how they think about climate tech and climate justice. Interview participants highlighted three main motivations for investing or working in climate tech:

- They are mission driven. Many in this space are shifting from a traditional tech or business career to climate because of concern about the climate crisis. They want to feel that they are contributing to solutions.

- They believe that technology is a significant part of the solution. They see technology innovation as making an essential contribution in transitioning to a net-zero world.

- They think VC firms and climate tech start-ups have something to offer. They believe the low budgets and fast pace of VC-backed start-ups make a unique contribution to effective climate action.

On a mission to solve the climate crisis

Our interviews found that start-up founders building climate tech products and funders working in the climate impact venture space were largely driven by a mission to build technology solutions that address climate change. When asked how and why they had started in climate tech, respondents who had worked in tech or business settings spoke of how their concerns about climate or environmental impacts started to overwhelm their other career objectives. One person who had worked in business for decades before joining a climate venture builder and founding a start-up said, ‘I got to the point in my career where I was like, I just can’t be a part of environmental destruction any more. I want to actively use my time on the planet to try to change the system and solve the problem.’[45]

Many funders and founders who had made the transition from other tech or business areas had stories that echo those of other types of climate actors who transition to the climate space: something occurred that forced them to learn more about climate change, convincing them of the seriousness of the problem and motivating them to shift to a new focus. One VC funder described his transition from working on more general technology investments to climate impact funding:

‘I was working with this company on a project to try and discover the hidden sources of funding for deforestation … So we worked on that for nine months. And, you know, there was me looking at climate change every day for the nine months. And I thought, Okay, I need to stop messing around with tech and see what I can do on climate change full time for the rest of my life. So I took six months off, to kind of research and interview people and read, and do lots of experiments. And where I ended up was I realised that, you know, there’s a lot of amazing people who know what needs to be done. I don’t really know what needs to be done. I’ve read a few books on the subject, but there are people for whom this is their life’s work. So thought, what can I do to help them? And because we’ve worked a lot around money, a lot around start-ups, I thought, Okay, venture, that’s a good way of doing it.’[46]

Many VC funders and builders took pride in doing work that they considered far more meaningful than what they saw their peers doing in the technology industry. They specifically differentiated themselves from others in the VC funding space who might be engaged with ESG criteria, but were not taking the necessary steps to address fundamental societal problems: ‘You know, you have some wonderful smart people there and, like, can’t they try to do something about climate change?’[47]

Technology as a path to tackle climate change

Unsurprisingly, respondents saw the development of new technology as playing an important role in addressing climate change. Some respondents came from a tech company or VC background and were looking for ways to apply those skills to climate. These respondents expressed a more optimistic view of technology, and generally believed that technological solutions for climate change were important in a world where climate action overall is still very slow.

A slightly different angle on this came from those who had backgrounds working in other fields and saw problems in those fields that technology could help with. These types of respondents were often entrepreneurs who had backgrounds working on climate issues more generally and had worked in tech companies because they had recognised very specific ways that technology could help.

One entrepreneur who was working on carbon monitoring in forestry projects described their experiences as a researcher doing on-the-ground estimates of carbon storage in trees, a process they described as ‘walking around woods with a tape measure and counting trees and trying to identify them and then trying to make these really broad estimates about what was there’.[48] This person saw technology as a better solution than ‘sending armies of undergraduate research interns to wrap tape measures around trees’. Similarly, an entrepreneur who had a background working in construction explained how the process was very pen-and-paper based, with little digitisation. By their account, adopting even fairly basic digital technology in this field could offer benefits for environmental accounting.

The unique benefits of VC firms and start-ups

Some participants identified aspects of the culture of working in the technology industry that they considered particularly useful to developing climate solutions. They developed this perspective after working on environmental or climate problems in the NGO or third sector space, particularly working with projects in lower-income countries where climate impacts will be more keenly felt.

These participants expressed an interest in moving to the private climate tech sector because they thought it might be more effective than working in NGOs. One interviewee had previously worked for global development NGOs, including one where they had grown frustrated by the large amount of public money allocated to the development of a technology platform for disaster risk reduction for countries in the Global South. The interviewee noted how there were several organisations operating in this space with no technical expertise or knowledge to build these products, as well as no user participation and testing with the people affected by disasters. The interviewee attended ‘tech for good’ networking events while they worked for the NGO, and admired the way the entrepreneurs they encountered were ‘doing exactly what we tried to do on a very shoestring budget with virtually no money at all, but having a lot more progress in terms of actually validating their products and services and actually seeing the impact of it more immediately’.[49]

Discussion

It is important to understand people’s motivations for getting involved in the climate tech impact space in order to understand whether and how they might be willing to engage with concepts around climate justice. Given the rise of climate tech as a sector of VC investment, one question was whether entrepreneurs in this space were motivated by concern over climate, a desire to make money or some combination of the two.

Overall, people’s motivations for working in climate impact investment look remarkably similar to what we might expect from others working more broadly on climate change and policy. Actors in this space report getting into the area because of their deep-seated concern, in some cases bordering on anxiety, about climate change. Their decisions to pursue business-based and technology-based solutions to these problems stemmed from their belief that these were genuinely helpful solutions. Many reported that they would have been financially much better off if they had decided to pursue different kinds of careers.

It is notable that some of the interviewees had experience working on environmental or development issues in lower-income countries that are likely to experience stronger climate effects. This may impact some of their views around climate justice and the climate impacts of their work, as well as the extent and nature of their engagement with the concept of climate justice.

Attitudes towards market-based solutions to the climate crisis

Another set of findings from our interviews related to how VC firms and start-ups working on climate tech viewed the opportunities and limits of market-based solutions to the climate crisis.

Interviewees expressed a wide variation of views on this topic, ranging from those who saw market solutions as key to achieving climate solutions to those who recognised the limits of those solutions.

- Some saw market solutions, and those presented by VC firms in particular, as being key to developing effective climate solutions.

- There was some recognition that market-based solutions can produce some outcomes that could be suboptimal for achieving effective action on climate.

- Many respondents spoke of the importance of government and policy intervention as essential to the development of climate tech, particularly in places where radical shifts in a market are needed to incentivise the adoption of climate tech, and for lower-income markets where there is unlikely to be a significant financial return on investment.

Optimism about market-based technology solutions to the climate crisis

Many respondents expressed a strong degree of faith in the idea that effective climate action could be achieved through market-based solutions. As they saw it, providing climate solutions addresses a serious societal demand, and therefore should lead to successful business outcomes. They also expressed a degree of scepticism about the effectiveness of political or collective action on climate in the face of still widespread climate inaction and denial. As one person put it, their goal is to reduce emissions without their climate sceptic father-in-law noticing any changes in his lifestyle.[50]

Some saw unique properties of the VC investment model that made it appropriate for achieving positive climate change. One respondent identified the rapid scale-up of VC firms as linked in an essential way to the need for rapid scale-up of climate solutions:

‘So venture is a small, small part of the transition … It’s meant for companies that want to reach huge scale. And it only works for companies that have that intention … We want the companies we invest into, if they scale economically, we want the climate impact to scale with that … And we believe that is one extreme way of creating climate impact, of very quickly scaling.’[51]

This mirrors a similar view held by many world leaders around climate change. For example, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres, among others, has noted a rapid acceleration of climate action is necessary to avoid the worst effects of climate change.[52]

Some participants who had worked previously for NGOs or research organisations in lower-income countries saw business, particularly the nimble nature of VC-backed climate start-ups, as a way of generating faster, longer-lasting solutions with less resource input. They saw entrepreneurship as a sustainable path to achieving improvements in climate change, as it works with people’s existing lifestyles and choices.

The challenges of a market-based approach to climate tech

Even for those enthusiastic about the potential of technological and market-based solutions, there was some recognition of the limits of a market-based approach to developing climate tech. First, it is inherently competitive, which could lead to race dynamics and anti-competitive practices between different climate tech start-ups or even between different VC firms. According to some participants, this could reduce coordination between different companies and institutions adopting or building climate tech solutions, thereby reducing the effectiveness of climate tech solutions. One respondent who worked for a VC firm said, ‘I worry about the fact that the industry as a whole is not unified. I think as a climate investor, you have a moral responsibility to directing capital to the right places, and we should all be working together. And we’re not. We are more so than other sectors, but not enough.’[53]

Some founders expressed a tension between wanting success for any good climate solution, which could mean the success of competitors, and feeling commercial pressures to ensure their business remains viable. One founder talked about the massive improvement in available data in their field, and their ambivalence about the increased competition it could bring. They described a tension between wanting any good solution to be successful, while at the same time being aware that other successful solutions could be a direct competitor, with a negative impact on their own business: ‘[That’s] a tricky thing, I think, as a climate tech co-founder will be like … Well, I wish them well, but we’re also under commercial pressures to compete and survive.’[54]

At least one respondent acknowledged the central dilemma of climate tech and innovation: new innovation is necessary, but can distract from implementing and scaling the solutions already available. In the VC investment modelmost start-ups are expected to fail, which could make it more difficult to scale a wide variety of solutions. One leader at a venture builder described the problem:

‘What worries me is an overreliance on innovation, and thinking that you’re going to have all of these ideas created, and then the problem will be solved, where the real problem is actually implementing all the solutions we already have. We have tonnes of solutions already that we’re not using. And even these new solutions will then enter the pipeline of solutions that we’re not using. So false friend, innovation. It’s really important, we definitely need more innovation. But if we’re not creating routes to market at scale, then we’re going to just keep innovating and not doing.’[55]

The role of government and policy

Respondents saw private investment and market-based solutions as playing a role alongside other kinds of investments by the public sector. One VC investor described the role of private investment as working at different scales than investments from governments, from relatively small VC firms to large investors building infrastructure such as wind and solar farms. In their view, governments are best placed to fund ‘transformational innovation’ and large, long-term research projects. They noted, ‘Governments have to be the ones to do the big transformative stuff in terms of investing, for instance, in say, [nuclear] fusion, right? … Little venture capital funds like us, there’s no way we either have the money or the timescales to be investing in those kinds of things.’[56]

Other respondents noted that governments are also well placed to scale up the infrastructure – for example energy grids, housing developments, etc. – that may attract more green investment. One respondent noted that, currently, a significant amount of climate tech projects are subsidised by governments.

Discussion

While many respondents saw market-based solutions as playing an important role in achieving positive climate impacts, the majority of respondents did not see a market system that would work well independently of government funding and investment in large-scale, long-term transformational or infrastructural climate projects. VC funders and start-up founders we spoke with in the impact climate tech space understood technology and private investment to be making an important contribution to addressing climate change, but recognised some of the limitations of that contribution.

While one might think a strictly market-driven approach would create more competition and lead to the best solutions emerging, respondents we spoke with worried that may come at the cost of reduced coordination that might ultimately hamper the objectives of reducing carbon emissions.

Considerations of climate impact

Both VC firms and start-ups working on climate tech have developed specific methods for defining and tracking ‘climate impact’. How this impact is defined can tell us how investors in and developers of these technologies are considering climate justice. Climate impact VC firms are generally funded by limited partners who want to see evidence of the impact of their investments. Limited partners require VC funders to report on the kinds of impact they are achieving. In turn, climate impact VC firms put requirements on start-ups they fund to report on their climate impact.

Several themes emerged about how VC firms and start-ups define and measure climate impact:

- VC firms see climate impact as a necessary condition to fund a start-up, and something that a start-up must track throughout their funding relationship.

- Most VC firms are focused explicitly on climate tech that addresses climate mitigation solutions, rather than climate adaptation solutions.

- As a funding mechanism, the VC model works for businesses that can scale rapidly, which limits its utility for certain kinds of climate tech solutions that do not require or need to scale quickly.

- Building a narrative around their climate impact is important to VC firms. There is a lot of debate and discussion within the sector about how best to capture climate impact, with an acknowledgement that the way climate impact is measured may affect the kinds of solutions that receive financial support. VC firms see a start-up founder’s commitment to climate impact as an important way to measure and achieve climate impact.

The importance of demonstrating climate impact

VC funders we spoke with who work in climate impact funds said that a start-up’s plan to reduce climate harms was the most important and necessary condition to receive funding, more important than other criteria such as readiness to scale. These funders emphasised that the first question they asked of any potential investee was what their climate impact would be. If the start-up could not provide a convincing answer, climate impact VC funders would not consider the investment, even if the technology or finances of the start-up looked promising in other ways. As one VC funder explained:

‘Well, the first [question] we ask is to what extent will your company, once it’s properly trading, help reduce carbon emissions, or remove carbon from the atmosphere? And if they don’t do that, then we don’t invest in them. So that’s the first question. And you’re not eligible to go any further in a conversation with us unless you do that.’[57]

One VC funder described a pitch in which a start-up had developed an exciting new material that they claimed was going to have significant impact on mitigating climate change, but when the funder started to explore this in more depth they realised ‘that really the whole motivation for this business was nothing to do with the environment’.[58] They ultimately did not invest in the company. This example highlights the challenge many VC investors face – they have little data available from early-stage companies at the point of investment, making the start-up founder’s intention and motivation often the only guardrail and form of risk mitigation to ensure there will be no mission drift as the company grows and scales.’

Climate mitigation vs. climate adaptation

When we asked funders how they define and measure climate impact, they were overwhelmingly focused on funding climate mitigation solutions, i.e. technologies that reduce emissions. For many funders, they did not articulate how they arrived at climate mitigation as a focus – in their view, demonstrating a carbon emissions reduction was equivalent to positive climate impact.

Climate mitigation and climate adaptation

There are two general categories of plans to address the impacts of climate change: climate mitigation plans and climate adaptation plans.

Climate mitigation refers to any proposed strategy or plan that will reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore slow or stop global warming. Examples of climate mitigation strategies include the development of renewable energy, reducing livestock farming and consumption, and retrofitting homes for improved efficiency.

Climate adaptation refers to any plan or strategy that will help humans adapt to living on a changing planet with higher greenhouse gas emissions. Examples of climate adaptation strategies include flood controls, improved irrigation systems and providing shade in areas of extreme heat.

Other VC funders did note pressure from limited partners (LPs) who provide the funding to VC firms can incentivise them to focus on climate mitigation solutions. According to our participants, LPs often expect climate impacts to be reported in terms of carbon emissions reductions. One VC executive spoke of translating their in-house calculations of climate impact, which used measurements tailored to what each company was trying to achieve, into a more standardised set of measures that LPs asked for. While VC funders often emphasised that they would only raise funds from LPs whose values and commitment to impact they shared, they also had to respond to the specifics of the measurements LPs asked for.

According to our participants, the heavy focus on emissions reductions meant there was almost no engagement with technologies aimed at climate adaptation. Some respondents directly acknowledged the lack of focus on adaptation solutions, and expressed concern that there wasn’t more engagement with these from the climate tech community. They saw this as arising in part due to climate tech’s historical development, which was focused on renewables. They also pointed to the relative ease of having a North Star metric of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions, a standardised metric developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to create a measure for comparing the warming effects of various greenhouse gases beyond carbon dioxide.

One respondent working in a venture builder queried whether the nature of adaptation and resilience technologies might overall be a poor fit for the needs of VC investors:

‘The context really matters for adaptation. For adaptation, resilience, many of the solutions have to really fit the exposure and vulnerability profile of the assets or the people in an individual place. And actually, that isn’t well suited to scalable commercial solutions always.’[59]

In our interviews, VC funders appeared to carefully consider how the start-ups they fund can have a positive impact on climate. However, there are limitations in the ways that funders are currently thinking about this. First, they tend to focus mostly on emissions reductions through climate mitigation rather than adaptation solutions. Second, the fundamental logic of VC investment, which relies on rapid scale-up of a business, will not necessarily favour climate solutions that improve the lives of the most climate-affected individuals. VC investment may have a contribution to make to providing climate solutions, but it is important for other players in this area, such as governments, other types of funders and start-ups to recognise how reliance on VC funding may affect the ecosystem of climate solutions.

Market readiness and its impact on climate justice

The focus on climate mitigation is not the only way in which the nature of VC funding shapes the kinds of climate impacts that can be achieved. The VC model works well for rapidly scalable solutions, which means that readily accessible markets – ideally with well-resourced individuals who have an appetite for the technology – must already exist for a VC-backed product to succeed.

‘There are a lot of climate tech that are useful, but are not addressing a market need. So there has to be a market need. It can’t be that, “oh, this came out of the lab and we know it’s going to be useful one day”, but there’s no one that’s willing to pay for it. Because while we think that those are valuable, it’s just not going to get to the next stage. So there has to be a market for it. And there has to be somebody willing to pay for this type of service or product. Otherwise, it’s just gonna die at some stage or, you know, early on. So when we think about impact, we also try to think through how likely is this company going to commercialise what it’s creating.’[60]

Another VC funder described how the model of VC investing is high risk, high reward. Many investments will fail, so VC funders are incentivised to invest in companies that have a potential of high returns to offset any losses. This can mean that many climate tech start-ups that do not have potential for high return on investment are higher risk, and unlikely to receive investment.

‘Since we invest so early in companies, there’s a high chance a lot of them will fail. So if you look at statistics for venture funding, it follows a power law curve, where basically, like, two or three of the 30 investments will have 95% of the climate impact and economic impact of the fund. So that is the extreme side, which is that you do these 30 investments and 60% will die and not work out. And 40% will work in some way, and like, one or two of the 30 will have all the impact of the full fund. And when that happens, the company that has the main impact, that becomes the next, I don’t know, the Spotify of climate. We want that company to have that impact that the climate impact scales in the same way as the monetary.’[61]

The analogy of Spotify is an instructive one: while there may be ways of scaling a business by meeting the needs of underserved markets, businesses such as Spotify have successfully scaled by replacing a service to a relatively well-off, global market.

This can have serious impacts for climate justice. First, it means that VC-backed climate start-ups are not incentivised to launch in lower-income regions, where the return on investment may be less clear. Second, the lack of investment in climate adaptation solutions means that there is a lack of start-ups building climate tech solutions for countries experiencing the effects of climate change today.

Only one start-up founder we spoke with linked their climate impacts to operations in lower-or-middle income countries. They operated as a non-profit, and chose to operate in India because ‘even if we help UK to achieve its net zero goals in the broader scheme of things, the impact is going to be limited and we can have much bigger impact in a country that is heavily investing in solar energy but hasn’t really developed all the technologies yet … plus, you have many more people there.’[62]

When explicitly asked about operations in lower-income countries VC funders would point to the regulatory and logistical challenges that come along with working outside the UK or European context. In some cases, they were limited by the way they were incorporated and who they were allowed to fund as a result.

The need for rapid scale-up of a VC-funded start-up makes it inherently difficult to reach certain kinds of markets. One respondent from a venture builder discussed how one of their teams was initially interested in developing a product that would serve the needs of climate-affected individuals, but that the commercial needs of the business encouraged them to focus on other markets for their proposed product, at least in the early stages.

‘One of the few adaptation products we’ve had, the people who were developing it really, really wanted [redacted Middle Eastern country] as their first market. They were developing a kind of a watch-based risk-based monitor, to help people identify when they’re in danger of coming close to extreme heat conditions that were dangerous for their health. And to help people then know to remove themselves from that situation or to manage it in a certain way. And their primary focus was … on vulnerable people who were outdoor workers, particularly in the Middle East, which tended to be also poor demographics … It was quite tricky, because it was a very good kind of climate-justice orientated solution, but from a commercial perspective, that was not the best first market to start for, because it was going to be impossible to mobilise and get their product out there. Although there could be an impact later on.’[63]

Building a narrative around and measuring climate impact through metrics and founder commitment

Communicating climate impact is important to both climate impact VC firms and climate tech start-ups. VC firms and especially venture builders put a lot of emphasis on start-ups creating a narrative around the climate impact of the work. Many early-stage start-up founders and funders made the point that getting exact numbers around possible climate impacts was difficult, or even impossible, at the earliest stages of their work. But they emphasised the importance of constructing a strong story around climate, both to help the start-up sell itself and to understand what kinds of measures to put against their impact in future. As one VC builder said, ‘I [tell the founder], perfect the argument, not the numbers.’[64]

The way climate impact is framed affects the kinds of measures start-ups need to demonstrate their impact to funders, governments and the public. Several VC firms used the same threshold of reduced tonnes of CO2e that would result from the start-up’s business. This threshold was generally set at 10 megatonnes a year of reduced emissions. This target was seen as achievable, but ambitious. One VC pointed out that Tesla had only recently reported 10 megatonne CO2e impact.[65]

‘We have an impact threshold, which is that every company has to have some path towards 10 megatonnes of CO2 emissions reductions per year, for a period of 10 years. They don’t have to get to this in five years, or 10 years, but at some point, they have to get to that … I mean, it’s honestly, it’s a very high threshold. Like, Tesla, that was their impact last year, 10 megatonnes, they’ve been around 20 years. So if they can get to that threshold, that’s good enough for us.’[66]

‘So we went for the thing that we can call a measure, which is tonnes of CO2e. So we’ve got a low watermark, that people that we invest in need to get above that 10 megatonnes a year. So they need to be able to, at some point, get to 10 megatonnes a year. And so we don’t do like a full deep dive into “how many planes did you take last year?”.’[67]

The perceived value of a target like 10 megatonne CO2e reduction is in its clarity and simplicity. However, some founders saw potential problems with focusing on a target that was so specific. They said that trying to calculate such a specific number with a new and uncertain business might not be an honest reflection of what the business was likely to achieve.

One VC funder described estimating climate impacts as ‘so hilariously uncertain’ that to attempt to pinpoint the number exactly would be equivalent of lying to themselves about what a start-up was achieving.[68] Another VC funder pointed to the diversity of impacts their start-ups were expected to have, and the importance of finding the right performance indicator for each start-up.[69] This VC funder expressed some frustration at having to translate these diverse measures into CO2e for different audiences. They felt that the subtlety was lost, but also that translating everything into CO2e required making sets of assumptions that made ‘the temptation far too great to play around with those statistics’ to make a company look better.[70]

Lastly, many VC firms we spoke with described the importance of a founder’s demonstrated commitment to climate impact as an important measure. When asked how they would ensure that climate impact goals are reached, both VC funders and start-up founders emphasised the climate commitments of founders in this space. VC funders often cited this commitment as one of the ways they would ensure the continued climate impact of a business:

‘So for us, impact is kind of baked into everything we do. When we choose our venture builder in the first place, we spend a lot of time trying to work out their motivations to do good in the world. We think that impact-driven entrepreneurs are … gonna be sort of the kinds of people that see something through because they’re driven not just by … an intrinsic desire for status and money and things, but they also desire to have that sort of positive externalities and those pro-social things.’[71]

Discussion

The ways that funders and founders think about what climate impact means shapes the kinds of solutions they seek and fund. Funders told us that they were almost exclusively focused on climate mitigation as a climate solution.

There is almost no investment from climate impact VC funders we spoke to in climate adaptation technologies, which is acknowledged to varying extents by different funders. In many ways, this reflects the broader conversation around climate, where the focus has remained on mitigation to the detriment of adaptation. But it’s important to acknowledge the impacts this can have in terms of climate justice. The impacts of the climate crisis are expected to worsen sharply in the coming years, with the worst consequences suffered by those with the fewest resources to bear them. Failure to develop appropriate adaptation technologies will impact everyone, but impact the worst-off the hardest.

It is important to be careful about how climate tech engages with adaptation technologies, however. As demonstrated by the story of the founders who wanted to develop a heat warning system, but were told to concentrate first on well-developed markets, commercial adaptation solutions are likely to serve those who can pay for them. This could exacerbate how the impacts of climate change are felt.

VC firms, and in turn start-ups, are under pressure from their investors, particularly limited partners, to continually evidence their climate impacts. Limited partners are often focused on easily comparable and understandable statistics, which can affect the kinds of projects that are developed and funded. Shifting the objectives of limited partners could shift the objectives and practices of VC firms, and by extension, those of start-ups.

Attitudes towards climate justice in the climate tech space

In our interviews, we asked climate impact VC funders and start-up founders how they considered climate justice in their decisions around who to fund and what to build. We heard three broad types of responses:

- Disengagement with the concept, though some acknowledged that it’s a ‘thing’.

- Diverse teams being seen as a way of building climate justice.

- Engagement with climate justice issues, but not labelled as such.

Lack of engagement with climate justice

Many conversations around climate action now involve some acknowledgement of the different impacts of climate change on different parts of the population, both globally and locally. However, this orientation towards centring climate justice impacts does not seem to have made significant inroads into thinking about climate among venture capitalists. A respondent who works in a venture builder explained that people were aware of the term, and might use it to frame a project, but without it being a main motivator or framework for thinking:

‘It’s not really part of the language of the venture start-up space in the way that it is part of the academia and the NGO world. People will use it in a narrative sense. People are always trying to build narratives around their start-ups, but to be honest … if you ask someone, Are you interested in climate justice? Of course, people are gonna say yes and, yeah, we are. But is it one of the key pieces of vocabulary that are used to describe the opportunity space, to mobilise action? I would say it’s actually relatively secondary.’[72]

Another venture builder, when asked whether climate justice issues came up as part of the training they do for start-ups, explained that they talked about climate justice ‘upfront’ as one of the key trends in the climate space, so that start-ups are familiar with the term and how they might use it in framing their projects to appeal to certain audiences.[73] However, this training did not emphasise it as key to understanding climate issues, and was not something the respondent carried through with a start-up into the further development of the business.

One start-up founder described the challenges of centring climate justice concerns in the context of the rapid scaling of the VC-funded start-ups, stating that ‘the only spaces [climate justice and inequality] come up are in very forward-thinking’ firms.[74] According to this respondent, ‘Even in those spaces, it’s really deprioritised in favour of growth. And I think that is just because in the start-up space, things happen so quickly, the companies disappear so quickly, everybody is so focused on making it to next year. This stuff kind of gets lost in the ether.’[75]

This reflected the perspective raised by a lot of the VC funders, who emphasised their relatively limited influence with shaping what start-ups choose to work on. Many funders felt a significant amount of pressure to demonstrate to their limited partners that their investments were reducing emissions and delivering returns.

Diverse teams as climate justice

When asked directly about the ways that they engaged with climate justice, many referenced the importance of building diverse teams, which could provide different perspectives and possibly different solutions. One respondent noted one ‘parallel’ to climate justice they are really concerned about is ‘trying to make sure that the people who are climate innovators are not just like your usual suspects’.[76] According to this respondent, ‘I think that if we get more diverse groups of people being innovators, we’re also going to get more different kinds of ideas, and more ideas about what the kind of co-benefits of things that we could be doing are’.[77]

Another respondent also cited ‘diversity in innovation spaces’ as an objective related to climate justice. ‘When things are all just designed and innovated by one group, it’s really unfair for the rest of the Earth, because it’s only designed for them. So that is something that does recur. And I think funders are thinking about that … Most accelerators I’ve been on, there has been at least a session on kind of fairness in the innovation space.’[78]

Respondents did acknowledge that further diversity in founding teams might not be the key to unlocking climate justice issues. But the frequency with which team diversity came up suggests that it was often seen as making a meaningful contribution. However, while diversity in this space is an important step in the right direction for many reasons, more diverse teams will struggle to bring those unique perspectives to their business if incentives and structures are aligned towards different goals such as growth and return on investment.

Addressing climate justice under a different name

Some VC firms said that they would like to do more work that served the needs of lower-income countries and communities, particularly in cases where they had had some experience of investment. While these businesses could have reasonably been described as having a climate justice orientation, VC funders we spoke with did not describe them as such.

For example, one funder described their experience in funding a clean energy infrastructure start-up in a lower-income country. This project used an innovative technology to provide clean energy in a place where people relied primarily on diesel as fuel. According to the funder, the new energy project would have multiple co-benefits for the people living in the area, including reduced pollution and energy independence that could ‘unlock their economy’.[79]This project speaks to a number of climate justice concerns, but the VC funder did not frame it in this way.

From a climate justice perspective, it is also important to carefully consider the negative impacts of new climate technology projects on the communities where they’ll be implemented, particularly when those communities are in lower-income countries. When asked about how they considered and evaluated the impacts of the project on the local community, the VC firm working on the renewable energy project said they didn’t have a systematic process in place, but described a process that involved consulting with a number of local actors: