New rules?

Lessons for AI regulation from the governance of other high-tech sectors

31 October 2024

Reading time: 98 minutes

Executive summary

The UK has seen a surge in the adoption of AI technologies across the private and public sectors in recent years, including in domains like education, healthcare and criminal justice. As AI is increasingly used to make highly consequential decisions about people’s lives, governments around the globe have started to propose and pass legislation to regulate these technologies.

While regulating AI brings its own challenges, it is not the first time that policymakers have grappled with governing highly complex technologies that play a central role in society and the economy. However, many of the current policy debates around AI typically seek to start from first principles rather than drawing on the lessons from previous attempts to regulate other domains.

This report looks at the regulatory structures, approaches and objectives of three other UK regulatory regimes that are commonly compared with AI in policy discussions:

- Pharmaceuticals for human use

- Financial services (with a focus on consumer protection and financial stability)

- Climate change mitigation (specifically the carbon emissions regime established by the Climate Change Act 2008)

Each of these areas uses regulation – statutory rules imposed by the Government on individuals and companies – as part of a wider governance regime, which may include other mechanisms for overseeing behaviour and practice like professionalised norms, standards and non-binding commitments. Regulation can shape governance – for example, statutory rules can foster the development of certain professional norms. In this paper, we focus on regulation specifically, given the UK Government’s interest in developing a wider AI regulatory framework.

These areas do not map neatly onto AI regulation – but they do have several features, objectives, and mechanisms that can inform regulatory proposals for AI. These include common regulatory functions that are also being proposed in AI legislation, such as pre-market assessment; monitoring harms to individuals and society; and transparency requirements. They also cover a mixture of considerations around product safety and systemic impacts of a regulated domain, both of which are common features of AI regulatory proposals in the UK and EU.

The political economies of these sectors have similar dynamics to those of AI technologies, including the need to regulate a small number of powerful companies. These sectors share some common features with AI technologies, including opacity of how complex systems operate, the fast-paced development of novel products and a significant amount of uncertainty around their impacts.

To examine these regulatory regimes in more detail and uncover learnings for the development of AI regulation, we commissioned experts to create a case study on each domain based on five research questions:

- What are the objectives of regulation in these different sectors? What does regulation seek to achieve?

- What mechanisms have regulators implemented in these different sectors to meet these objectives?

- How has regulation facilitated the creation of public benefit and how is this defined?

- How have liability and compliance burdens been distributed across the value chain in these sectors?

- How have any restrictions on access and proliferation impacted research and the size of the market?

Lessons for policymakers

Drawing on a thematic analysis of these three regulatory regimes, and the associated case studies, [1] [2] [3] this report identifies common challenges and proposes lessons that can be applied to AI technologies. These lessons can help the UK Government ensure that domestic AI regulation is both robust and future-proofed.

Lesson 1: Delivering a pragmatic regulatory framework for AI will require independent institutions that have the required resources and statutory backing to operate effectively, strategically and with appropriate flexibility over the long term.

This does not require removing or replacing existing AI governance initiatives in the UK.

Many of the building blocks of a wider AI governance regime are already in place.

These include the AI Safety Institute (AISI); the voluntary commitments from foundation model developers secured by the previous Government; the ‘central functions’ established following the March 2023 white paper on AI regulation; and existing ‘horizontal’ regulation such as the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Equality Act 2010, which provide important protections[4] to people affected by AI.

Tying these disparate elements together into a coherent framework will require the introduction of new powers, resources and statutory underpinning for regulators and their supporting institutional architecture (such as AISI and the central functions). It will mean safeguarding, and building on, existing legal protections rather than removing or watering them down. Existing UK regulatory regimes were not created fully formed but instead emerged over time in response to growing harm. Following these precedents, policymakers should feel confident in pre-emptively establishing and empowering regulatory authorities to take action on AI products and services, in the knowledge that their functions can be developed and iterated in response to new evidence.

Lesson 2: Building and maintaining confidence in critical services and technologies requires the implementation of assurance mechanisms that can demonstrate they are safe, reliable and trustworthy.

As in the pharmaceutical sector, a regulatory approach that assesses the efficacy and safety of AI products and services may help the UK become a leader in assessing AI risks. As in the climate and financial services sectors, regulation for AI will have to address not only individual company behaviour but also the systemic impacts of these systems, which may also require the development of methods analogous to stress testing in banking.

While private actors have a role to play in providing assurance across these dimensions, the experience of other regulatory regimes suggests that industry-led or voluntary initiatives are no substitute for robust public oversight delivered by regulators with meaningful enforcement powers. To avoid conflicts of interest and the ‘gaming’ of regulatory mechanisms, the development of metrics and methods for assurance should be led by regulators and independent entities, and not by regulated entities.

Lesson 3: Sectoral regulators can be less effective if their objectives conflict with the goal of ensuring technologies, products, and services are safe, effective, and trustworthy.

Proposals for the regulation of AI and related technologies sometimes include provisions that mandate regulators to promote objectives such as innovation, competitiveness or economic growth, mirroring trends in other sectors including pharmaceuticals and finance. The evidence from these other sectors suggests that introducing secondary objectives around innovation and competitiveness can be counterproductive, compromising safety efforts without yielding significant public benefit.

Lesson 4: To help mitigate the risk of institutions becoming unduly influenced by particular interests, mature governance regimes should include an ecosystem of independent institutions that can hold each other accountable and act as effective checks and balances.

Beyond the core of regulatory institutions, wider stakeholders in civil society and academia also play an important role in the regulatory ecosystem of the three sectors we reviewed. These actors support activities such as critically assessing regulatory methods and advocate on behalf of affected persons.

Lesson 5: Post-market monitoring measures can help ensure that risks of emerging technologies and sectors are better understood, prevented and mitigated.

There is a strong case for post-market monitoring of AI systems because their performance and behaviour can change with new data. Similarly, assurances of the performance of an AI system in one context may not provide much clarity about how well that system will function in other contexts. Our research shows that post-market monitoring has not been implemented particularly effectively in some sectors but that better resourcing can help improve implementation.

A post-market monitoring and reporting regime for AI will therefore need to be developed over time to establish what works best. This should be a priority area for further policy research and development within the UK Government. The regulatory ecosystem will need to be equipped with powers and duties to request information about, and conduct independent investigations into, specific incidences of harm as well as the longer-term structural impacts of the integration of these systems into our society and economy.

Lesson 6: Successful regulatory regimes incorporate mechanisms for redress and dispute resolution for individuals affected by a technology, service or product.

In AI regulation, there is a need for redress and dispute-resolution mechanisms in sectors where there are no formal mechanisms. Adopting an ombudsman-style model, which has been effective in other sectors, could act as a complement to other central functions that the Government has set out. This model could support individuals in resolving their complaints and help direct them to appropriate regulators. It could also provide the Government and regulators with important insights about the harms people are experiencing, and whether they are effectively securing redress.

How to read this report

This report draws insights from the three case studies of regulated domains – pharmaceuticals for human use,[5] climate change mitigation,[6] and financial services[7] – to inform regulation of AI technologies. Each case study draws on interviews and workshops with experts from each domain, along with literature reviews on the regulation of those areas.

Depending on your background and interests, we recommend different reading strategies.

For all readers (10–15 minute read):

- Executive summary for key findings. This provides a concise overview of the report’s main points and conclusions.

- ‘Findings’ for an overview of common themes and key findings across the three regulated domains and their implications for AI regulation.

If you are a policymaker or regulator…

…and you’re working on AI regulation (30–45 minutes):

- ‘Executive summary’ for key findings. This provides a concise overview of the entire report’s main points and conclusions.

- ‘The Regulatory challenge of AI’ to understand some of the features of AI technologies that make regulating this technology area so difficult.

- ‘Overview of selected regulatory regimes’ for a high-level overview of how the objectives, history and mechanisms of the three selected regulatory domains. This chapter provides an overview of how regulation of pharmaceuticals, climate change mitigation and financial services operate in the UK.

- ‘Findings’ for an overview of common themes and key findings across the three regulated domains and their implications for AI regulation.

…and you’re interested in more detail on these regulated domains (60–90 minutes):

- Start with the ‘Overview of selected regulatory regimes’ for a high-level overview.

- Then read each of the case studies [8] [9] [10] for a deeper read on the specific regulated domain.

- Return to ‘Findings’ for an overview of common themes and key findings across the three regulated domains and their implications for AI regulation.

Introduction

AI systems are being rapidly integrated into many aspects of our lives. There is no one accepted or universal definition of AI. Broadly, AI refers to the science of creating computer systems designed to carry out tasks previously considered to require human behaviour, intervention or oversight.

AI systems can be used to complement a human decision, and in some cases, fully automate it. Their use in real-world contexts is increasingly widespread. The NHS has employed AI to support health diagnostics,[11] while local authorities are using it to help inform decisions about social care.[12] Smartphones use AI facial recognition, and car manufacturers use AI in their driver-assist features.

AI is being used in important areas of scientific discovery such as drug discovery and genomics[13] and across societal challenges such as climate change adaptation and mitigation.[14] In the UK, AI tools have been adopted by businesses in most sectors of the economy with varying levels of uptake and success.[15] Recently, leaders from across the UK’s political spectrum have called for AI technologies to be rapidly integrated into public-sector processes and services.[16]

At the same time, we are already seeing considerable harms caused by the misuse and failure of AI systems in different contexts. In healthcare, poorly tested and widely deployed AI systems have denied care to minoritised populations, failed to work accurately despite the manufacturer’s claims, and have reproduced racial biases.[17]

In the provision of public services, poorly designed AI systems have denied care to vulnerable communities, falsely accused people of being in debt and led to wrongful arrests and imprisonment.[18] In many cases, AI technologies can function well in one environment but break when deployed in another,[19] leading to unintended and harmful consequences.

These harms are not just confined to individuals: AI products and features can drive societal harms such as the spread of misinformation, exploitation, and oversurveillance of certain communities.[20] There is also growing evidence of AI systems being used to harass, intimidate and cause harm at mass scale. For example, a recent survey of 16,000 participants across 10 countries on the prevalence of synthetically-generated nude images found that 2.2% of those surveyed had personally experienced victimisation: more than double the rate of victimisation in the UK in 2024 for violent crime (1.3%), and nearly the same as sexual assault (2.6%).[21][22] A separate study found that 15% of the UK population had been exposed to harmful AI-generated deepfakes, which included nude images and misinformation.[23]

The modern AI sector is a highly resource-intensive and concentrated market, which can lead to undesirable environmental and economic impacts.[24] Training and running a cutting-edge AI system requires enormous levels of investment[25] and extracts significant ecological[26] and human[27] costs. As of 2022, data centres account for 1–1.2% of all global electricity usage and this number is increasing by 20–40% year-on-year.[28]

A small number of US technology companies control the majority of the compute and data infrastructure necessary to develop AI systems. This has led to open-source developers and academic labs becoming dependent on corporate-owned infrastructure[29] and caused new market entrants to be vulnerable to anti-competitive practices.[30] Some of these issues can be addressed by applying existing laws on competition, online safety and consumer protection. However, the UK lacks a joined-up regulatory approach to AI technologies that addresses the full range of risks they pose.

This is out of step with public expectations. In the UK, public opinion surveys routinely find that people expect AI regulation as a means of ensuring that these systems are transparent and accountable to human oversight.[31]

A nationally representative survey found that the establishment of an independent regulator was the most popular choice for AI governance among the British public.[32]

This regulatory gap in UK law has meant there are few requirements or incentives for developers or deployers of AI technologies in most sectors to ensure their systems are safe or effective before they are put into use.[33] As a consequence, the UK is one of many governments beginning to see AI regulation as a policy gap that needs to be filled.

To date, most national and local policy proposals for regulating AI, such as the EU’s AI Act, have followed ‘risk-based’ approaches that aim to reduce or prevent harms from the development and use of these systems without placing what are sometimes characterised as undue burdens on those developing and deploying these technologies.[34] Internationally, many jurisdictions believe that they will benefit from a competitive advantage if they can establish robust AI regulation earlier than their peers. As such, the race to regulate AI forms an important component[35] of what is increasingly seen as an AI ‘arms race’, whereby nations and blocs compete to deliver the economic fruits of AI.[36]

In various white papers over the last four years, the UK Government has chosen to adopt a non-statutory, principles-based sectoral approach to regulation. This approach would see existing regulators apply five cross-cutting principles (safety, security and robustness; appropriate transparency and explainability; fairness; accountability and governance; and contestability and redress) to AI technologies in their remit. This approach comes with no new statutory powers and some limited resource support for existing regulators. It also comes with the creation of a centralised risk monitoring function.[37]

The new Labour Government has announced it will legislate to create binding requirements on ‘those working to develop the most powerful artificial intelligence models’, but has stopped short of seeking to propose a more comprehensive AI bill.[38]

The regulatory challenge of AI

While regulating AI is now a well understood imperative for policymakers, it is not a straightforward one. As a technology area, AI poses several challenges for regulators:

- Complexity: ‘AI’ is a broad term that can refer to a standalone product, a feature of a product, a service sold to enterprise customers or a scientific research field. It covers a range of methods and use cases that depend on complex and geographically distributed supply chains. This means that it can be difficult to determine which actor in a supply chain for any given AI system is responsible for mitigating or preventing harmful outcomes.

- Unpredictability: AI systems can be deployed in a wide range of different contexts and sectors, with different use cases and in different configurations. The same AI system deployed in one context can have a drastically different performance from that system deployed in another. Generalising about the sorts of harms produced by AI systems in these different contexts can be challenging and can confound attempts to appropriately scope or target regulation.

- Dynamism: Even when consistently deployed in a specific context, AI systems can be dynamic. Their properties can change over time as models ‘learn’ from new data, are updated, or are used in unforeseen ways by human operators. This can make the behaviour and impacts of AI systems difficult to reliably predict in advance, challenging prescriptive approaches to regulation that specify how a product or service should function under a consistent set of circumstances.

- Opacity: The inner workings of AI systems can be difficult to describe or explain. Some AI systems are ‘black box’, meaning their computation can be so complex that it can be impossible to provide a clear explanation of how it reached a decision. AI system developers also routinely consider the training data or the design features of their products and services to be proprietary information and may refuse to share that information with the public, impacted communities or procurers of that product. Those experiencing harms, and the regulators tasked with investigating or enforcing them, won’t always have the information, access, or power they need to seek redress or prevent harm.

- Uncertainty: Compared to other technology sectors like pharmaceuticals, the AI sector is a nascent one with high levels of uncertainty regarding its potential importance to the UK economy. It is also not clear how AI products and services will benefit people and society. This means that calculating the trade-offs between the benefits and risks of regulatory interventions is difficult. There is a concern that regulation might stifle economically or societally beneficial forms of technological innovation.

However, these features are not unique to AI. Many of these challenges are shared in other domains that have been regulated, including the three that this paper explores. As policymakers seek to create new legal instruments, structures and institutions to regulate AI, they must first look to the lessons that can be learned from comparable sectors and technology areas.

A comparative approach

While AI brings its own unique complexities, it is not the first time that regulators have grappled with governing highly complex technologies that play a central societal and economic role. As we have explored in previous research,[39] there is no perfect analogy for AI, but looking at how other technologies and sectors are governed can help inform strategies for AI regulation.

In this paper, we look at three different areas of regulation and explore how these areas have been governed, aiming to provide a richer understanding of the benefits and drawbacks of different approaches. Our intention was to understand the ways in which different factors – from the design of regulatory institutions to wider sectoral economic conditions – practically impact the effectiveness of regulation.

We chose to look at three regulatory regimes, all in the UK context:

- Pharmaceuticals for human use

- Financial services (with a focus on consumer protection and the maintenance of financial stability)

- Climate change mitigation (specifically the carbon emissions regime established by the Climate Change Act 2008)

For each domain, we commissioned experts in that field to create a case study based on five research questions:

- What are the objectives of regulation in these different sectors? What should regulation seek to achieve?

- What mechanisms have regulators implemented in these different sectors to meet these objectives?

- How has regulation facilitated the creation of public benefit and how is this defined?

- How have liability and compliance burdens been distributed across the value chain in these sectors?

- How have any restrictions on access and proliferation impacted research and the size of the market?

Each case study drew on dozens of interviews with experts in those fields. For more details on our methodology, see ‘Methodology’ at the end of the report. More detail can also be found in each case study. [40] [41] [42]

Overview of selected regulatory regimes

In this chapter, we provide a brief overview of the objectives and structure of each regulatory domain.

Pharmaceuticals for human use

Regulatory objectives

Pharmaceutical regulation in the UK primarily aims to ensure that medicines used in the UK are effective, safe and of adequate manufacturing quality. As a secondary objective, regulators of pharmaceuticals are tasked with supporting an ‘enabling environment’ for the pharmaceutical industry which encourages innovation and positions the UK as a leader in health regulation in the international sphere.[43]

A pharmaceutical product receives authorisation to be sold on the market when regulators have deemed the medicine to be safe and effective. Regulators are under pressure to strike the right balance between ensuring confidence in the safety and effectiveness of a product and enabling the product to enter the market as soon as is possible. This is important for patients, who may benefit from accessing a new medicine, and industry, which wants to earn a return on their investment in developing the drug.

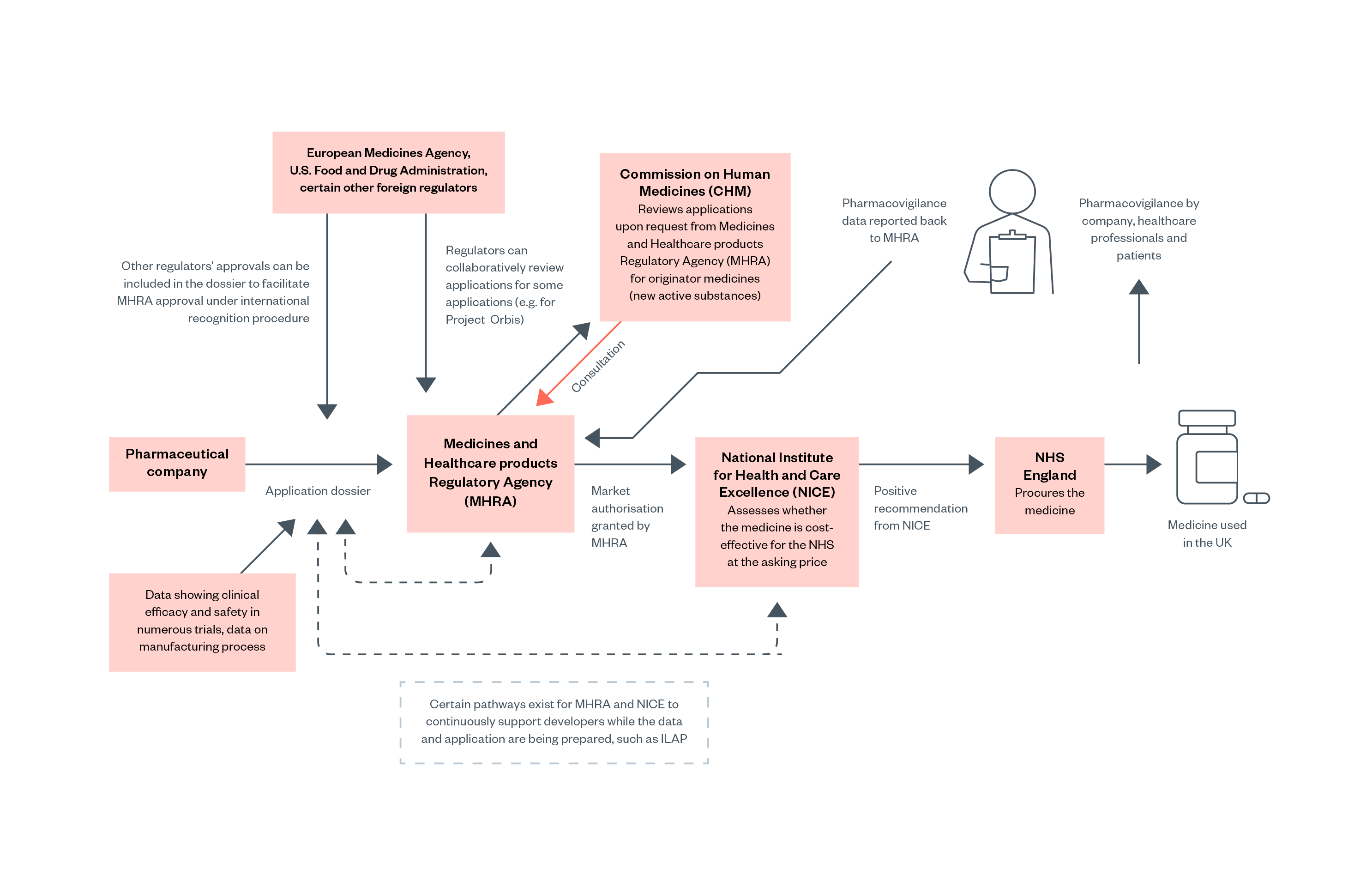

Pharmaceutical regulators

There are several UK regulatory bodies that are involved in the process of evaluating new pharmaceuticals, granting marketing authorisation, and evaluating their cost-effectiveness. The main regulator is the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which can make the decision to grant marketing authorisation if they believe the safety and efficacy of a drug are sufficiently proven.[44]

The MHRA is supported by the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM), an independent advisory body composed of medical experts. The MHRA will consult the CHM when handling complex applications, for example when a drug contains a new active substance. The CHM serves as a second review for drug applications deemed unsatisfactory by the MHRA.[45]

After the MHRA grants marketing authorisation, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evaluates whether the medicine should be reimbursed by NHS England. In some cases, a medicine is safe and effective, but not more so than an existing medication that is available at a lower price, in which case NICE may recommend against the NHS purchasing the medicine.[46]

Steps leading up to marketing authorisation

Applications for marketing authorisation are judged based on the new pharmaceutical’s performance in a series of clinical trials. Generally, pharmaceuticals undergo at least three phases of trials, starting with small trials to establish initial safety in healthy volunteers, and ending with trials to establish efficacy and broader safety across a large number of patients affected by the disease in question.[47]

Trials use different measures to define efficacy and safety, sometimes termed ‘endpoints’.[48] For example, in cancer drug studies, these can include the mortality rate, biochemical markers in blood tests or tumour size. In clinical trials, endpoints are used to show differences between a group of patients receiving the new medicine and a control group, as well as differences between patients with different demographic backgrounds. In general, a medicine will only move to the next phase of testing (for example, testing in a larger group of patients) if it has met certain pre-defined thresholds of efficacy and safety.

Some medicines can be authorised to enter the market earlier than others. If the medicine is equivalent to an existing drug in terms of active chemical substances (that is, a generic medicine), then the MHRA can grant approval without consulting the CHM. Medicines that have already been approved by trusted overseas regulators can also undergo a shorter review process with the MHRA.[49]

Some ‘innovative’ medicines are eligible to apply for an ‘accelerated pathway’ to marketing authorisation if they are likely to present a therapeutic advance and meet an unmet need, meaning that they are significantly different to medicines already in use.[50]

Figure 1: Overview of the process for pharmaceutical approval in the UK

Monitoring after entry

After a medicine is approved and released on the UK market, it is still subject to post-market monitoring, known as pharmacovigilance. In the UK, the MHRA has set up several schemes for reporting adverse drug reactions. The ‘Yellow Card Scheme’ is an online database that collates voluntary reports of adverse drug reactions from healthcare professionals and the public.[51]

Under the ‘Black Triangle Scheme’ medications are given ‘Black Triangle status’, indicated by a black triangle symbol on the packaging and information leaflet, when they are subject to ‘intense monitoring’. Black Triangle status is given to medicines that contain a novel active substance or have conditional approval and typically lasts for five years.[52] If sufficient adverse drug reactions are reported to be considered ‘disproportionate’ in the MHRA’s statistical analysis, then the MHRA can open an investigation and choose to revoke the marketing authorisation for the drug.

Financial services regulation

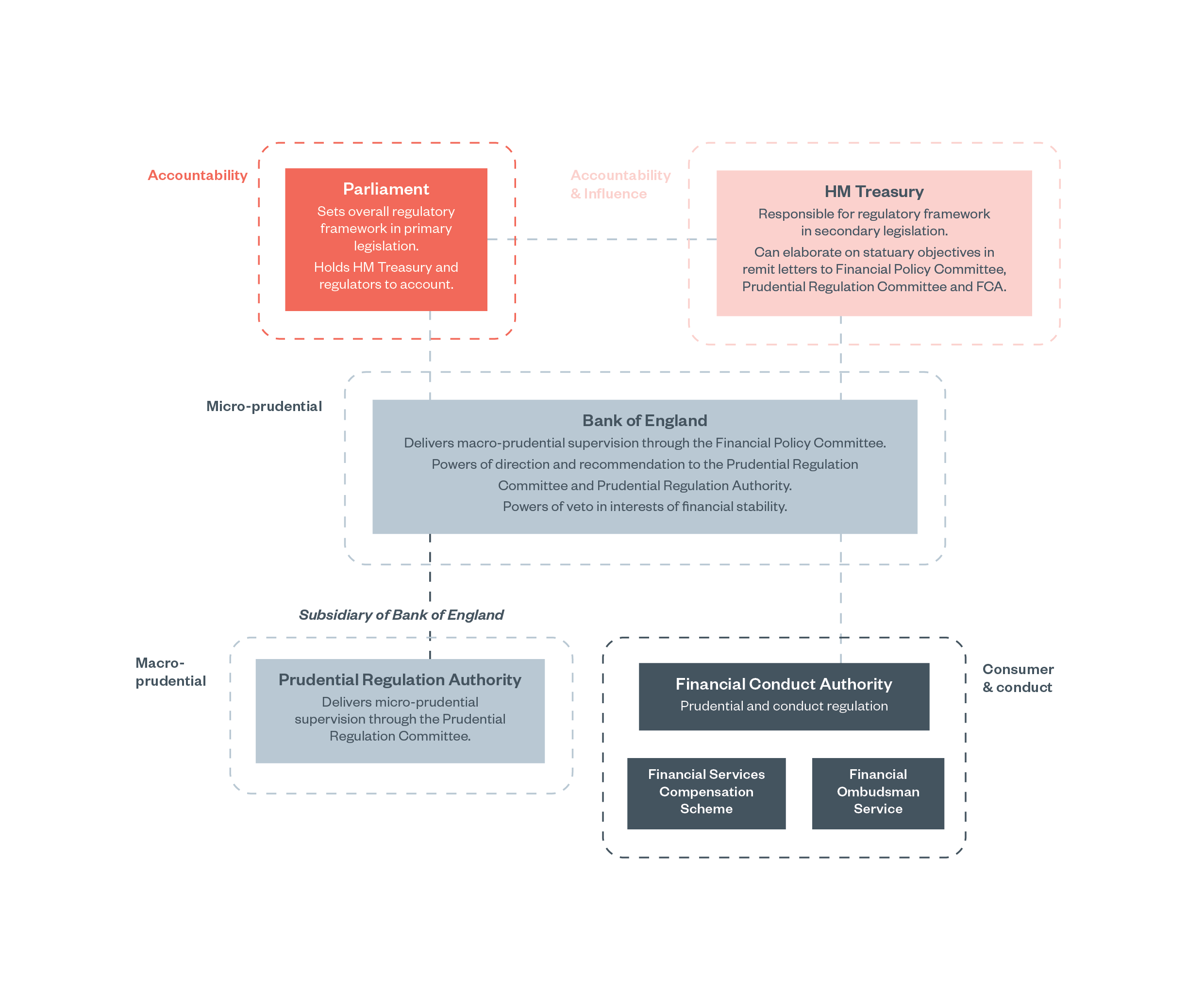

Regulators and regulatory objectives

Financial services regulation aims to regulate the behaviour of retail banks that offer services to households or businesses, wholesale and investment banks who engage in financial trading and advising, and other financial service providers. There are three main independent financial services regulators that carry out activities to address different objectives:

- The Bank of England (BoE)[53] aims to achieve price stability (limiting inflation) and maintain financial stability in the UK, which means that the UK financial system is stable enough to keep providing essential financial services even if the economy takes a downturn.[54] The BoE supervises several the critical financial market infrastructures (FMIs) such as payment, clearing and settlement systems which enable financial transactions in the economy and financial system to take place.[55]

- The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA)[56] sits within the BoE and its general objective to promote the safety and soundness of banks, building societies, credit unions, insurers and major investment companies in the UK.

- The Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA’s)[57] strategic (long-term) objective is to ensure that financial markets function well. Its operational (day-to-day) objective is to secure an appropriate degree of protection for consumers, protect and enhance the integrity of the UK financial system and promote effective competition between companies in the interests of consumers.

The PRA and FCA also have a secondary objective to support the UK’s economy and facilitate economic growth and competition. The BoE has a secondary objective about innovation in the provision of FMI services.

Figure 2: Overview of regulatory ecosystem for financial services

The regime for financial services regulation as it operates in the UK today was established in large part after the global financial crisis of 2007–8. In the aftermath of the crisis, the UK passed a series of legislative reforms intended to improve the overall safety and stability of the UK financial system by addressing the lack of resilience of individual banks and the lack of adequate consumer protection. Like the AI sector, risks in the financial sector can arise from the actions, conduct and behaviour of individual companies. Risks can also arise from cumulative actions across different companies or systemic ‘shocks’ to the entire sectoral ecosystem.

Systemic stability and resilience

The BoE is primarily concerned with macro-prudential regulation, which ensures that the financial system as a whole is stable and resilient. It does this by identifying, monitoring and mitigating systemic risks, which refers to risks to the stability of the UK’s overall financial system. Some of the main systemic risks considered by the BoE in 2023 include cyberattacks, geopolitical risks, climate risks and inflation risks.[58] The BoE’s Financial Policy Committee identifies, monitors and takes action to remove systemic risks to enhance the resilience of the UK financial system. The monitoring is done through mechanisms like the bi-annual Financial Stability Report, where the BoE tracks the views of market participants on risks within the UK financial system.[59]

The BoE also publishes an annual report on how it supervises the critical FMIs. It undertakes risk reviews and stress tests of the key FMIs and under new powers granted it can require FMIs to take, or refrain from, specific actions.[60] The Financial Policy Committee also has the power to mandate banks and financial institutions to take certain actions. For example, it can set capital requirements for banks or restrict the proportion of ‘risky mortgages’ that banks can take on.[61] It can give binding instructions and recommendations to the PRA and FCA. The Financial Policy Committee also monitors capital and liquidity positions by the UK financial sector as a whole by aggregating the capital and liquidity positions of individual financial institutions.

The BoE also conducts annual stress tests of the largest financial institutions. One example of a stress test is to design a hypothetical situation where multiple serious, yet realistic negative events occur simultaneously, contrary to normal economic conditions. The Financial Policy Committee then assesses if individual companies are sufficiently resilient to weather this scenario.[62]

If a financial service provider fails, the BoE is responsible for ensuring that this happens in an orderly way to prevent disruption to vital services and the financial market as a whole.

Safety and soundness of individual companies

The PRA and FCA deal primarily with micro-prudential regulation. This focuses on the safety and soundness of individual companies, safeguarding individual financial institutions from specific risks and preventing them from taking on too much risk. The PRA creates policies that companies must follow, such as the requirement to maintain sufficient capital and have adequate risk controls in place.

The FCA also regulates the conduct of individual companies. It does this by issuing rules, guidance and standards. An example of such a standard is the Consumer Duty, which requires financial services to put their customers’ needs first. The FCA has published guidance, including good practices, that companies should implement to meet their responsibilities under the Consumer Duty, such as training staff to recognise vulnerable consumers and provide additional support to them to ensure they receive a similar quality of service as non-vulnerable consumers.[63]

The FCA monitors if its rules are being followed with a combination of ex ante and ex post measures. These include enforcing an individual accountability regime for financial service employees and senior managers under which sanctions, including fines or revocation of an individual’s approval to carry out a senior management function, can be levied against employees and managers that fail to act in line with conduct rules. The FCA also monitors data shared by financial institutions for suspicious activity like market abuse or fraud. In 2000, Parliament set up the Financial Ombudsman Service where consumers can file complaints about a financial business for the FCA to investigate.

Additionally, the FCA also offers a range of services for companies developing new financial products, including regulatory sandboxes and support in navigating regulatory requirements. Regulatory sandboxes allow financial companies to test innovative products and services with a small number of consumers for a limited amount of time. Regulatory sandbox tests should have a clear objective, such as reducing costs to consumers. The FCA oversees the sandbox and provides support to ensure there are adequate consumer protection measures.

Climate change mitigation

Regulatory objectives

Carbon emissions regulation seeks to govern the individual actions of companies and institutions that are contributing to the collective harm of climate change. This regulation establishes a framework for setting economy-wide carbon budgets for the UK and seeks to foster cooperation from a wide range of actors in the public and private sectors to reduce their emissions to meet that budget.

The Climate Change Act 2008 (CCA) is the main body of law regulating carbon emissions reduction in the UK. The CCA and the related legislation and bodies provide an example of how companies across the economy can be steered towards a common goal. It seeks to measure and address society-wide impacts caused by the carbon emissions of a range of actors – such as farming practices, industrial manufacturing requirements and vehicle emissions standards. This echoes certain types of systemic risks posed by AI, such as the pollution of information ecosystems.

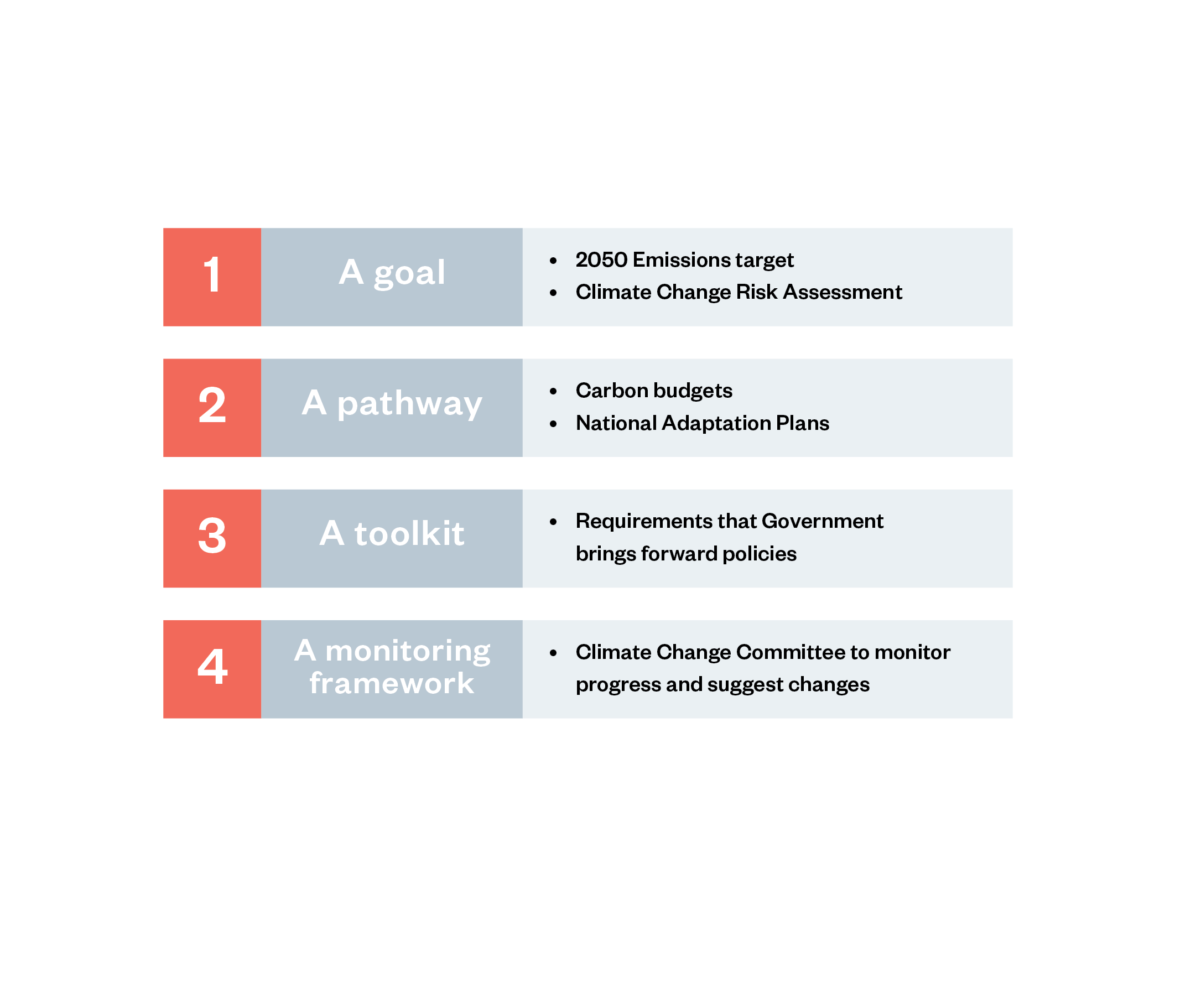

Regulatory mechanisms for mitigation and adaptation

The CCA creates several mechanisms for achieving its mitigation and adaptation objectives. Of most relevance are the statutory long-term emission budgets; a reporting body (the Climate Change Committee); ministerial powers to introduce regulations that discourage certain activities with high emissions; and the duty of the Government to report on progress to Parliament.[64]

Figure 3: The four pillars of the UK Climate Change Act[65]

The CCA initially set an emissions reduction target of 80% compared with 1990 levels by 2050, which was later amended to net zero (a reduction target of 100% compared with 1990 levels) by 2050 to align it with the 2015 Paris Agreement. These targets apply only to territorial emissions – emissions that occur within the UK’s borders – although the UK Government will start to include shipping and aviation emissions in its carbon budgets from 2033 onwards. The CCA mandates the Government to establish ‘carbon budgets’ for five-year periods, starting with 2008–12. These carbon budgets are formally set by the UK Parliament on the advice of the Climate Change Committee.

Regulatory actors

The Climate Change Committee is a statutory body made up of senior and expert academic climate scientists and researchers. Besides advising the Government on carbon budgets, it is also responsible for advising on long-term emissions targets and reporting progress on carbon budgets and the 2050 target.

Within the Government, currently the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero is responsible for climate mitigation policy. In addition to the CCA, the Government has adopted a combination of legislation (such as the Energy Acts 2008 and 2023) and non-statutory policies and strategies (such as the 2021 Net Zero Strategy) targeting economy-wide objectives and emissions reductions within different sectors, such as the energy sector.

Although the Government needs to report its progress back to Parliament, there is no formal sanction if the Government fails to achieve the objectives mandated in the CCA. Still, there is a legal duty to act, enshrined in the CCA, which allows citizens to pursue legal action against the Government if it can be deemed to be in breach of the Act.

Findings

In this chapter, we set out cross-cutting findings from our case studies that address the research questions in this report. These findings are split into three broad thematic areas:

- The establishment of regulatory regimes

- Regulatory institutions and their objectives

- Regulatory functions, which are further split into three broad areas:

- pre-market authorisation and conduct requirements

- post-market monitoring

- accountability, redress and enforcement

What follows is not an exhaustive description of these areas in relation to each of the three case study sectors – this can be found in the case studies themselves [66] [67] [68] – but rather a set of observations on common features across sectors that are relevant to policymakers working on AI regulation.

1. The establishment of regulatory regimes

The rapid and continuous development of AI technologies has led to claims[69] that it may be too soon to establish regulation or that more evidence on the capacity – and potential harms – of these systems is necessary before robust mechanisms are introduced.

Following the AI Safety Summit, hosted by the UK in Bletchley Park, Rishi Sunak claimed that the UK should not ‘rush to regulate’ and that we cannot ‘write laws that make sense for something we don’t yet fully understand’.[70] [71] Similarly a 2023 opinion piece from Microsoft’s Mustafa Suleyman and Google’s Eric Schmidt, co-signed by other tech leaders, suggested we need to first ‘address lawmakers’ basic lack of understanding about what AI is, how fast it is developing and where the most significant risks lie’ before countries pass national regulation.[72]

While these arguments have receded somewhat in recent months – with a new Labour Government in the UK signalling its intent to regulate powerful AI systems, and jurisdictions across the world bringing forward new regulatory proposals – they remain present in debates about AI governance.

Our research finds that gathering evidence often requires regulation – and so waiting for the necessary evidence to materialise before regulating is not an optimal approach. Mature regulatory regimes are not constructed perfectly overnight. Instead they emerge haphazardly, often after harm has occurred, and their functions develop and grow over time as a sector matures and its actors develop more consistent norms. There are never ideal circumstances or perfect off-the-shelf solutions. The history of existing regulatory regimes shows us that the most effective approach is to introduce capacities for monitoring and responding to risks that can then be flexibly iterated and strengthened as the sector changes.

A complex history of regulatory development

All three of our case studies illustrate that the development of regulation is not straightforward and linear. In the UK, pharmaceutical and financial services regulation developed in an uneven fashion as a consequence of public scandals that precipitated demands for policy change to maintain public trust.

The history of pharmaceutical regulation in western countries is a clear example of this, with high-profile product failures preceding the development of regulatory systems and expansions in regulatory power. Widespread sulphanilamide elixir poisoning in children in the 1930s led to the enactment of the US Food, Drugs and Cosmetics Act.[73] Most famously, the thalidomide scandal in the 1960s spurred the introduction of more rigorous drug testing – with explicit goals of safeguarding efficacy and safety – in the UK Medicines Act 1968, as well as in other jurisdictions across the globe.[74] The history of pharmaceutical regulation is one of pragmatic extension of regulatory power.

Similarly, significant parts of financial regulation came about in response to a public scandal. Financial regulation offers another example of haphazard regulatory development, with uneven swings between the extension and retrenchment of regulatory power. UK banks were subject to self-regulation and limited intervention until the Banking Act 1979, which put regulation on a statutory footing and made it an issue of UK Government policy.[75] While this supervisory regime was expanded in the Banking Act 1987, regulation remained light-touch until the aftermath of the 2007–8 financial crash.[76]

Pre-crash banking regulation was largely informal with limited state intervention and an emphasis on self-regulation. After the crash, new independent bodies were created with a focus on financial stability, the soundness of individual companies, financial market integrity, and consumer protection.[77] Banks were now subject to minimum capital requirements and stricter reporting duties[78] and their retail activities (focused on households and businesses) were separated from their investment sections, to protect the retail services from shocks in investment banking. Overall, these reforms increased accountability and consumer protection, and introduced measures to maintain stability within banks and the financial market as a whole.

Both of these histories – of pharmaceutical regulation changing and expanding in response to public scandal; and of the rebuilding of financial regulation after the 2007–8 global financial crisis – show regulatory institutions and objectives are not unalterable but can be reconstituted in response to changing evidence and periods of crisis.

The last few years have seen a growing number of public scandals due to AI systems causing societal harm. These have often involved AI being used in sectors that require high degrees of public trust, like public service delivery, education or law enforcement.[79] Without the creation of robust safeguards and accountability, the AI sector may see a decrease in adoption and innovation as consumers lose faith in these technologies and the institutions that use them. The evidence from other sectors suggests that policymakers ought to act pragmatically to expediate these measures to prevent harm, with the expectation of further iteration and reform as circumstances change.

Iterative and flexible governance

Although harms are already materialising in the AI space, regulation should not simply respond to past scandals but also be agile to adapt to, and prevent, future harms. Climate mitigation in the UK offers an important example of how governance can be designed from the outset to be iterative and flexible. The CCA was introduced as a comprehensive regime intended to prevent future harms from materialising, rather than a response to a previous scandal.

While the CCA can be seen as the first attempt in the UK – and one of the first in the world – to create a comprehensive national regime for monitoring and tracking carbon emissions, it did not create this regime from scratch. It built on and incorporated pre-existing regulatory infrastructures, including data gathering capacity and a dedicated regulator in the form of the Environment Agency, which focused on immediate and shorter-term environmental harms.[80]

However, besides setting up the Environment Agency, this pre-existing infrastructure consisted of non-binding policy that set emissions reduction targets for the Government. These non-binding targets proved ineffective in producing significant emissions reductions, and this was ground for the adoption of the legally binding CCA.[81] The CCA built on pre-existing policies, but was also born out of the realisation that these policies were insufficient to incentivise emissions reduction.

Regulating the AI sector might require adopting a similar approach that builds iteratively on existing structures and regulation. For example, existing UK competition and online safety policy may address some challenges for AI, but gaps may still exist that need to be addressed with a comprehensive piece of legislation and new institutions.

First, existing institutions should be empowered to act and react flexibly with regards to new developments, rather than having to wait for new legislation.

Second, the literature on climate policy suggests that the CCA was the product of particular political circumstances.[82] While it was a response to evidence that had mounted over decades, several experts have suggested that its introduction in 2008 was in many ways opportunistic. The suggestion is that the push for legislation was able to take advantage of a rare political consensus on the need for binding climate legislation across parties and devolved administrations with support from business representatives.[83] The AI sector finds itself in a similar situation, with growing international agreement and action on AI regulation.

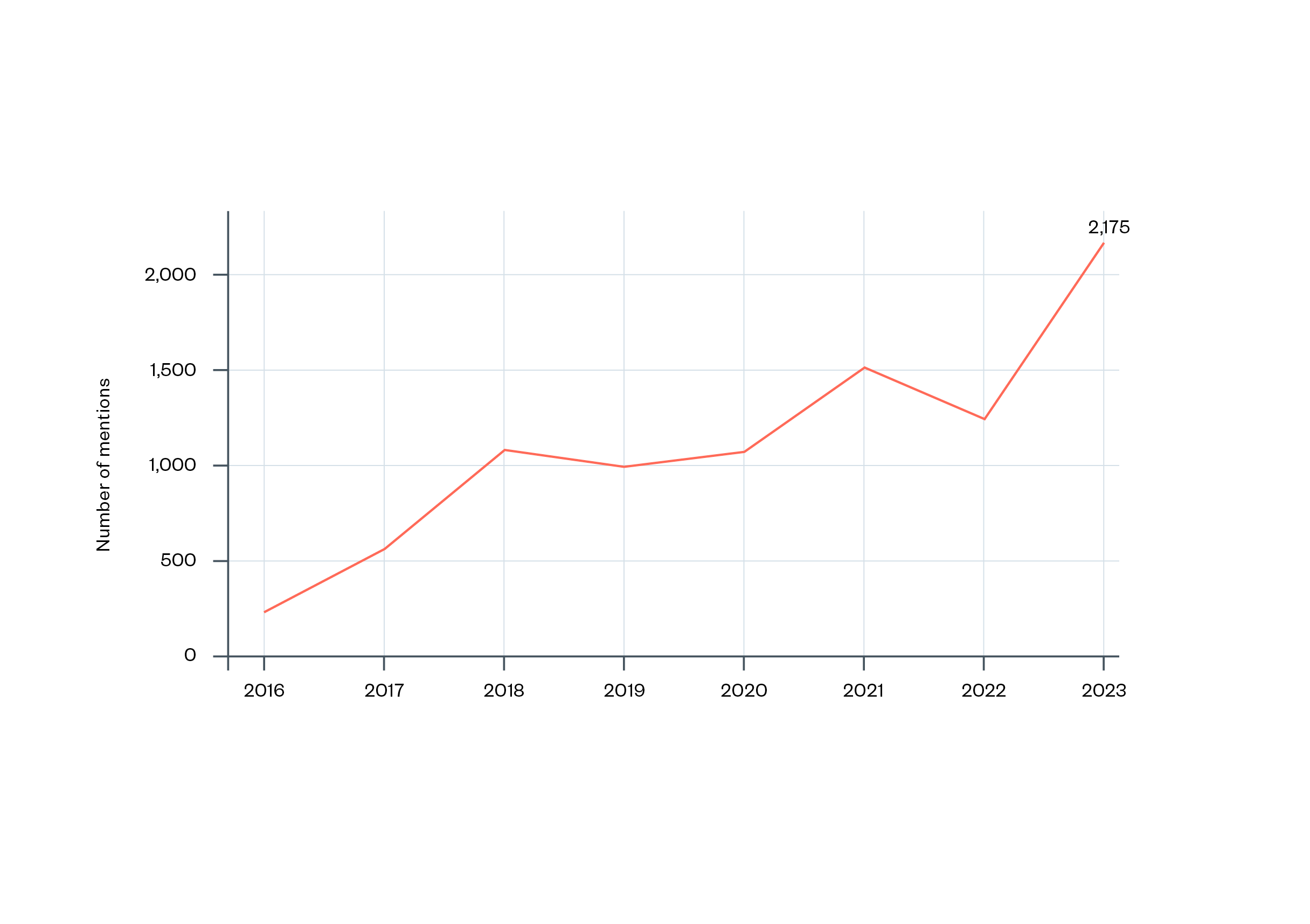

Figure 4: Number of mentions of AI in legislative proceedings in 80 countries, 2016–2023[84]

Third, the innovation of the CCA lies in its balance of flexibility and stability. It sets out high-level objectives, and establishes a monitoring infrastructure to track progress against these targets and shape Government and other policies over a long-term time horizon. As part of the monitoring infrastructure, the Government has a duty to regularly report to Parliament on its progress in meeting carbon budgets and the 2050 net zero target. Additionally, the Climate Change Committee publishes annual progress reports. Comparing emissions targets – set through carbon budgets and the net zero target – with emissions estimates, allows for progress against targets to be clearly reported.

The CCA’s framework is also responsive to changes in the evidence. Targets can be changed while retaining the overall framework, as has been done with the introduction of the more ambitious net zero target (the commitment to reduce emissions by 100% of 1990 levels, rather than the previous 80%) and the intention to incorporate shipping and aviation emissions. The Climate Change Committee plays an important role in this by monitoring progress and making recommendations for how the overall framework can be improved on and adapted. The CCA can therefore be seen as establishing targets, functions and regulation that would be built upon and would necessarily change and evolve over time.

As stated above, the CCA was passed in a period of considerable political consensus on climate, but that consensus has more recently broken down, placing pressure on the regulatory functions it established and altering their effectiveness. Regulatory regimes for AI will necessarily also be subject to fluctuations of this nature: the task is to create a regime resilient enough to maintain public confidence in technology throughout periods of change and political upheaval.

Regulatory regimes can also change over time in more subtle ways. Changes such as the UK’s departure from the EU and transformations in the political climate have influenced how regulatory oversight is exercised in practice. For example, after Brexit the MHRA has had to, in many cases, separate its regulatory processes from those of the European Medicines Agency.[85]

Regulatory leadership

The case studies also highlight how international dynamics can impact government motivation. On one hand, governments can be motivated to regulate early to establish regulatory leadership, as evidenced by the CCA. On the other hand, sometimes economic competition with other countries can lead governments to be slow to regulate, or even deregulate, with negative consequences for the stability of the sector (as shown by our case study on financial regulation).[86] Market size compared to other jurisdictions can also shape regulatory strategies and shape conditions for how countries such as the UK can exhibit regulatory leadership.

In some sectors the UK has been the first to enact global regulation, establishing a baseline for other countries. The CCA is widely acknowledged to be one of the first comprehensive framework laws on climate change and emissions, and an innovative example of legislation in its whole-economy approach to climate governance. [87]

A strong motivation for passing the CCA at the time was to establish the UK’s moral leadership on climate change, and thereby support global progress on emissions reduction by inspiring similar efforts in other jurisdictions. This approach has largely been successful: since its passage in 2008, several other countries have emulated features of the CCA, including France, Germany, Mexico and New Zealand. For years the UK was perceived as a global leader in climate, with its reputation diminishing in recent years as governments have failed to scale up climate efforts.[88]

Conversely, economic competition with other countries has also acted as a driver of deregulation at different times. In finance, the UK’s financial regulation witnessed a ‘race to the bottom’ in the 1960s to 1980s. Deregulation was motivated by a desire to make London the largest financial sector in the world. This did spur growth but ultimately undermined the stability of the sector in the long term as evidenced by multiple financial crises since the 1970s and 80s. Economic competition between countries does not intrinsically favour either regulation or deregulation; countries may seek a competitive edge through regulatory or deregulatory strategies at different times.

The size of national markets determines regulatory influence. Regulators in larger markets are more likely to set standards that will be followed by regulators in smaller jurisdictions. Pharmaceutical regulation gives us a clear example of this: approval decisions made by regulators operating in small- and medium-sized jurisdictions tend to follow the example set by regulators in larger jurisdictions (most notably the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the EU European Medicines Agency, which represent significantly more than half of the global market for originator medicines). There are therefore limits to the regulatory leadership that smaller jurisdictions can attain: the bar for approval set by regulators such as the FDA and European Medicines Agency sets an effective ‘floor’ for regulation, and reducing compliance requirements below this level is unlikely to create a significant pull factor for investment.

This is analogous to the AI sector. The UK is a relatively small AI services market compared to the USA and EU, the former of which is the home of the majority of big technology companies. However, both of these jurisdictions have begun to implement regulations aimed at governing AI systems. Several US states, including California, Colorado and New York, have proposed or passed regulation on various kinds of AI systems. The EU has recently passed its AI Act, which has established a regulatory baseline that many UK businesses building AI products will seek to comply with.

As these regulatory proposals are nascent, it is not yet possible to ascertain how well they will function. The proposals also contain several notable gaps. For example, none of these proposals address the risks of AI’s impact on displacing workers or adequately create requirements to assess the efficacy of AI systems. There is therefore still opportunity for the UK to exhibit regulatory leadership within these crucial aspects of AI regulation and have a significant voice in the global debate on AI regulation.

At the same time, considering the size of the UK market compared to the USA and EU, it is unlikely that there will be much benefit for the UK in setting out a framework for AI regulation that is significantly weaker than that set by its peers. Instead, the competitive advantage for the UK is likely to lie in factors that can support compliance and raise the bar for companies and consumers: for example, improved resourcing for regulators.

2. Regulatory institutions and objectives

A key challenge for regulators in the pharmaceutical, financial services and climate sectors is working constructively to shape the behaviour of large industry actors that often have considerable resources at their disposal. The sectors we investigated, primarily the financial services industry and the pharmaceutical industry, also grapple with having to regulate very large companies that in some instances are even considered ‘too big to fail’. The AI sector is also characterised by significant market concentration and is dominated by a small handful of large AI companies that provide the infrastructure and services for others to build from.

Through our research we have identified multiple factors that can aid in setting up (or undermining) a strong regulatory system that is able to manage such large market players. Key elements, discussed in the sections below, include ensuring the independence of the regulator from industry, government and other stakeholders; providing regulators with well-defined objectives; ensuring sufficient resourcing; and having multiple regulators with complementary responsibilities that can provide a system of checks and balances.

Independence and democratic accountability

In all three of the regulatory domains we investigated, regulators enjoy operational independence guaranteed by statute. Appointments of senior leaders in regulatory bodies are made by ministers, but regulators are routinely scrutinised by and ultimately accountable to Parliament. This structure is intended to safeguard against the aggressive pursuit of ideological or political agendas, while allowing for democratic input and scrutiny.

In recent years, these arrangements have come under threat. In financial regulation, an attempt to implement greater influence via a new ‘call-in’ power, was dropped following Parliamentary scrutiny. This ‘call-in’ power would have enabled the Treasury to make, amend or revoke regulators’ rules, thereby undermining their independence.

A softer form of accountability is the establishment of the Climate Change Committee, which reports on progress made by the Government against its emissions targets, and can therefore also show when the Government fails to meet its climate goals. As a body made up overwhelmingly of senior and expert academic climate scientists and researchers, the committee is highly trusted among civil servants and industry stakeholders. Yet experts interviewed for the case study agreed that the committee’s legitimacy could be enhanced by creating more channels for citizen and democratic participation in the development of policies to meet certain emissions targets. This could enhance public support for certain climate policies.

Resourcing

Historically, an essential aspect of functioning regulators has been the provision of sufficient resources, headcount and expertise to conduct research, assess for risk and enforce sanctions.

In the pharmaceutical context, adequate resourcing for existing regulators has been severely cut in recent years. The MHRA mostly relies on industry funding and has seen public contributions to its budget slashed in recent years.[89] This not only impacts the regulator‘s ability to carry out its objectives to a sufficient standard, but also makes the regulator vulnerable to pressure (both from pharmaceutical companies and other actors such as patient groups) to accelerate regulatory review in order to make a treatment available sooner. There is additional pressure to meet (or exceed) review timelines of regulators in other jurisdictions to keep a competitive advantage. According to our interview participants, this pressure may compromise public safety by allowing drugs to enter the market that have not been subject to the appropriate level of scrutiny.

Adequate resourcing is also essential to avoid ‘industry capture’ which can occur when regulators serve the interests of the industry they are tasked with regulating, rather than acting in the public interest. Underfunding creates challenges in terms of providing adequate staffing to meet deadlines and allow for a smooth regulatory process. This can create a ‘revolving door’ between regulators and industry, with regulators struggling to retain staff in the face of attractive industry pay packages.[90] According to some of our interview participants, this risks creating overly close relationships between regulators and the industries they are tasked with regulating.

The AI sector contains several similar challenges, with many regulators lacking the resources, expertise and capacity to effectively address the challenges posed by AI systems. While the UK Government has launched a £10m fund for regulators to apply for temporary funding to help them address these challenges, this type of limited funding approach may not address the core issues of capacity and resourcing.

Tackling the problems created by underfunding – and ensuring that regulators are adequately resourced to tackle challenges in their sectors – requires more funding through public spending or industry levies. In the sectors we examined, the dominant funding models are user fees (pharmaceuticals) and levies on parts of the sector (finance). The operation of the Climate Change Committee is funded through general taxation, although it is worth noting that levies do exist for specific green policies.

Generally speaking, levies are seen an important tool for creating ring-fenced budgets for important public interventions, while placing the burden for financing on the sectors who benefit the most from those government interventions. It is worth noting, however, that there are drawbacks to these funding models. Some interview participants claimed that industry fees in particular afford regulated companies leverage over regulators that they would not otherwise have.

Objectives

The debate over AI regulation often includes suggestions that regulators should not simply work to prevent harms from AI, but should also work to promote the uptake and innovative use of these systems. This reflects a broader trend in public policy, seen across multiple sectors, to introduce secondary objectives for regulators.

In the domains we studied, this trend has achieved mixed success at best. Secondary objectives – such as ‘creating an enabling environment for the pharmaceutical industry’ (MHRA) or ‘facilitating international competitiveness and growth’ (FCA and PRA) – may conflict with one another and with core regulatory goals, such as ensuring drug safety or consumer protection. This risks compromising the effectiveness of important regulatory functions and opening the door to the politicisation of regulatory activities.

In UK pharmaceuticals regulation, the MHRA is the agency tasked with a primary objective of ensuring that medicines used in the UK are ‘effective, safe, and of adequate manufacturing quality’.[91] However, the MHRA also has secondary objectives: ensuring an enabling environment for the pharmaceutical industry, encouraging innovation, and positioning the UK as a leader in health regulation in the international sphere.[92] The FCA is charged with similarly wide-ranging objectives: from ensuring market stability and consumer safety to promoting economic growth.

Some of these secondary objectives have been introduced in the last few years. The Medicines and Medical Devices Act 2021 (MMDA) makes explicit the regulatory objective of creating a favourable environment for industry, including, implicitly, for foreign companies or investors. At the time the introduction of this objective was seen as controversial within academia and civil society, with experts warning that it could undermine safety considerations.[93] Interviewees suggested that this new secondary objective had been introduced in response to an acceleration of competition between regulators in different countries in creating favourable conditions for companies.

In addition to contention at the level of politics and statute, these secondary objectives around creating a favourable industry environment can also create elements of uncertainty in the technical practices of regulators, particularly when these practices include some measure of subjectivity or social value judgement. For example, NICE makes judgements on the cost effectiveness of medication based on Quality-Adjusted Life Years. A Quality-Adjusted Life Year measures the effect of a drug or medical device’s effect on a patient’s combined quantity and quality of life. This methodology includes ‘social value judgements’ made by the regulator, based, where possible, on data on patient-reported preferences and quality of life.[94] These judgements in turn are influenced by the regulator’s objectives making the prioritisation of competing regulatory objectives an important factor in the determination of cost effectiveness.[95]

One way in which policymakers have attempted to resolve this uncertainty is to have a clear hierarchy of objectives. This is the case in financial services whereby secondary objectives, regulatory principles and remit letters sit in descending order under the FCA and PRA’s primary objectives. The regulator judges on a case-by-case basis which principles are relevant and should influence the outcome of a decision, besides its primary objectives, which leaves some room for discretion by the regulator.

The choice of whether to prioritise one objective over another can favour the interests of different stakeholders (such as pharmaceutical developers, the health service and patients themselves). Pressure to promote economic growth and create a favourable environment for business can push regulators to favour industry interests over patient safety in some cases.

Some experts have claimed that the introduction of growth objectives has led to the MHRA focusing more on pharmaceutical industry needs over patient safety, especially in the context of accelerated pathways.[96] Similar concerns have been raised in the financial sector, where the new secondary objective in 2023 for the PRA and FCA to promote international competitiveness of the sector creates a perceived conflict of interest for regulators who are now required to both regulate and promote the financial services sector.

In the case of pharmaceutical regulation the evidence for the effectiveness of pro-innovation regulatory measures is limited at best. Two-thirds of drugs that undergo expedited or accelerated approval review generally fail to perform better than available alternatives and exhibit a higher rate of safety events and withdrawals from market.[97] The evidence from pharmaceuticals gathered from our interviewees and roundtable participants is therefore that introducing secondary objectives around innovation and competitiveness can be counterproductive, compromising safety efforts without yielding significant public benefit.

Checks and balances

To help mitigate the risk of institutions becoming ‘captured’ by particular interests, some mature regulatory regimes include an ecosystem of independent institutions that can hold each other accountable and act as effective checks and balances.

In pharmaceuticals, the MHRA’s regulatory functions are complemented by those of NICE, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the CHM.[98] These organisations act as checks on each other: for example, the CHM is consulted by NICE on novel medicines and also acts as an authority for appeals when medicines are not approved by the MHRA.[99]

While these bodies are all part of a unified ecosystem, acting towards shared aims, each has its own objectives and can act independently of the others. For example, a medicine approved by the MHRA does not need to be approved for purchase on the NHS by NICE. This distribution of power and accountability helps to ensure the resilience and integrity of the overall system even when individual parts are vulnerable to pressure from external stakeholders.

Conversely, in financial services, while the presence of multiple specialised institutions has also been seen as a strength, it has at times posed problems related to oversight and coordination, and claims have been made that smaller and more specialised institutions are more vulnerable to regulatory capture. The regulatory landscape consists of multiple big regulators (BoE, PRA, FCA), but also some smaller regulatory bodies looking at specific elements of the financial sector (for example, the Payment Systems Regulator, and the Pensions Regulator). Banks can also be impacted by big tech companies who provide cloud services. Having such a decentralised regulatory system potentially causes issues for coordination between regulators and oversight of the sector as a whole.

The wider regulatory ecosystem

Beyond the core of regulatory institutions, wider stakeholders in civil society and academia also play an important role in the regulatory ecosystem of the three sectors we looked at. These actors support activities such as critically assessing regulatory methods and advocate on behalf of affected persons.

For example, in the financial sector certain designated consumer bodies can take action as super complainants on behalf of affected groups.[100] Stakeholders in civil society and academia also provide valuable independent validation and critique of regulatory practices.

Despite this, our interview participants in all three case studies noted that private interests tend to have an outsized influence compared to civil society or academic stakeholders within the regulatory process.

In recent years, both financial and pharmaceutical regulation in the UK have exhibited a trend towards institutionalising the involvement of affected persons as a counterbalance. In finance, the establishment of the Financial Services Consumer Panel, the Practitioner Panel, and the Small Business Practitioner Panel, aims to ensure broader input into the work of regulators beyond the traditional mechanisms of consultations and calls for input. In pharmaceuticals, changes have been introduced to ensure that two patient representatives are included in every decision-making committee.

Our research found some optimism about the potential of these reforms to ensure regulation operates in a more inclusive way that is responsive to the needs of a wide range of stakeholders,[101] although it was also suggested that the success or otherwise of these reforms cannot yet be fully assessed.

Similar initiatives would be well suited for AI regulation, although current UK proposals have not sought to create methods for citizen or independent expert oversight or engagement in decisions around how to regulate and deploy AI systems. While there is a drive to improve AI expertise within the Government and sectoral regulators, there are no independent public institutions with AI governance at the heart of their remit. The evidence from other regulatory regimes suggests that this is a significant gap, leaving the development of AI governance subject to ministerial whim, political churn and other regulatory priorities.

3. Regulatory functions

Ex ante and ex post mechanisms are often proposed in AI regulation debates as different approaches to tackling harm. Our research suggests that effective regulation utilises both to ensure documentation and harm mitigation throughout the lifecycle of a service or product, including after it has been released.

The aim of regulation in the three sectors discussed in this report is generally to prevent harms from occurring. Still, as discussed in earlier sections on the emergence of regulatory regimes, harms or policy failures occur even when regulation is in place.

For this reason, it is common to have accountability and redress mechanisms in place. Accountability here means that actors can be held responsible for failing to adhere to or enforce regulation via investigation and/or enforcement of sanctions by a competent body. Redress ensures that that potential victims have a viable route to raise complaints and seek remedies. All three of the regulatory systems in this report have implemented methods for accountability and redress, albeit in diverging ways.

Steps required for marketing authorisation and conduct requirements

Both financial regulation and pharmaceutical regulation in the UK place strong market entry requirements on financial companies and pharmaceutical products, respectively.

In finance, companies and their business models need to be authorised by the regulator. This means that the company applying for authorisation must show how the company will be governed, the kinds of activities it intends to undertake and how it intends to ensure that these activities will comply with regulatory principles such as the Consumer Duty.[102] Additionally, senior employees must meet a ‘fit and proper’ test, which assesses evidence of the prospective employee’s honesty, integrity, competences, capability and financial soundness.[103] The PRA’s Threshold Conditions, which include having appropriate resources to manage risk and ‘fit and proper’ governance arrangements must also be met at all times before being allowed to carry out regulated activities.[104]

In pharmaceutical regulation, all medicines placed on the market in the UK require marketing authorisation which serves as the main point of leverage for regulators. Marketing authorisation is received when a product is deemed safe and effective based on evidence collected in clinical trials that measure how well the drug performs in terms of certain ‘endpoints’. For example, for a cancer drug, these endpoints could include survival rates after a certain period or changes in tumour size. This whole process of evidence gathering goes through multiple stages and takes several years. Some legal experts have argued that ‘the decision to approve a medicine effectively signals an end to the gathering of meaningful and reliable information as to safety’,[105] pointing to concerns that while post-market monitoring measures exist in pharmaceutical regulation, they are very limited, as will be discussed in the section below.

The effectiveness of market entry requirements is shaped by several sector-specific factors, but two factors featured across our case studies.

First, the presence of robust metrics is key in pharmaceutical regulation, financial regulation and carbon emissions regulation. Such metrics should be set independently – by regulators or an independent third party – rather than by the regulated entity. This prevents pre-market assessments from being ‘gamed’ and builds trust by allowing external entities (for example, academics, auditors and the general public) to verify the results of compliance activities.

In pharmaceutical regulation, regulators publish guidance on recommended endpoints that can be used as metrics in clinical trials and against which applications for marketing authorisation for new drugs are judged. Under the CCA, the five-year carbon budgets are formally set by the UK Parliament but under the advice of the independent Climate Change Committee. In financial regulation, banks receive ‘authorisation’ to operate on the UK market if they are deemed ‘sound’. One way in which this is measured is by determining if the bank has sufficient liquid assets. The Financial Policy Committee, which sits in the BoE, sets the liquidity requirement and when they think risks to financial stability are growing, they will require banks to maintain more liquid assets.

In these cases, there is a strong role for regulators to set requirements for what counts as valid evidence of good practice; regulated companies should not ‘mark their own homework’. Companies do in many cases have input into regulatory standards, which can include (in pharmaceuticals) collaborating with regulators to develop clinical trial endpoints. For pharmaceuticals, academics and practitioners (for example doctors) play a key role, by undertaking research to look at long-term drug safety (this research is often undertaken ad hoc, based on individual researcher’s initiatives, rather than in an organised framework). While this is a key process for keeping regulatory standards workable and up-to-date, regulators have the ultimate say in whether a product can enter the market and this ensures that public interest considerations are centred in negotiations.

Second, economic incentives and business models also shape compliance with market entry requirements. In pharmaceuticals, for example, decisions by companies about whether or not to take the development of a drug forward are conditioned by profit considerations, which are in turn shaped by the nature of the funding available to a company and the price that it can hope to charge for the drug once it reaches the market. Often these incentives are not aligned with the aims of regulation – making the job of the regulator harder and exposing them to political pressure.[106] Interviewees and roundtable participants in our project indicated the consequent need to ensure that economic considerations (such as market structure and prevailing business models) are considered as levers affecting company behaviour, alongside regulatory requirements, rather than as a separate or siloed policy area.

It is also worth considering how market entry requirements can contribute to market concentration by placing high burdens on new market entrants. For example, in pharmaceuticals, regulated companies need significant resources and expertise to comply with regulatory requirements such as the obligation to carry out clinical trials. Coupled with non-regulatory factors like the need for high up-front, at-risk investments to develop new drugs, this creates barriers for new drug developers wishing to enter the sector.[107] As a result, smaller drug developers will commonly sell their intellectual property to large pharmaceutical companies that are better equipped to comply. In other cases the entire company may be acquired early in the drug development process.[108]

In the context of AI, legislators should consider how regulation will impact on market concentration and might impact on market entry by newcomers.

Monitoring

Monitoring was highlighted as a key challenge by experts in the sectors we explored. The three sectors referred to in this paper monitor for different things. Within pharmaceuticals, monitoring mechanisms aim to identify for harmful incidents or further information on whether a drug works as intended. Within financial regulation, monitoring focuses on assessing the stability of financial markets and on the continued stability and soundness of financial institutions. Within carbon emissions regulation, monitoring is used to see how the Government performs against its emissions reduction goals.

Post-marketing requirements in the pharmaceutical sector are not always complied with. A significant proportion of medicines are approved ‘conditionally’, meaning that companies are required to undertake additional studies on certain aspects of the medicine (generally safety) as a condition of approval. While data on UK-specific compliance with such requirements are not available, a study of European Medicines Agency cancer medicine approvals found that 47% of post-marketing requirements were not completed on time.[109]

Similarly, voluntary reporting of harmful incidents through the ‘Yellow Card Scheme’ is weak, challenging efforts at comprehensive monitoring. In the UK it is estimated that around 90% of adverse drug reactions go unreported.[110] There have been cases in which it was alleged that manufacturers have withheld concerning safety data from regulators, including for rofecoxib (an arthritis medicine) and paroxetine (an antidepressant).[111]

In the UK, companies are primarily responsible for pharmacoviligence, whereas in the USA, by contrast, the FDA takes a more active role in monitoring safety incidents.[112]

Climate and finance regulation bring into focus the question of monitoring systemic risks, a key challenge in AI. The Climate Change Committee collates evidence on performance against climate targets which are set nationally in alignment with international standards, such as the 2050 net zero goal. This progress is measured through estimates of territorial emissions which include the decrease in emissions compared to 1990 levels from UK-based businesses, activities of people living in the UK and land, including forests and crop or grazing land. The UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero collects this data and must regularly report on its progress to the UK Parliament. Also, the Climate Change Committee reports annually on the Government’s progress. When the progress is insufficient this means that the Government must take extra measures to meet its targets.