Why algorithms aren’t the answer: what the public needs to trust technology

A ten-point checklist for the Test and Trace team working on contact tracing app 2.0, based on the findings of rapid online public deliberation.

17 August 2020

Reading time: 6 minutes

On Thursday last week, and largely overshadowed by A level results day and the controversy generated by the use of a grade-awarding algorithm, the UK Government/NHSX Test and Trace relaunched the pilot of the second release of their contact tracing app.

They could have been burying the launch on a busy news day, but our initial analysis suggests that wasn’t necessary – unlike the app tested on the Isle of Wight in May, this new iteration comes with a technical build that has more thoughtful caution, greater upfront transparency (the data protection impact assessment [DPIA] was published on the day of launch), and responds to public concerns about privacy and data storage by using a decentralised model built on Google/Apple technologies. It’s also more clearly integrated into the broader public health strategy, and there is a more diverse population group involved in the first stage of piloting.

If it’s proven to be effective, there is a clear use case for a contact tracing app: a rising rate of infection beyond a level that manual contact tracing can manage, and the ability to identify unknown social contacts. So this second release isn’t just about recouping investment – though we shouldn’t lose sight of the £12 million the app has cost so far – or an academic problem. If we get a second wave, we will need these technologies to work as part of a holistic public health strategy. What would be needed to ensure the public trust it this time?

At the height of lockdown, and just as the first-release app was being unrolled, the Ada Lovelace Institute, in collaboration with Traverse, conducted an in-depth public deliberation that enabled a diverse selection of people to explore the evidence, cross-examine experts and discuss and debate the role of technologies in a crisis.

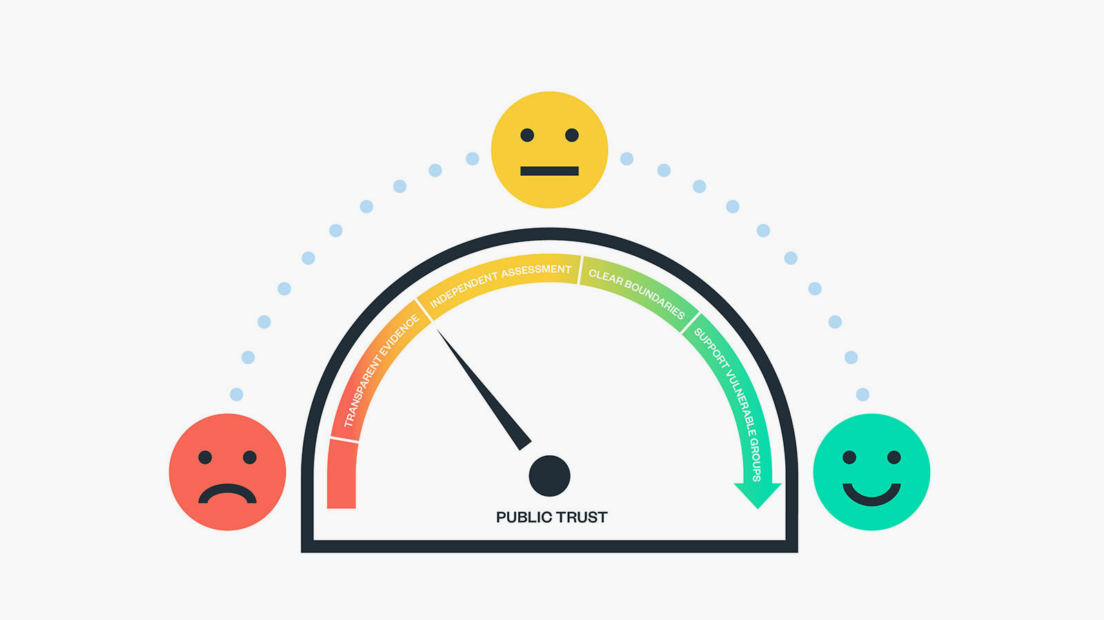

Addressing the question ‘Under what circumstances do citizens think that technological solutions like the COVID-19 contact tracing app are appropriate?’, the ‘mini public’ or ‘citizens jury’ developed a thoughtful set of criteria by which COVID-19 tech could and should be trusted.

Building directly on the public’s steers, we’ve developed a ten-point checklist for the Test and Trace team working on the app 2.0:

- Articulate the purpose of any technology.

- Publish the evidence that the technology achieves its stated purpose.

- Publish more and publish sooner.

- Set up an independent Group of Advisors on Technology in Emergencies (GATE)

- Reinstall an Ethics Board with a wide remit and diverse voices.

- Empower users.

- Outline data practices upfront.

- Acknowledge and address potential social risks, particularly to the most vulnerable groups, head on.

- Build technology alongside policy and law.

- Be conscious about the values being built into the technology.

The app team can congratulate themselves on ticking off some big concerns with this release. But the technology itself is only the start of the story. The team in charge of the app should have three areas at the top of their to-do list:

First, they must collect and publish the evidence that the app is effective and valuable.

There are big questions about whether the app can deliver technical accuracy – current modelling suggests that 45% of cases where you are warned you are within 2 metres of someone will be incorrect (false positive – meaning the risk is smaller than the app notifies, and you are actually at a lower risk of having been exposed to the virus), and 31% cases will be missed (false negative – meaning the risk is greater than the app notifies, and you are at risk of having been exposed to the virus). This needs to be road-tested in the real-world pilots that are planned in the Isle of Wight and London Borough of Newham, and ideally, accuracy must be improved.

Technical accuracy will be essential but is not sufficient to secure trust. The app team needs to build evidence about the app’s impact on public health and the spread of the virus. They need to use the pilots to assess what the behavioural impacts of the app are in the real world, measuring adherence and taking particular care to look at unintended consequences – a high rate of false positives may well lead to people not taking alerts seriously when they do receive them. At its heart, this app asks citizens to trust it when it tells them to disrupt their lives and isolate. It must be able to prove that disruption is justified for the sake of public health, that ‘the app will save lives’.

Given the first listed aim of this app is to ‘create an enduring new medical technology to manage public health’, research should be designed in to assess the value of the app as well as its effectiveness. It will be important to monitor whether individuals asked to self-isolate are doing so correctly, but also whether the app is finding cases that would not have been traced through manual contact tracing – and to compare the cost and value of the two approaches against their effectiveness.

Second, they should urgently set up independent oversight.

We’ve recommended the creation of an independent Group of Advisors on Technology in Emergencies (GATE) with a remit to examine the evidence base for their use, assess and advise on their likely impact, and weigh the social issues raised by the technologies. While the creation of GATE would require Government backing and funding, it should be within the power of the app team to reinstall an Ethics Board – with a wider remit and ‘teeth’ to shape, stop or critique national roll out.

Finally, the team must liaise with Government about the law and policy that need to be in place for the app to be successful.

Technology tools will be judged as part of the system they are embedded into – the whole system must be trustworthy, not just the technology – and that may require legal protections to give ironclad confidence that tools will not be misused by unscrupulous employers, or allow scope creep from government overreach (in policing or migration, for example).

The system must be built with policy mechanisms in place to support use and adherence – for example, employment protection or wage replacement may be required to support people to self-isolate. A lack of policy support around isolation when it is at a more targeted or individualised level risks further divergence in public health outcomes between rich and poor communities, as only those with existing resources will be in a position to comply.

For people to be willing to download and use the app, its purpose must be clear: the Government must be able to explain to the public what the app is for so that people download it and listen when it tells them to isolate. The rapidity and availability of testing will determine the level of disruption individual isolations will cause.

The tentatively good news is the new team, headed by Baroness Dido Harding, seem to be taking steps to ensure that this version of the app is built with public legitimacy – some painful lessons have evidently been learned from the first development.

The use case for the contact tracing app is a rising infection rate when manual contact tracing cannot identify the unknown person you stood next to on a bus or sat next to in a café.

But can the team demonstrate with evidence that it will help stop the spread of COVID-19?

That is the critical task the team needs to be able to answer for it to be used and trusted – and the answer must take us beyond the design of the app and into the real world.

Find out more:

-> Find out more about our rapid online deliberation

Related content

Rapid, online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies

Rapid, online deliberation with 28 members of the public on COVID-19 exit strategies.