Delegation Nation

Advanced AI Assistants and why they matter

4 February 2025

Reading time: 43 minutes

Key insights

- Recent improvements in the performance and reliability of foundation models are leading to the development of applications that we call Advanced AI Assistants: systems that are able to engage in fluid, natural-language conversation with users and that are designed to play particular roles in guiding and taking action for users.

- Advanced AI Assistants can come in various forms:

- executors, like Open AI’s ‘Operator’,[1] which take action directly on the world on a user’s behalf

- advisers, like legal instruction bot DoNotPay,[2] which set out the specific steps a user needs to take to accomplish a particular goal

- interlocutors, like the mental health app Wysa,[3] which aim to bring about a particular change in a user’s mental state.

- Advanced AI Assistants are typically easy to use, highly personalised and personable, and well suited to carrying out complex, open-ended tasks. As such, they could:

- be used by the general public more and for more kinds of tasks than any earlier kinds of AI assistants

- prompt a dramatic increase in the number and variety of decisions and tasks the average person delegates to AI

- exert considerable influence over users’ mental and emotional states.

- The implications of the rise of Advanced AI Assistants could therefore be profound. The proliferation of these systems makes longstanding policy and legal questions around AI safety, bias, liability and privacy more complex and more urgent.

- Advanced AI Assistants pose especially difficult questions about the concentration of market and political power and about the psychological impact of people’s relationship to AI.

- Given Advanced AI Assistants’ potential influence over user thought and behaviour – as well as the amount of data they collect on users – their integration into our economic and personal lives could place an unprecedented amount of power in the hands of the small number of large companies developing, providing and controlling these systems.

- Advanced AI Assistants could also have a significant impact on individual users’ wellbeing, potentially leading to risks of greater emotional and practical dependency on AI systems.

- For these reasons, policymakers need to devote special attention to Advanced AI Assistants. To adequately account for (and ultimately address) the impacts of and challenges posed by Advanced AI Assistants, policymakers must:

- Look beyond safety and performance considerations. Discussions about the implications of Advanced AI Assistants should not be limited to the consequences of these applications failing, or performing poorly at a technical level, but should also include their potential political and economic implications. The possible impacts of the use of Advanced AI Assistants on market competition and democratic debate will be especially important to consider.

- Explicitly consider the impacts of Advanced AI Assistants that act on the world indirectly. Much of the current debate on Advanced AI Assistants focuses on systems able to take action on the world directly, sometimes referred to as AI agents. Policymakers also need to attend to the significant impact of Advanced AI Assistants that act on the world indirectly, either by guiding human decision making by taking on roles traditionally held by human ‘advisers’, or by acting to influence the mental states of human users in ways that are far more personalised and convincing than previous systems.

- The Ada Lovelace Institute will be working on this topic in more detail, with the aim of providing evidence-based analysis of the current state of play, the extent and adequacy of existing regulatory and legal protections, informed public views and concrete recommendations for policymakers.

Introduction

Of all the depictions of AI in popular culture, perhaps one of the most enduring is that of the AI assistant. Visions of computerised interlocutors – capable of engaging a human in a natural conversation, providing information and advice, and carrying out complex tasks with a high degree of independence – have been staples of science fiction for decades.[4]

Until relatively recently, the technological capabilities required to create systems with these assistant-like features had proven elusive. The closest approximations were virtual assistants like early versions of Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa: applications capable of recognising, responding to and acting on specific kinds of oral and written user prompts, but limited to stilted exchanges and unable to tackle more idiosyncratic or complex requests and questions.

Within the past few years, however, this has started to change. With the development of foundation models, AI systems have become increasingly capable of producing convincing, sophisticated natural language, and – more recently – increasingly able to carry out complex, open-ended tasks. For instance, Operator by Open AI[5] and Claude 3.5 Sonnet Model by Anthropic[6] can both access a web browser to carry out tasks requiring several distinct, intermediate steps in response to a written user prompt.

One of many implications of these advances is that, together, they enable the creation of AI assistants with far more advanced capabilities than their predecessors. Foundation models can be modified to create applications that can engage in fluid, natural-language conversations with a human user; interpret, learn and remember a user’s preferences and goals; and address more complex, open-ended tasks.[7]

These kinds of applications, which we call Advanced AI Assistants, are the subject of this briefing paper.

Advanced AI Assistants are being vigorously championed by the tech industry,[8] and are increasingly being cited as the future ‘killer app’ that could make the use of generative AI mainstream and indispensable.[9] Suggested roles for Advanced AI Assistants range from mental health therapy, coaching and education, through to the provision of expert advice and the automation of difficult, boring or onerous tasks. Given these proposed uses, claims have been made about the ability of these systems to supercharge productivity[10] and democratise access to expertise and assistance otherwise provided by humans.[11] [12]

A large part of the appeal of Advanced AI Assistants is that they are both very easy (and sometimes enjoyable) to use, and capable of taking or guiding reasonably complex action on behalf of a user. Getting an Advanced AI Assistant to reorganise your diary, respond to your emails, or find and book you a hotel according to specific criteria can be as simple as speaking or typing the initial request, and answering a few clarifying questions.

As a result of this combination of features, Advanced AI Assistants could prove easy to fit into people’s existing routines and workflows, leading to a substantial increase in the number of people using AI in their everyday lives for non-trivial tasks.

In a best-case scenario, Advanced AI Assistants could profoundly widen access to a transformative technology, enabling people with no special digital skills to automate work and to access ‘professional’ advice or support that may have otherwise been out of reach.

At the same time, the very features that make Advanced AI Assistants so appealing pose deep policy challenges. Precisely because they are designed to feel easy, fun and useful, Advanced AI Assistants are a technology that could have a high degree of influence over how people act on and relate to the world. Advanced AI Assistants’ personalisation and use of natural language can make them very charming and persuasive, and could encourage a more passive, trusting approach to interacting with digital technology.

Advanced AI Assistants could therefore hold considerable power to affect users’ thinking and mood. Moreover, although they are designed to help realise user specified goals, Advanced AI Assistants’ use of fluid natural language gives them the ability to use clarifying questions to nudge users towards different objectives (including, potentially, those of favoured by the developer of the system). Similarly, Advanced AI Assistants’ applicability to more complex tasks can give them a degree of discretion over how those goals are realised.

The amount of sway Advanced AI Assistants could hold over users poses two challenges in particular.

First, Advanced AI Assistants could cause real psychological and material harm to individual users. Accounts of user interactions with less sophisticated AI Assistants demonstrate the potential for people to develop unhealthy emotional dependencies on these kinds of systems, and to trust misleading or dangerous advice and suggestions generated by them.[13] [14] As Advanced AI Assistants have the potential to be far more convincing, and to be used far more widely than their predecessors, these risks could well be more severe.

Second, Advanced AI Assistants present difficult questions about economic and political openness and competition – especially in the context of current market dynamics, in which Advanced AI Assistants are being developed and offered to consumers by a handful of large tech companies.

Some have predicted that Advanced AI Assistants may become the principal way most people interact with AI and digital information.[15] If this happens, AI developers will have not only the power to pre-determine an Advanced AI Assistant’s behavioural dispositions, but also – by extension – the power to determine what information and ideas users are and are not presented with, how choices and different options are framed, and what kinds of tasks people can automate, and in what way.

Likewise, should Advanced AI Assistants become indispensable tools in people’s working and personal lives, the companies providing access could have considerable scope to extract high rents from end users and set terms of access (such as sharing of personal data) that would be difficult to contest. In the absence of countervailing forces, Advanced AI Assistants could bring about an considerable expansion and consolidation of the tech industry’s political, economic and soft power.

This briefing paper provides a primer for policymakers starting to think about the implications of Advanced AI Assistants, and how these should be approached. It sets out our definition of these applications, and articulates how they work and how they differ at a technical level from other forms of AI. It provides an overview of some of the biggest, most urgent policy questions and challenges posed by their development and proliferation, and sets out our own plans for work on this topic.

Note on methodology: this briefing paper is informed by interviews with ten external experts and by desk research conducted in autumn 2024.

What is an Advanced AI Assistant?

We define an Advanced AI Assistant as an AI application, powered by a foundation model, that primarily uses a natural-language interface, and that is capable of and designed to play a particular role in relation to a user.

Roles of Advanced AI Assistants

Advanced AI Assistants are designed to take on one (or more) of the following roles in relation to a user:

- an executor, acting directly on the world on behalf of a user

- an adviser, instructing a user on how to accomplish a particular task or realise a particular objective

- an interlocutor, interacting with a user to bring about a particular mental state.

Natural-language interface

The main way that a user communicates with an Advanced AI Assistant is via natural language (such as text or speech). Advanced AI Assistants may, in some cases, use other informational inputs to inform and supplement their interpretation of users’ goals and requests (such as biometric data to infer a user’s emotional state). They may also use other modalities, such as pictures and diagrams, to present information to users. However, these inputs and modalities will be in addition to their use of natural language.

Personalisation

Advanced AI Assistants are capable of learning and factoring in the preferences, needs and dispositions of a user, becoming more personalised to a user over time.[16]

Related terms and concepts

The concept of an Advanced AI Assistant, as set out above, is related to but distinct from the following commonly used terms.

- AI agents: AI systems that ‘have the ability to act upon and perceive the environment in a goal-directed and autonomous way’.[17] While many Advanced AI Assistants (such as those that play the executor role) count as AI agents, not all will. Conversely, not all AI agents count as Advanced AI Assistants – by virtue of lacking a natural language interface or a sufficiently high degree of personalisation.

- AI assistants: Any AI systems designed to stand in a particular relationship to a user (as an adviser, interlocutor or executor). These systems can be but are not necessarily powered by foundation models, can display lower levels of personalisation and can be less suited to complex or open-ended tasks than their advanced counterparts. Both Advanced AI Assistants and virtual assistants count as AI assistants.

- Virtual assistants: AI assistants not powered by foundation models, but that instead use rule-based reasoning. Early forms of Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa count as virtual assistants.

How do Advanced AI Assistants work?

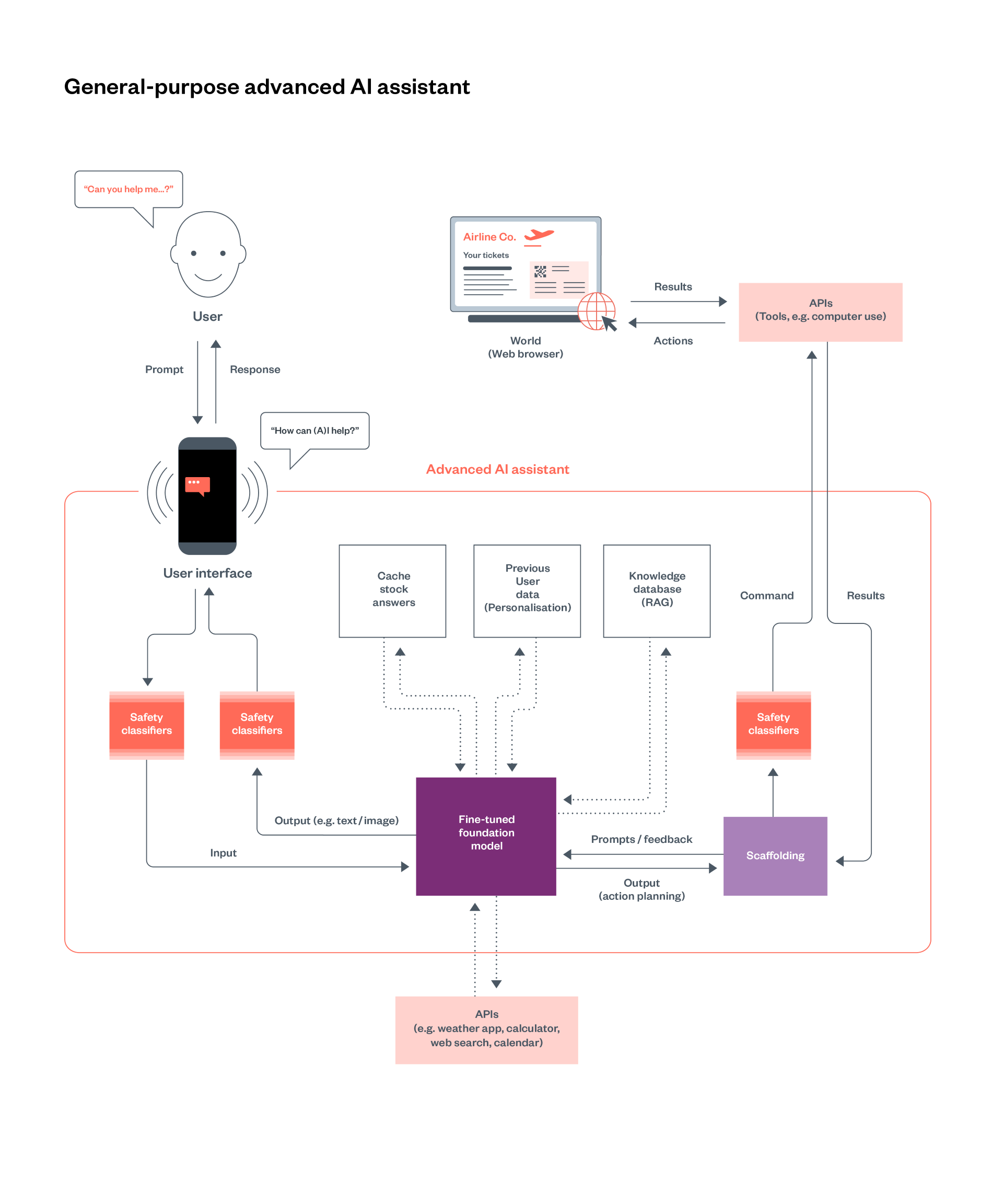

This section sets out the components and methods used to create Advanced AI Assistants – as shown in the diagram above – and how these differ from earlier virtual assistants. We recommend this section for readers who want to understand the technical features of Advanced AI Assistants in more detail. See the next section for a survey of the challenges and questions posed by Advanced AI Assistants.

This diagram shows the workings of a generic Advanced AI Assistant and how it interacts with the world. The boxes show the different components of the Advanced AI Assistant, and the arrows show how information is passed between them. The dotted arrows show where the foundation model may access additional resources to generate answers that are more accurate, personalised or less resource-intensive. This diagram is one approximation of what an Advanced AI Assistant may look like. Although different Advanced AI Assistants will use roughly the same components, their specific design may differ.

Advanced AI Assistants are adapted in specific ways to make them suited to their role

Advanced AI Assistants are powered by foundation models. As set out in our explainer on the topic,[18] foundation models are AI systems trained on large amounts of data scraped from the internet, which they use to generate new text, images, and video and voice materials. Examples of foundation models include OpenAI’s GPT-models,[19] Meta’s Llama,[20] and Anthropic’s Claude.[21]

The ‘foundation’ in foundation model refers to the fact that these systems can act as ‘bases’ or ‘foundations’ that an application can be built from and powered by.[22] This involves, among other things, developing an interface that allows users to interact with the foundation model in a particular way – such as sending text inputs and receiving text outputs.[23] It can also involve making changes to a version of the original foundation model in order to affect its behaviour or its performance on certain tasks, such as training it on additional, more specialised data.[24]

While the functions, performance and capabilities of an Advanced AI Assistant will be constrained in many ways by the abilities of its underlying foundation model, it can also be influenced by multiple additional factors.

The following are some of the techniques used to develop Advanced AI Assistants from foundation models.

Fine tuning : The term fine tuning refers to the process of further training a foundation model in order to adjust or improve the way that it performs specific actions or tasks. One way of fine tuning a foundation model involves training the model on additional data. Another means of fine tuning involves the provision of feedback on its outputs. A common method for this is ‘reinforcement learning through human feedback’ (RLHF). In RLHF, humans rank the different outputs generated by an AI assistant in response to a prompt, allowing the AI assistant to learn which outputs are better or more appropriate than others.[25] Another option is ‘reinforcement learning from AI feedback’ (RLAIF) where a different AI model provides feedback on outputs.[26]

Fine tuning can be used to enable a model to adopt a specific conversational style or tone of voice, or better demonstrate specialised knowledge or expertise.[27]

Chain-of-thought reasoning: Foundation models can also be adapted to increase their ability to succeed at certain kinds of complex tasks. Specifically, foundation models can be prompted and trained to engage in chain-of-thought reasoning: a process in which a model breaks a problem down into a series of smaller steps. This is an important capability for systems that may be used to solve more complex tasks like advanced scientific and mathematical problems.[28]

User interface design: An important part of building an Advanced AI Assistant from a foundation model is the creation of a user interface that enables the user to interact with the application using natural language. Although Advanced AI Assistants’ primary way of interacting is usually through language (text or speech), some Advanced AI Assistants may be multimodal and are also able to understand inputs in the form of images and video. The user interface determines how a user perceives an Advanced AI Assistant (e.g. a chatbox or an avatar) and how it may interact with them.[29]

Context window elongation: A context window is the amount of data that a foundation model can handle at one time. A larger context window means that an Advanced AI Assistant can store more information about previous interactions.[30] Many Advanced AI Assistants have been configured to be capable of storing information shared by their users for a long periods of time – sometimes even months or years.[31] This allows for higher degrees of personalisation to users as the Advanced AI Assistant will be able to recall more details from earlier interactions.

Caching: Caching refers to the saving of specific foundation model outputs (or sequences of tokens) that the model can reuse when a user asks a particular prompt. Caching can be used to save repeat prompts and stock answers, reducing the need of the model to re-process the prompt.[32] In addition to making a foundation model more cost-effective to run, caching stock answers can improve the predictability of a foundation model-powered system in particular settings and allow a developer to ensure certain questions or prompts are responded to in a particular way.[33] Caching may also be used to enable an Advanced AI Assistant to retain data (for example on previous user interactions) outside of its context window, allowing for more personalisation.[34]

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG): Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) is a technique that enables foundation models to query a database and identify specific sources of information (such as internet search results or databases) to determine how to respond to a prompt and then generate a response, rather than simply relying solely on predictions of the most probable responses. RAG can improve the accuracy of foundation model responses in some cases.[35] [36]

Safety classifiers on inputs and outputs: In addition to those built into the foundation model itself, the developer of an Advanced AI Assistant might add in further safeguards to make the resulting application more suited to use in a particular setting. For instance, an Advanced AI Assistant that is not intended for mental health purposes may have a safeguard in place that stops the AI assistant from giving mental health advice. It may shut down mental health conversations or provide a user who shares mental health concerns with links to an appropriate mental healthcare provider. Another example is the use of safety classifiers, which can reject adversarial prompts or re-generate them as a safe prompt, to prevent potentially harmful outputs from being generated.[37]

Tool use: In some cases, Advanced AI Assistants may be given access to external tools to help them reason about and act on the world. For instance, an Advanced AI Assistant may be able to access and use a basic calculator to more reliably perform arithmetic, or access a user’s calendar to enable them to organise the user’s schedule and make appointments on their behalf. More extreme examples of tool use would include an Advanced AI Assistant being granted the ability to use an internet-enabled computer, and therefore the ability to use a web browser or send emails.[38]

Scaffolding software: Advanced AI Assistants intended to interact with tools and the outside world (which we refer to as executors) also require scaffolding software. The scaffolding will prompt the foundation model in an iterative loop to generate step-by-step actions to complete a high-level goal. When the plan has been created, the scaffolding will convert the output produced by the foundation model into outputs that are in the right format to work with external tools and software, and execute these steps.[39] Scaffolding software can analyse the results of the action, and either direct more actions to take place or send a prompt back to the user for clarification. Within this iterative process between the scaffolding, the foundation model and the tools, the scaffolding may also prompt the user to approve an action before it will be executed.

The table below provides examples of how foundation models can be adapted to meet various goals using the techniques described above.

| Goal | Adaptation |

| Adapt the foundation model to use natural language, and interact in a humanistic manner with its user | User interface design to enable natural language interaction with the foundation model |

| Fine tuning of the foundation model to give application a specific ‘personality’ or tone of voice | |

| Adapt the foundation model to be more personalised to its user | Context window elongation to enable the AI Assistant to store information on previous user interactions, and on user goals and preferences over long periods of time |

| Caching of standard information or answers about the user to help the application make more consistent and personalised responses. | |

| Adapt the foundation model to be more suited to acting (or dictating action) on the world | Fine tuning to enable the application to demonstrate subject matter expertise |

| Fine tuning to encourage and enable chain-of-thought reasoning, whereby the application to breaks goals and tasks down into sub tasks and intermediate objectives | |

| Scaffolding and tool use to enable an application to convert its outputs into actions | |

| Addition of safeguards to lower the probability of an application producing undesirable outputs, taking particular kinds of actions, or acting in particular kinds of domains | |

| Retrieval Augmented Generation to improve the accuracy of responses provided by the application | |

| Caching stock answers to improve the reliability and consistency of particular actions and responses to particular kinds of requests |

Advanced AI Assistants differ from older virtual assistants in important ways

As described in the preceding sub-section of this briefing, Advanced AI Assistants are powered by foundation models, giving them different capabilities and limitations than their predecessors. And while Advanced AI Assistants have several superficial similarities to older systems, such as virtual assistants like early Siri and Alexa, the two rely on different forms of AI and therefore have different abilities and constraints.

Virtual assistants use natural-language understanding to interpret a user’s spoken or written prompts into a format easier to a computer to manipulate, and a form of ‘rule-based’ reasoning to decide how to respond to a given prompt.[40] [41] [42] Virtual assistants therefore arrive at a response to a user prompt by following a predefined set of explicit rules. These rules are typically formulated as a series of ‘if-then’ statements, with specific combinations of conditions triggering specific responses.[43]

Advanced AI Assistants, in contrast, are built on top of foundation models, which employ probabilistic reasoning. They make predictions about the best response to a given request or input based on patterns inferred from training data.

More recent foundation models (that are not yet widely in use) use a method called chain-of-thought reasoning (as outlined in the preceding sub-section), in which a model breaks down a prompt into various steps to ‘think through’ a problem, using datasets of how to break down related problems.[44] Models using this approach have been shown to make significant breakthroughs on mathematical and coding challenges, though the evidence of these improvements remains to be confirmed.

Advanced AI Assistants are therefore more versatile and better able to cope with novelty, but are more prone to certain forms of error, such as problems with logical reasoning and hallucination.[45]

The table below summarises how the technical differences between virtual assistants and advanced AI assistants translate into differences in capabilities and performance.

| Virtual assistants (powered by rule-based reasoning / systems) |

Advanced AI Assistants (powered by foundation models / probabilistic reasoning) |

| Transparency and predictability | |

| Transparent and predictable Because the decision-making process is based on explicit, human specified rules, the reasons for an input into a ‘virtual assistant’ resulting in a particular output are generally legible to human auditors (although not necessarily to users). |

Opaque and unpredictable As results are made on the basis of inferred patterns, it is hard to know what factors are responsible for a particular output and hard to predict what kind of output the model will give in response to a certain input.Intensive pre- and post-deployment testing and some other interventions (like caching, where a foundation model is programmed to provide stock answers to particular questions) can help improve the predictability of Advanced AI Assistants, although they have some limitations. |

| Degree of human control | |

| Formalisations of human intention and knowledge All of the rules followed by virtual assistants have to be explicitly written. This makes it possible for developers of virtual assistants to dictate a system’s response to particular circumstances, and limits the ability of these systems to exhibit unexpected or unintended behaviour. |

Reflections of patterns in data Because they work by inferring patterns from training data, the behaviour of probabilistic systems can be harder to control.Like rule-based systems, foundation models can exhibit bias Foundation model bias can be harder to identify and address than biases of rule-based systems.Systems based on foundation models also have a tendency to hallucinate – providing plausible-sounding but factually inaccurate information.[46] |

| Flexibility | |

| Brittle Rule-based systems can struggle when given ambiguous or incomplete information that cannot be readily accommodated by a system’s rules. |

Flexible Because they do not need to rely on a pre-programmed set of responses, Advanced AI Assistants are able to respond to queries in a flexible, non-deterministic manner. They can be prompted to change their approach to a specific query and can adapt based on previous interactions. |

| Versatility | |

| Narrowly deployable Because all of their rules have to be explicitly programmed, rule-based systems can be difficult (or at least very complicated and onerous) to apply to open-ended tasks.This is because the number of variables at play would require the rules to be prohibitively complicated. As such, they tend to only be able to address a limited number of kinds of task or request effectively. |

Versatile Foundation models are better suited to being used in a variety of domains, and for being applied to contexts for which they were not explicitly developed.In addition, Advanced AI Assistants can be trained on additional data (fine-tuning) to enhance their performance on a specific task or in a specific domain.Some of the most advanced foundation models are capable of engaging in chain-of-thought reasoning, which enables them to more effectively address certain kinds of complex and open-ended tasks. |

Challenges and questions posed by Advanced AI Assistants

As a technology that many believe has the potential to be used widely throughout our personal and economic lives, Advanced AI Assistants present multiple, overlapping issues and challenges for governments, regulators and society more broadly. The table below summarises our findings into three broad categories:

- technical challenges concerning Advanced AI Assistants’ reliability, performance and the explainability of their behaviour

- non-technical, non-systemic challenges concerning Advanced AI Assistants’ potential impact on people and particular groups, even if the Advanced AI Assistants perform perfectly well at a technical level

- non-technical, systemic challenges concerning Advanced AI Assistants’ potential impact on economic, political and social systems and dynamics, even if they perform perfectly well at a technical level.

Few of these challenges are unique to Advanced AI Assistants. However, due to the speed at which Advanced AI Assistants could become embedded in our personal and economic lives and the variety of tasks for which they might be used – and for reasons we set out below – these challenges could be made more acute, urgent and complicated by these systems.

| Challenge | Description |

| Technical challenges | |

| Reliability | Should Advanced AI Assistants become heavily integrated into our lives and economic systems, the consequences of their malfunctioning or failing to work could be severe, resulting in major disruption and loss of valuable data or content. |

| Accuracy | As systems powered by foundation models, Advanced AI Assistants can be prone to:

Bias and hallucination are not unique to Advanced AI Assistants, but the risks presented by these behaviours can be harder to detect and to address.

Moreover, due to Advanced AI Assistants’ personalisation and natural-language interface, users may be more inclined to trust (or simply not notice) biased or hallucinated outputs from such systems. |

| Explainability | The probabilistic nature of Advanced AI Assistants can make it more challenging to understand why an Advanced AI Assistant has produced a specific output than for earlier rule-based assistants.

Advanced AI Assistants’ open-ended nature, their ability to carry out a wide range of tasks, and ability to interact with other agents and elements in the world contributes to their unpredictability. |

| Alignment | Alignment refers to the extent to which an AI system’s behaviour is compatible with and reflect human normative values, laws and priorities.

Many Advanced AI Assistants will have a high degree of flexibility about how specifically to realise a user’s goals, and – given broad deployment and their use of natural language – will likely have a high degree of exposure to poorly articulated, underspecified or ambiguous requests and goals.

Alignment could therefore prove be especially challenging for Advanced AI Assistants. Moreover, given Advanced AI Assistants’ focus on guiding and taking action, the consequences of misalignment could be more severe than with some other AI systems. |

| Emergent behaviour | Advanced AI Assistants that act directly on the world could engage in patterns of behaviour that are very hard to predict and explain.

Many Advanced AI Assistants will be capable of two-way interaction with digital information and, crucially, other Advanced AI Assistants. This raises the possibility of emergent patterns of behaviour between multiple Advanced AI Assistants, which would be prohibitively complex to predict and to understand.

Researchers point to the possibility of millions of different AI Agents interacting online, each one working to further a very particular set of interests that may align or conflict with the interests of all the others.[47] |

| Non-technical, non-systemic challenges | |

| Psychological impact on users | Despite a lack of long-term empirical evidence on the subject, some experts have expressed concern that interactions with Advanced AI Assistants could be used as a substitute for meaningful relationships with humans or could come to crowd out human relationships.

Additionally, some users could experience emotional dependency on their Advanced AI Assistant, which could put them at risk for exploitation or distress if access to their Advanced AI Assistant changes.[48] |

| Practical impact on users | The widespread use of Advanced AI Assistants as executors and advisers could undermine people’s incentives to learn and practice particular skills and disciplines.[49] |

| Nefarious uses | The ability of Advanced AI Assistants to engage with people in a convincing, human-like manner and their ability to act in the world with a certain level of independence makes them well-suited for certain nefarious use cases.

For example, they could be used for the automation of scams.[50] [51] Some suggest that Advanced AI Assistants, especially with poorly functioning guardrails, could be used to make dangerous information (for example on the fabrication of weapons) more easily available to nefarious actors.[52] |

| Non-technical, systemic challenges | |

| Delegation of decision making | The diffusion of Advanced AI Assistants could result in a significant rise in the number and the kinds of decisions that the general public delegate to AI systems.

Although Advanced AI Assistants would work to further user specified goals, they could have a degree of discretion over how such goals are realised, how vigorously such goals are pursued and whether to refuse to work towards certain goals.

Widespread delegation of these kinds of decisions to AI systems would make resolutions to ongoing debates about how best to conceive of liability for automated decision-making all the more urgent.[53] It would also pose questions about the amount of influence Advanced AI Assistants (and their providers and developers) could exert over how users of their systems act on the world, and if and how this might be moderated. |

| Advanced AI Assistants as digital gatekeepers | Due to their ease and generality of use, some have suggested Advanced AI Assistants could become the main means by which many people access and use the internet and interact with digital information.[54]

The gatekeeping power that Advanced AI Assistants could exert – along with the likelihood that these systems will be provided by a small number of large firms – raises profound and urgent questions regarding market competition, consumer choice, value and fair treatment, and the future of online discourse and free expression. |

| Advanced AI Assistants and privacy | In order to deliver personalised experiences, Advanced AI Assistants collect data over a longer period of time. Because of their human-like conversational abilities, people may also be more inclined to share sensitive information about themselves.

Users should therefore be aware that the information they share with their Advanced AI Assistant may be used for wider purposes than providing a personalised experience. Their data may be used to further train the Advanced AI Assistant or its underlying foundation model, or may be sold to third parties.

Privacy policies of Advanced AI Assistants may not always provide users with sufficient information on how their data will be used.[55] |

| Distributional effects | The distributional impacts of the widespread use of Advanced AI Assistants are not necessarily positive and are contingent on several background factors. In particular, disparities in who is able to use Advanced AI Assistants, and in the quality of Advanced AI Assistants available to different groups, could exacerbate existing economic inequality. |

| Productivity, automation and labour displacement | The potential impact of the use of Advanced AI Assistants on workforce productivity is deeply contested. While assistants have shown impressive performance on some kinds of tasks (e.g. coding, mathematics and language translation), they may not perform as well at more specific kinds of economically viable or useful tasks that a user wants them to complete.

Governments will need to be careful that the benefits of any productivity gains that do emerge are fairly distributed, and are not enjoyed predominantly by Advanced AI Assistant providers and developers. |

| Environmental cost of Advanced AI Assistants | Advanced AI Assistants are resource intensive to develop and run, requiring the use of data centres and other computational hardware that uses large amounts of energy and water.[56] [57] The rollout of Advanced AI Assistants would therefore imply significant increases in energy and water consumption, with corresponding resource and environmental costs. |

Advanced AI Assistants deserve particular attention from policymakers

AI systems with the ability to communicate in a human-like manner, and to which we can easily outsource decisions, present a distinctively urgent set of challenges. Advanced AI Assistants could spread very quickly, with impacts that are difficult to monitor and snowballing, hard-to-predict effects on people and society.

Policymakers and governments will need to have a clear plan for dealing with the specific challenges posed by these systems. This is especially true in the UK, where the Government has expressed its desire to accelerate the deployment and diffusion of AI.[58]

Fully accounting and preparing for the issues posed by these systems requires us to take an inclusive view of both the kinds of challenges raised, and the kinds of systems that raise them.

To date, much of the policy and academic discussion of these kinds of systems has focused on technical and individual-level risks. Moving forward, it will be important to ensure the discourse is expanded to also include the broader structural changes and power dynamics that could emerge as a result of Advanced AI Assistants.

We also need to avoid a prohibitively narrow conception of the kinds of systems that present these challenges: systems that provide detailed guidance on exactly how to act to achieve a particular goal (which we call advisers), could be almost as impactful as those that act on the world on our behalf (the executors).

Likewise, systems that we empower to act on us (interlocutors) could also be responsible for a significant transfer of decision making from humans to AI – shifting choices about how we educate, motivate and support people from teachers, therapists and friends over to automated systems.

For these reasons, we put forward a more inclusive definition of Advanced AI Assistants than is sometimes used. While others state that an essential feature of an Advanced AI Assistant is ‘agency’ (‘the ability to act upon and perceive the environment in a goal-directed and autonomous way’[59] and generally interpreted as suggesting an ability to act directly on the world), we believe this limitation excludes many applications from the attention of researchers and policymakers. Specifically, AI systems designed to play the role of advisers or interlocutors, but unable to take action on the world themselves.

Addressing the issues posed by Advanced AI Assistants will also require more evidence The Ada Lovelace Institute’s project on Advanced AI Assistants is designed to help equip policymakers to deal with the challenges posed by this form of AI. This project is likely to include:

- further articulating and exploring the issues and challenges posed by Advanced AI Assistants, with particular emphasis on structural and political economic considerations

- surveying the gaps in current legal and regulatory protections: exploring the extent to which our current laws, norms and regulations are adequate to address the challenges posed by Advanced AI Assistants

- understanding informed public opinion, potentially including evidence of the views and attitudes of experienced users of Advanced AI Assistants

- putting forward concrete recommendations for the UK Government on how to manage the challenges and seize the opportunities of Advanced AI Assistants.

Acknowledgements

This policy briefing was lead authored by Harry Farmer and Julia Smakman. The authors are grateful to Jorge Perez, Andrew Strait, Michael Birtwistle and Catherine Gregory for comments on and substantive contributions to this paper.

Footnotes

[1] ‘Introducing Operator’, accessed 24 January 2025, https://openai.com/index/introducing-operator/.

[2] ‘Save Time and Money with DoNotPay!’, accessed 21 January 2025, https://donotpay.com/.

[3] ‘Wysa – Everyday Mental Health’, accessed 21 January 2025, https://www.wysa.com/.

[4] HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey and the ship’s computer from Star Trek: The Next Generation are two of the most iconic examples of AI Assistants from science fiction.

Liz W. Faber, The Computer’s Voice: From Star Trek to Siri (U of Minnesota Press, 2020), https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=sHQOEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT5&dq=the+voice+in+the+machine+hal+enterprise&ots=Sp1meqOcce&sig=2ZdyJDNEMfMAwwj_4Hh8WHKebIw.

[5] ‘Introducing Operator’.

[6] ‘Computer Use (Beta)’, Anthropic, accessed 21 January 2025, https://docs.anthropic.com/en/docs/build-with-claude/computer-use.

[7] Elliot Jones, ‘Explainer: What Is a Foundation Model?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, July 2023), https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/resource/foundation-models-explainer/.

[8] ‘AI Agents — What They Are, and How They’ll Change the Way We Work’, Source, accessed 20 January 2025, https://news.microsoft.com/source/features/ai/ai-agents-what-they-are-and-how-theyll-change-the-way-we-work/.

[9] ‘Sam Altman Says Helpful Agents Are Poised to Become AI’s Killer Function’, MIT Technology Review, accessed 20 January 2025, https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/05/01/1091979/sam-altman-says-helpful-agents-are-poised-to-become-ais-killer-function/.

[10] Kylie Robison, ‘Agents Are the Future AI Companies Promise — and Desperately Need’, The Verge, 10 October 2024, https://www.theverge.com/2024/10/10/24266333/ai-agents-assistants-openai-google-deepmind-bots.

[11] Hannah-Louise Shergold, ‘Generative AI: Redefining Access To Justice’, Society for Computers & Law (blog), 25 October 2024, https://www.scl.org/generative-ai-redefining-access-to-justice/.

[12] ‘Brain, the AI-Based Therapist Democratising Access to Mental Health Care’, Plain Concepts, accessed 20 January 2025, https://www.plainconcepts.com/casestudy/brain-ai-therapist-mental-health-care/.

[13] Linnea Laestadius and others, ‘Too Human and Not Human Enough: A Grounded Theory Analysis of Mental Health Harms from Emotional Dependence on the Social Chatbot Replika’, New Media & Society 26, no. 10 (October 2024): 5923–41, https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221142007.

[14] William Seymour and Max Van Kleek, ‘Exploring Interactions Between Trust, Anthropomorphism, and Relationship Development in Voice Assistants’, Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5, no. CSCW2 (13 October 2021): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1145/3479515.

[15] ‘In the near future, every single one of our interactions with the digital world will be mediated by AI assistants. ’See: ‘“The Real Revolution Is yet to Come”: Meta AI Chief Yann LeCun on the Future of AI’, Business Today, 11 December 2024, https://www.businesstoday.in/technology/news/story/the-real-revolution-is-yet-to-come-meta-ai-chief-yann-lecun-on-the-future-of-ai-456948-2024-12-11.

[16] ‘AI Personalization | IBM’, accessed 27 January 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/ai-personalization.

[17] Iason Gabriel and others, ‘The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants’ (arXiv, 28 April 2024), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.16244.

[18] Elliot Jones, ‘Explainer: What Is a Foundation Model?’ (Ada Lovelace Institute, July 2023), https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/resource/foundation-models-explainer/.

[19] ‘GPT-4’ <https://openai.com/index/gpt-4/> accessed 4 February 2025.

[20] ‘Llama’ (Meta Llama) <https://www.llama.com/> accessed 4 February 2025.

[21] ‘Introducing the next Generation of Claude’ <https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-family> accessed 4 February 2025

[22] Helen Toner, ‘What Are Generative AI, Large Language Models, and Foundation Models’, Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 2023.

[23] For example, the popular application ChatGPT is a user interface built on the GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 families of foundation models.

[24] For instance, the GPT-4 family of models is also the base for apps like Duolingo Max, that have been adapted to perform specific language practice roles for users of these services.

[25] Nathan Lambert and others, ‘Illustrating Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (Rlhf)’, Hugging Face Blog 9 (2022).

[26] Harrison Lee and others, ‘RLAIF vs. RLHF: Scaling Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback with AI Feedback’, in Forty-First International Conference on Machine Learning, accessed 27 January 2025, https://openreview.net/forum?id=uydQ2W41KO.

[27] ‘Claude’s Character \ Anthropic’, accessed 27 January 2025, https://www.anthropic.com/research/claude-character.

[28] Danny Hague, ‘Multimodality, Tool Use, and Autonomous Agents: Large Language Models Explained, Part 3’, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (blog), 8 March 2024, https://cset.georgetown.edu/article/multimodality-tool-use-and-autonomous-agents/.

[29] Kate Lister and others, ‘Accessible Conversational User Interfaces: Considerations for Design’, in Proceedings of the 17th International Web for All Conference (W4A ’20: 17th Web for All Conference, Taipei Taiwan: ACM, 2020), 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1145/3371300.3383343.

[30] ‘Why Larger LLM Context Windows Are All the Rage – IBM Research’, accessed 27 January 2025, https://research.ibm.com/blog/larger-context-window.

[31] Eunhae Lee, ‘Towards Ethical Personal AI Applications: Practical Considerations for AI Assistants with Long-Term Memory’ (arXiv, 17 September 2024), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.11192.

[32] Anthropic, ‘Prompt Caching with Claude’ <https://www.anthropic.com/news/prompt-caching> accessed 27 January 2025; OpenAI, ‘Prompt Caching in the API’ <https://openai.com/index/api-prompt-caching/> accessed 27 January 2025.

[33] Fu Bang, ‘GPTCache: An Open-Source Semantic Cache for LLM Applications Enabling Faster Answers and Cost Savings’, in Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop for Natural Language Processing Open Source Software (NLP-OSS 2023), 2023, 212–18, https://aclanthology.org/2023.nlposs-1.24/.

[34] Wael SAIDENI, ‘Understanding the Difference between Context Caching or Prompt Caching and Semantic Caching: A Step…’, Medium (blog), 16 September 2024, https://medium.com/@wael-saideni/understanding-the-difference-between-context-caching-and-semantic-caching-a-step-toward-optimizing-1a2b44d25c12.

[35] ‘What Is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)?’, IBM Research, 9 February 2021, https://research.ibm.com/blog/retrieval-augmented-generation-RAG.

[36] Patrick Lewis and others, ‘Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive Nlp Tasks’, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 9459–74.

[37] Jinhwa Kim, Ali Derakhshan, and Ian G. Harris, ‘Robust Safety Classifier for Large Language Models: Adversarial Prompt Shield’ (arXiv, 31 October 2023), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.00172.

[38] ‘Computer-Using Agent | OpenAI’, accessed 27 January 2025, https://openai.com/index/computer-using-agent/.

[39] Hague, ‘Multimodality, Tool Use, and Autonomous Agents’.

[40] Matthew B. Hoy, ‘Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and More: An Introduction to Voice Assistants’, Medical Reference Services Quarterly 37, no. 1 (2 January 2018): 81–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2018.1404391.

[41] Luísa Coheur, ‘From Eliza to Siri and Beyond’, in Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems, ed. Marie-Jeanne Lesot and others, vol. 1237, Communications in Computer and Information Science (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 29–41, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50146-4_3.

[42] ‘How Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant Lost the AI Race – The New York Times’, accessed 27 January 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/15/technology/siri-alexa-google-assistant-artificial-intelligence.html.

[43] Eleni Adamopoulou and Lefteris Moussiades, ‘An Overview of Chatbot Technology’, in Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, ed. Ilias Maglogiannis, Lazaros Iliadis, and Elias Pimenidis, vol. 584, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 373–83, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49186-4_31.

[44] ‘Learning to Reason with LLMs | OpenAI’, accessed 27 January 2025, https://openai.com/index/learning-to-reason-with-llms/.

[45] Ning Bian and others, ‘ChatGPT Is a Knowledgeable but Inexperienced Solver: An Investigation of Commonsense Problem in Large Language Models’ (arXiv, 19 April 2024), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.16421.

[46] Lei Huang and others, ‘A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions’, ACM Transactions on Information Systems 43, no. 2 (31 March 2025): 1–55, https://doi.org/10.1145/3703155.

[47] Allan Dafoe and others, ‘Open Problems in Cooperative AI’ (arXiv, 2020), https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2012.08630.

[48] Arianna Manzini and others, ‘The Code That Binds Us: Navigating the Appropriateness of Human-AI Assistant Relationships’, Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society 7 (16 October 2024): 943–57, https://doi.org/10.1609/aies.v7i1.31694.

[49] Matthias Lehmann, Philipp B. Cornelius, and Fabian J. Sting, ‘AI Meets the Classroom: When Does ChatGPT Harm Learning?’ (arXiv, 2024), https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2409.09047.

[50] ‘AI Assistants in the Future: Security Concerns and Risk Management | Trend Micro (US)’, accessed 24 January 2025, https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/news/security-technology/looking-into-the-future-risks-and-security-considerations-to-ai-digital-assistants.

[51] Gabriel and others, ‘The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants’.

[52] Jonas Sandbrink, ‘How ChatGPT Could Make Bioterrorism Easy’ (Vox, 7 August 2023) <https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/23820331/chatgpt-bioterrorism-bioweapons-artificial-inteligence-openai-terrorism> accessed 27 January 2025.

[53] Silvia Milano and Sven Nyholm, ‘Advanced AI Assistants That Act on Our Behalf May Not Be Ethically or Legally Feasible’, Nature Machine Intelligence 6, no. 8 (29 July 2024): 846–47, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00877-9.

[54] “In the near future, every single one of our interactions with the digital world will be mediated by AI assistants” ‘“The Real Revolution Is yet to Come”’.

[55] ‘*Privacy Not Included: A Buyer’s Guide for Connected Products’ (Mozilla Foundation) <https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/articles/happy-valentines-day-romantic-ai-chatbots-dont-have-your-privacy-at-heart/> accessed 4 February 2025.

[56] Pengfei Li and others, ‘Making AI Less “Thirsty”: Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models’ (arXiv, 2023), https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2304.03271.

[57] Emma Strubell, Ananya Ganesh, and Andrew McCallum, ‘Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP’ (arXiv, 5 June 2019), https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.02243.

[58] ‘Prime Minister Sets out Blueprint to Turbocharge AI’, GOV.UK, 13 January 2025, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-sets-out-blueprint-to-turbocharge-ai.

[59] Gabriel and others, ‘The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants’.

Image credit: NoSystem images