How do we ensure the voices of citizens are heard?

A summary of the second panel on the Ethics & Society stage at CogX 2020 - Day 1

On Monday 8 June, we were delighted to kick off CogX 2020 by curating the first day of the Ethics & Society stage. 25 speakers across six panels joined us to tackle the knotty, real-life trade-offs of benefits and harms that emerging technologies bring to people and society. This is a summary of the second panel of the day asking: How do we ensure the voices of citizens are heard? – which you can watch in full below:

Chair

-

Matthew Taylor

CEO, RSA

Panel

-

Kerry Furini

Online Public Deliberation Pilot Participant -

Simon Burall

Senior Associate at Involve -

Chris Carrigan

Expert Data Advisor Use My Data -

Anja Thieme

Senior HCI Researcher, Microsoft Research Cambridge

Introduction from Ada Lovelace Institute Director, Carly Kind

The previous panel ended with agreement on the fact that we need to stop focusing on data as a solution and instead gaining insight into people’s lived experience.

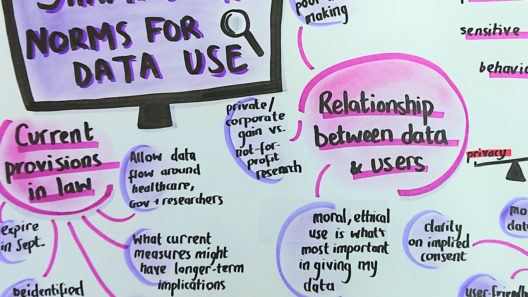

The Ada Lovelace Institute has just concluded a public online deliberation to place people’s voices at the core of the strategy to exit the present crisis.

MATTHEW:

The RSA has a long–standing interest in public deliberation and tech for good and have advocated for deliberation to be included in the exit to the crisis.

But I want to start by saying something a little different which is that for my podcast, Bridges to the Future, we interview people from around the world about how things could or should change after the pandemic. The more recent interviewee was Audry Tang (Taiwan minister without portfolio). Taiwan has been very successful in managing COVID and the three principles at the core of their strategy were: fast, fair and fun. That would contrast starkly with how we have responded, in Britain: we have been slow, as to fairness that’s still a question, and it hasn’t been a great deal of fun.

Audry pointed to the 2014 Student Sunflower movement. This was a group of students who occupied the Parliament in protest about the Taiwanese Government doing a trade deal with China, which included the opening up of their market to Chinese technology firms. That has partly led, in Taiwan, to a culture in which there’s strong relationships between citizens and government, but also the technology really feels owned by the whole population, where technological innovation comes as much from the bottom as it does from the top. And there is a spirit of fun, creativity and positivity in the conversation about how technology can be used for social good. This is the approach they’ve brought into this crisis and helped them to be incredibly successful.

In the UK, we need to focus on people’s concerns on technology and maintain the focus on systemic inequalities and how technology can exacerbate some of those issues. We also need to keep in mind the upsides and that things can be much better than they are now. The UK is probably 10 years behind Taiwan and the way they use data-driven technology to improve and strengthen the relation between state and people.

KERRY:

I am probably the standard person you will find in a poll or a survey (middle-aged white woman, married and have two children). I was part of the online deliberation work that the Ada Lovelace Institute and Traverse conducted online on the strategy to exit the COVID–19 crisis. It was very interesting to talk to people from all walks of life. We managed to get a lot of ideas out of people and viewpoints across society. Trust and ethics were central to our discussions.

We looked closely at current affairs and especially the Dominic Cummings incident and the killing of George Floyd. Discussing the Cummings incident, they felt there was a lot of imbalance between what people and politicians can do – a ‘them and us’ mentality. For instance, a question that emerged was: if contact-tracing apps become mandatory, do politicians also have to use them?

The killing of George Floyd also brought up a lot of questions on segregation and racism and how a contact tracing app could become vehicle of discrimination. Would it be used to police your movements? There is the example of a recent case on Korea, where a person’s movements were tracked and then used to stigmatize them.

Also, different people will have different concerns, my husband, for instance is extremely careful, as he is immuno-compromised. Not everybody feels the same about technology and there are differences in how we might feel about it before and after the lockdown.

The group felt citizens should be involved in the process of data use throughout. During the online deliberation the group heard speakers and became an informed public on how data could be used. The main concerns the group raised were:

- Is the app safe? Is it going to be used for evil rather than good? Are we going to be judged? Are going to feel like we have to change our habits in a permanent way?

- How do we know the app works? Policymakers need to take citizens into account. Are people going to be able to use and understand the apps?

MATTHEW:

You speak eloquently about the issues. Were you an expert going into this process? What were your expectations going into it and how has the process changed how confident you are about these matters?

KERRY:

I was no expert going into this, but I would see the daily briefings and see the people reacted on social media. I feel it is important to listen to the research and, if anything, this has made me more keen to research into how these things work—for instance, how manual tracing and an app might work together.

SIMON:

I am going to talk about why we need to engage citizens and how we ensure that their voices are heard. We need to hear citizens and COVID is the perfect case study for this. With regards to many aspects of this crisis, for instance track and trace, which is usually understood as a problem of data collection and tech—if the tech works then it will be fine, but public engagement raises different issues in this context: how do we value the health of individuals and the economy? How do publics balance those things? Getting the economy right will have other implications for other health issues? How do we balance the health of young vs health of old? How do we balance the needs of different geographic communities? These aren’t technology problems, they aren’t problems you can answer with getting the data right.

There are only social solutions to the above questions and good public engagement can help and it can help you do understand three things:

- What the public wants e.g. what the public thinks the right answer is to the question of how we balance the economy vs. health.

- The values that underpin why a part of the public is preferring a solution as opposed to another. What are they taking into account when they balance the trade-offs?

- How different publics uphold different values.

There are different kinds of public engagement: from polling to consultation, to long form of deliberation, where we bring together a relatively small group of people (25 people broadly reflective of the population) to answer a specific policy question. These are concrete processes to ensure people’s voices are heard.

Listening with intent is key to all this. Too often politicians and civil servants want to know what the public thinks, they commission a quick engagement process, but then ignore its results. Involve has created a nine steps process to engaging publics. The nine steps start from asking: what are you engaging the public for? This needs to be established and understood early. In the UK, there needs to be a strategy for 10 years going forward, which starts by taking a step back and seeing where the public can contribute and to what.

MATTHEW:

We know deliberation works and people like it and feel enriched from it. The two big problems in the UK is that it is not mainstream for policy, and we have not gotten right the relationship between the deliberation and how the politicians use its findings.

SIMON:

Why is it not happening? We have a very narrow part of the population taking decisions and they are scarred by the black-and-white state of the public debate. They fear that public engagement would only result in the same.

CHRIS:

I have become increasingly interested in where the user voice is heard in health data. The problems we face are not technological, but what we do with the data, how we ensure it is used well, these are the real problems.

Users, carers and families compose the independent patient movement that is UseMyData. We need to highlight how data can improve people’s lives. We see a fear among governors of what they could be told by the public.

If you are an individual, it is difficult for you to ensure that your voice is heard. Instead, if you are an organisation it is much easier. UseMayData is collating people’s data and bringing people’s voices together. I coordinate with our members and get their responses and feed them into the deliberation directly, not with a one-line answer, but with a spectrum of opinions. UseMyData, in this way, is seen as a source and an authority. What we say is that we need to be the patients’ voice.

We also highlight where organisations are looking for very engaged members and we can source that. We work as a bridge. We want to show the benefit of using patients’ data.

At a certain point, it is also a matter of recognition, say a bit of a thank you. A UseMyData member has come up with a users’ citation, to recognize that none of the studies are possible without patients’ data and their collaboration.

What happens coming out of COVID, there is a huge amount of change with data and what is done with it. What out of it do we want to keep and what do we want to stop doing? We have data joining up, single data–gates. We need to talk about this, and the only way to do it is transparency or, as we say at UseMyData ‘say what you do and do what you say around data’.

ANJA:

In my work I try to follow a deep human-involved approach to tech, developed responsibly and in alignment with people’s values and ethics. I use ethnography to help consider people’s perspectives, concerns and critiques.

One example of good practice is Seeing AI, which is a very popular among blind community. It has been successful because it was initiated by people with a lived experience of a visual impairment. It has a feature where you can take a picture of an object and it can automatically create a caption for that image so it can tell you what is going on around you.

Now, if you are blind there are a lot of considerations to be made about how you are taking pictures (blurry, out-of-frame). You may also want to take pictures of things that are unexpected and a person with good vision may not consider, for example if you go into a hotel room for the first time you may want to figure out where the power sockets are. We also learned that people who are blind are not interested necessarily in objects, but in people. So this creates some tensions, such as around privacy.

We certainly want innovative AI tech that can use image processing to make the world more accessible to people who are blind, and yet at the same time we don’t want to infringe on other people’s rights to privacy. That requires careful consideration and dialogue with all stakeholders who might be implicated. This is where public engagement is at the heart of everyone to be able to succeed.

But a contrasting example, is the trend to develop machine learning that can detect or diagnose if someone has a mental health problem by collecting and analysing their social media data. This practice can help with diagnosis, perhaps even earlier than they may have suspected. It can also help raise awareness of the problem and validate their experience or encourage them to seek help.

But you can imagine that not many people will be aware that their social media data is being analysed for the purposes of mental health screening but considering that a person may not know that their social media data is being evaluated. Further to that, a diagnosis can come with many problems. You have some really careful balancing acts. Engagement is crucial to help understand what AI technology and data uses people find acceptable and what technologies people should perhaps not develop.

This is a balancing act for technology companies. On the one hand they want to drive forward innovation and see what technology can do, but we also need to pause and think carefully about how the technology plays out in our lives and what the broader ethical and social implications might be.

Related content

A rapid online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies: building public confidence and trust

Considering the question: ‘What would help build public confidence in the use of COVID-19 exit strategy technologies?’