How to make a Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about how we ran the Citizens’ Biometrics Council

1 April 2021

Reading time: 14 minutes

Throughout 2020 the Ada Lovelace Institute convened the Citizens’ Biometrics Council, bringing together 50 members of the UK public to deliberate on what is or isn’t ok when it comes to the use of biometrics.

Since we concluded the process and launched a report about the Council, we’ve had several conversations with policymakers, researchers, civil society organisers and technology developers about the Council.

Each of them was deeply interested in the day-to-day nuts and bolts of how we developed and ran the Council. How did we choose what information to present to Council members? Did we use Zoom or Google Meets when we went online? How did we choose people to take part?

Below we answer some of the most common questions, to share our experience, which others can draw from. You can read more about the Citizens’ Biometrics Council in our final report.

Final report of the Citizens' Biometrics Council

Recommendations and findings of a public deliberation on biometrics technology, policy and governance

What exactly is a Citizens’ Council?

A Citizens’ Council is a type of ‘mini-public’. Broadly defined, these are a range of approaches that bring members of the public together through a series of workshops to deliberate on a particular policy or societal question.

Participants in a mini-public will engage with information about a topic, hear from experts and ask them questions, consider issues in small groups and through creative tasks. They will usually result in the formation of collective recommendations or a ‘verdict’ in response to a focused question.

Mini-publics can be relatively small, such as citizens’ juries that bring 20 to 30 people together for two or three workshops across a week or two. Or they can be relatively large, such as citizens’ assemblies that convene 100 people (or sometimes more) across months of deliberation.

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council was a mid-sized mini-public – it included 50 members of the public, split into two groups, and around 60 hours of deliberation in total. It was planned that each group would participate in one weekend of workshops a month for three months (COVID-19 disrupted this, see below).

Why use this approach?

Mini-publics enable the consideration of complex topics that involve subjective or value-based questions, and create space for citizens to articulate what they think should happen about those topics.

Biometrics is one such complex topic, and while we had previously studied public attitudes towards facial recognition through a survey, we wanted to use a deliberative method to build a deeper understanding of public perspectives and allow participants in the Council to develop their own recommendations for addressing the challenges raised by biometric technologies.

We settled on a ‘council’ as the appropriate scope for this, as a citizens’ jury (or similar smaller method) may not have been able to appropriately consider the depth and breadth of the topic of biometrics.

A citizen assembly may have been able to consider greater depth, but it would have risked losing focus.

Public deliberation is also time and resource-intensive, and a citizens’ council was the most ambitious yet realistic scale of mini-public possible within the resources of the Ada Lovelace Institute at the time we launched the project.

How did Ada find people to take part in the Council?

To deliver the Council, we commissioned and partnered with public engagement specialists Hopkins Van Mil. To invite people to participate in the Council, Hopkins Van Mil worked with a market research recruitment agency to find participants according to a recruitment specification.

We wanted to ensure diverse representation on the Council, so we set the recruitment specification to achieve a broad mix of ages, genders, socio-economic backgrounds, ethnicity, disability, political preferences, urban or rural locations and attitudes towards data.

The goal was not to achieve statistical representation but to ensure that diverse perspectives, experiences and backgrounds of the UK population were reflected in the Council. We engaged Council members in an intersectional way, asking them not to represent a particular view by virtue of fitting a particular demographic, but to share their unique perspectives based on a holistic understanding of their own experiences. Our thinking was inspired in part by this article on diverse sampling in mini-publics.

Additionally, we wanted to boost our engagement with people from minority ethnic groups, people who are disabled and people who identify as LGBTQIA+. This is because these groups were identified in prior research as being both underrepresented in debates about biometrics, as well as at risk of facing particular or unique burdens of harm from the use of biometrics.

We convened a focus group – called Community Voices groups – for each of these demographics, who met once before the Council convened to inform the design of the project, and once after to review the Councils’ findings. Some members of the Community Voices groups also sat on the Council. The team at Hopkins Van Mil engaged with these groups by working with community charities and support groups to invite their members to participate.

Biometrics isn’t a well-known topic and can be quite technical and dense. How did we enable participants to understand and engage with it?

An unfortunate assumption is too often made that the general public aren’t able to grasp and engage with complex topics in any meaningful way. This is a mischaracterisation. The reality is that the vast majority of people can, and do consider complex topics (and do so every day), but they cannot do so meaningfully if they do not have the time, reason, support or access to relevant information.

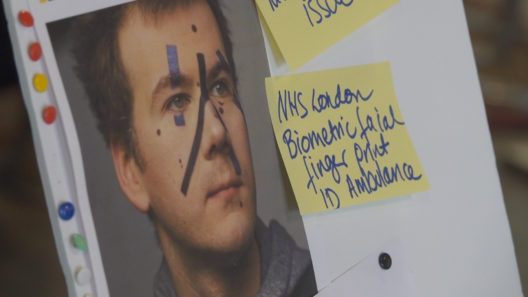

Public deliberation projects are designed specifically to overcome this by providing people with the materials, time and access to expert speakers so that they can consider a topic in depth. In the Citizens’ Biometrics Council, we invited experts from a range of perspectives – from the biometrics industry, policing, regulators, policymaking, academia, campaign groups and more – to speak to the Council and answer questions. We also shared materials from a breadth of news media, business literature and research literature.

The challenge was finding materials and speakers that did not frame the deliberation in such a way that biased or unfairly influenced the outcome. An expert from a technology company will have a particular viewpoint, while materials produced by an anti-biometrics campaign group will have another. Producing neutral material is not a viable option either: we at the Ada Lovelace Institute could attempt to present evidence we had gathered to Council members, but in doing so we would still have to interpret materials, which rick inputting our own influence.

Instead, we sought to openly present a balanced range of information to the Council, by working with the project’s oversight group (drawn from a range of sectors) to ensure the experts and materials covered a broad spectrum of viewpoints within debates about biometrics. Crucially, we didn’t present any information without allowing the Council members to question it thoroughly and discuss it with one another.

In other words, we invited our Council members to become the experts, investigators and researchers themselves, navigating evidence and information with support from the facilitators and guided by the project’s question: what is or isn’t ok when it comes to the use of biometrics?

What impact, change or difference did the Citizens’ Biometrics Council have?

Charting the impact of mini-publics is a tough challenge: often impact is not immediate or clear, and instead happens slowly and as part of large societal and policy change.

Sometimes, mini-publics like the Council are initiated by public bodies, like local or national councils. In these instances, there’s often a mandate that the public body will listen to and act on the outcomes of the project, making charting change a clearer task.

However, as an independent research institute, the Ada Lovelace Institute has no such remit to enact policy changes recommended by the Citizens’ Biometrics Council. Instead, our goal is to ensure that the policymakers and technology developers who can respond to the Council’s recommendations engage with the project and its findings.

One primary vehicle for this is publishing the Citizens’ Biometrics Council report and getting it on the desks (or in the email inboxes) of relevant organisations and institutions. Another vehicle is through advocating for the Council’s recommendations through meetings, events, conferences and other communications channels.

We made all this clear to Council members: the Ada Lovelace Institute could not promise that everything that they recommended would be acted upon – we have neither the remit nor mandate to ensure that – but we would commit to doing our best to ensure the right organisations paid attention to the Council’s conclusions.

Since publishing the report, we have aimed to do just that. As of 13 August 2021, we have conversations with representatives from over 20 NGOs, journalists and research organisations, across the UK and Europe, about the Councils’ findings and method. The Council has been referenced in a number of high-profile media outlets including the Financial Times, Politico and Nature.

We have also referenced the Councils’ findings in several responses to policy consultations, and alongside an independent review of the governance of biometric data, the Council’s perspectives and recommendations continue to inform Ada’s ongoing work to influence and shape biometrics policy in the UK.

What impact did the COVID-19 pandemic have on the process?

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council was originally planned to take place via a series of in-person workshops in Bristol and Manchester across weekends in February, March and April 2020. We were almost exactly halfway through the process when the UK went into a national lockdown in mid-March.

We immediately postponed the remaining workshops in the hope we could reconvene the participants in the autumn. As the pandemic went on, it became clear that reconvening in person wouldn’t be possible without a long delay. We didn’t want to indefinitely postpone, however, as the Council’s deliberations on biometrics were only becoming more important as society moved online, and new digital tools emerged to tackle the pandemic and support social distancing and lockdown.

We redesigned the process with our delivery partners at Hopkins Van Mil to work online, via Zoom. In summer 2020 many public deliberation and engagement projects were rapidly adapting to work online, and Hopkins Van Mil were among the pioneers developing, sharing and learning best practice in how to do that.

We reconvened the Council via a series of one-to-two-hour online workshops across September and October. Some Council members needed additional support to participate virtually, including guidance on using online tools like Zoom. Some others had to drop out of the process – understandable given the additional stresses many people faced during the pandemic. We additionally recruited a small number of people to maintain our cohort size.

Many Council members reported that participating virtually was actually a great way to engage, meaning they could fit workshops around personal commitments. In our final report, we reflect more on the differences between online and face-to-face deliberation.

Finally, COVID-19 caused a shift in the topics of discussion, something which we welcomed and embraced. Council members reflected on the new ways biometrics could be used in the wake of the pandemic, and considered the opportunities and ethical questions that raised.

What’s next?

The Council was designed to have a finite running time and clear endpoint. This was to keep the project focused, feasible and directly working towards a clear ‘conclusion’ moment. However, during the process, Council members expressed a desire for ongoing public engagement on the topic of biometrics, and this was the subject of some of their recommendations too.

We do not have current plans to run a continuation or additional version of the Citizens’ Biometrics Council at the Ada Lovelace Institute. Though we echo the need for continued public engagement on this topic, we believe the responsibility to instigate this engagement sits with those developing, deploying and governing biometrics technologies. To achieve the meaningful involvement of the public advocated for by the Council, the institutions shaping and designing biometrics technology, policy and governance need to actively engage the people the technology affects in their decision-making process.

We will continue to advocate for this through our ongoing work to share the Council’s findings and wider research in this area, and we will include members of the Council in that work where they have the interest to do so, such as by inviting them to events to speak about their experience on the Council, as we did at our report launch.

What have we learned about running a Citizens’ Council and what would we do differently?

We learnt that specifically engaging with and embedding underrepresented or marginalised voices is not just invaluable to ensuring diverse, relevant, robust and constructive public deliberation, but that no public engagement project can be considered complete or meaningful without it. This is especially true when the topic of concern is technologies that carry burdens for those already marginalised in society.

We also learnt that conducting deliberation online is neither worse nor better than face-to-face: it is simply different. We suspect that in the future, public deliberation approaches will consider online methods (or even hybrids of online and in-person) as part of a suite of tools and methods that can be used in fostering robust public engagement.

In future, we’d consider using a broader range of collaborative tools. When we adapted to Council to work online we introduced Zoom as our method of conducting the workshops, and continued using an online engagement platform to share materials with the participants. We didn’t introduce any collaborative tools like virtual whiteboards or shared text editors as we were concerned about introducing barriers for those participants who might be less familiar with these systems. If designing an online deliberation from the ground-up, it is possible to use more complex virtual tools, assuming there is the time and capacity to support participants to use them, and that the tools are embedded in the methodology. In this instance, we were adapting an in-person process to work online, and wanted to reduce the friction of that change for our Council members.

Lastly, less a lesson and more a reminder: the Citizens’ Biometrics Council showed us, once again, people have immense appetite to engage with these processes, to consider topics with care, to collaborate with their fellow citizens, to work together towards a better future and to have their voices heard.

Related content

What is or isn’t OK when it comes to biometrics?

Reflections from round one of the Citizens' Biometric Council.

Public demands stronger regulation for all biometric technologies, the Ada Lovelace Institute finds

The Ada Lovelace Institute's Citizens' Biometrics Council concludes that biometric technologies require stronger regulation

The Citizens’ Biometrics Council

Report with recommendations and findings of a public deliberation on biometrics technology, policy and governance

Beyond face value: public attitudes to facial recognition technology

First survey of public opinion on the use of facial recognition technology reveals the majority of people in the UK want restrictions on its use