Standardised access: the tension between scale and fit

Disability-led access as a lens to rethink the meaning and potential of responsible technology

24 May 2021

In 2022, JUST AI moved to being hosted by the LSE. Learnings from this pilot project have contributed to greater understanding of the challenges and approaches to funding and hosting fellowship programmes, within the Ada Lovelace Institute and in the development of a broader data and AI research and funding community globally.

On 21 April 2021, the JUST AI Network presented a conversation with Sara Hendren, author of What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World, and Sarah Drinkwater, Director of Responsible Technology at the Omidyar Network, to explore ‘access’ – with a focus on disability-led access – as a way to rethink the meaning and potential of responsible technology. The conversation was moderated by Louise Hickman, Senior Research Officer with the JUST AI Network, and facilitated by Alexa Hagerty, Research Fellow at University of Cambridge Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence. The full recording of the event is available here.

In this blog post we reflect on one of the themes that came up in this discussion: the tension between scale and fit.

‘Will it scale?’ is a question that drives the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) technologies. Scalability – the ability to grow efficiently, generally through various forms of standardisation – is the dominant approach to innovation in the technology sector. By contrast, critical disability studies bring attention to ‘fit’ – exploring the nuances of interactions between the body and the built world, and investigating what is at stake at the very particular and specific meeting of the two.

What are the tensions between scale and standardisation on one hand, and the fit between individual bodies and the world on the other? And what are the possibilities of technology to mediate or transform this tension – given that technologies are largely developed for scalability?

Sara Hendren, in her book What Can a Body Do? offers an interesting historical example of the tension between standardisation and fit. In the 1940s, the US Airforce, looking to reduce crashes during training flights, realised that plane cockpits, which had been designed based on average measurements of military recruits with the idea that they would therefore ‘fit most pilots, most of the time’, actually did not fit a single pilot perfectly. Adjustable features like pedals and helmet straps, which could be adapted to a range of bodies, were needed for safer flights. In other words, scale without fit was dangerous.

In a very different context, Louise Hickman has identified tensions between scale and fit in her work on real-time captioning. Automated captioning has been developed with the promise of scalability – that it can be seamlessly added to video chats with the press of a button, for example. No humans required! Yet, conceptualising captioning as a scalable technological product ignores the ways in which the labour performed by human captioners involves ‘fit’ – requiring real-time adjustments such as understanding accents and drawing on previous knowledge and context.

When considering scale and fit, the point is not to choose one over the other or to resolve the tension between them. Rather, we can use the tension as a vibrant question that leads us to a deeper analysis of the relationship between technology and access.

The accessible icon project is an instructive guide to keeping tensions alive in our analysis of accessibility. This project, led by Sara Hendren and Brian Glenney, transformed the original International Symbol of Access, first designed in the 1960s, by superimposing an active red figure over the blue rectilinear geometric shapes. In its early street art form, the project used clear decals to change wheelchair icons in public signs from symbols of stasis to mobility-in-action. Both the original and edited versions of the icon were simultaneously visible, eliciting a tension and a space for questions: ‘Who has access – physically, yes, but moreover, to education, to meaningful citizenship, to political rights?’

By keeping both scale and fit in view, and in the spirit of lively questions, our conversation with Sara Hendren and Sarah Drinkwater asked how the credo of scalability in the technology industry encodes paternalistic notions of access and inclusion. We also considered how we might use tools of critique but also strategies of repair. As Sarah Drinkwater said, ‘We have to keep pushing, imagining, asking, being in a state of wonder.’ This is the creative capacity of human intelligence that can reimagine technologies in support of flourishing and the creation of fit between bodies and worlds.

One way of encompassing generative tensions between scale and fit, and critique and repair, is to commit to a practice of prototyping. The prototype is profoundly pragmatic but also full of possibility – uniting the question ‘How can we build a better world?’ with ‘What are we going to build on Tuesday?’ Disabled people have a long legacy of expertise in reimagining and remaking the built world. As Sara Hendren said, disability-led design can show the way in creating technologies ‘with all our wits intact, that is, with our human values’.

It is this creative and intellectual tradition that we need to centre as we prototype technologies. The prototype is by definition biographical, archival, sociotechnical, and yet unfinished and porous. This is another configuration well-suited to embracing the open questions of scale and fit. In prototyping, in other words, access is not standardised, but continually under construction.

Watch Access as a responsible technology? An exploration of ‘access’ as a way to rethink the meaning and potential of responsible technology, with Sara Hendren and Sarah Drinkwater in full below:

This video is embedded with YouTube’s ‘privacy-enhanced mode’ enabled although it is still possible that if you play this video it may add cookies. Read our Privacy policy and Digital best practice for more on how we use digital tools and data.

Image credit: The Accessible Icon Project

Related content

Access as a responsible technology?

An exploration of ‘access’ as a way to rethink the meaning and potential of responsible technology, with Sara Hendren and Sarah Drinkwater

JUST AI – Prototyping ethical futures for data and AI

Taking a creative, humanities-led approach to questions of AI ethics

To be seen we must be measured: data visualisation and inequality

How data, bodies and experience entwine.

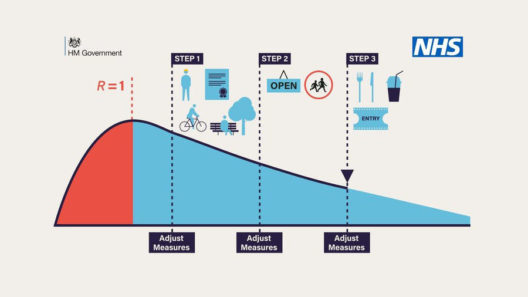

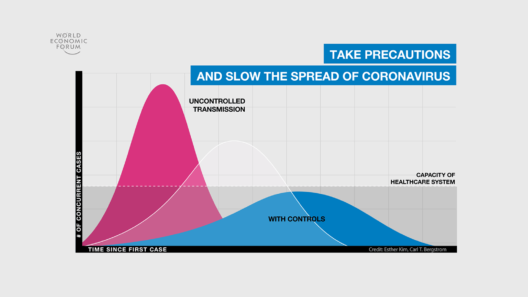

What is visualised is realised: models and the fallacy of risk

How mathematical models of infection structure the messages people receive about risk and responsibility.