Making interoperability work in practice: forms, business models and safeguards

Equitable interoperability as a standard

16 December 2021

Reading time: 25 minutes

The article ‘From “walled gardens” to open meadows’ showed how anti-competitive practices could be addressed via interoperability and to what effects. Further exploring the questions and challenges around this intervention, this article focuses on more practical terms: what kinds of interoperability would most effectively break down platform power? And what type of safeguards would be necessary for reducing negative impacts?

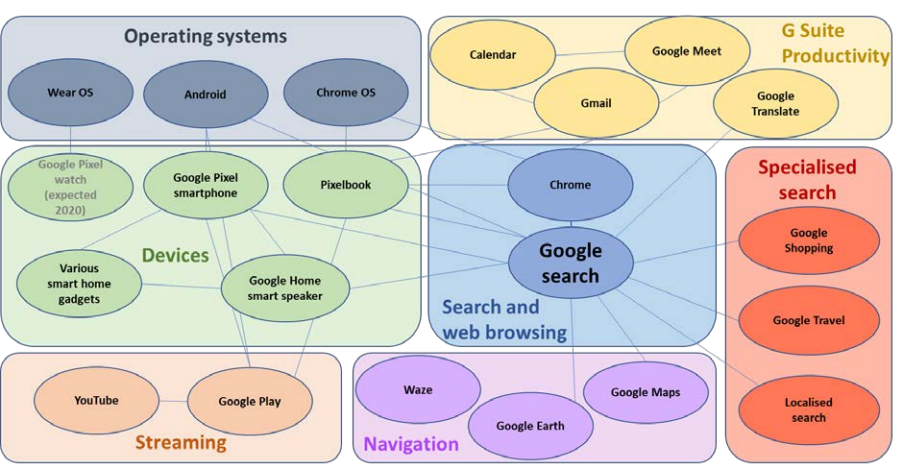

One of the elements that contributes to large companies consolidating their power is their privileged access to user data and using compatibility between their own services to grow ever-larger, and expand into adjacent markets as digital conglomerates. Google’s consolidation of their business model into their operating system and search is a good example of this (as shown in Figure 1).

Addressing the anticompetitive effects of these digital conglomerates requires a combination of limiting that use of personal data under data-protection law, alongside providing carefully targeted access for external competitors – ideally with users explicitly deciding whether/how their data is shared, or in effectively anonymised form (which can be difficult to achieve in practice).

Where large firms provide privileged access within their own ecosystem of services (such as Facebook’s ongoing integration of its three separate messaging services, Apple’s restriction of access to iPhone contactless payment hardware to its own payment service, or Google, as mentioned above), they should also be required to allow competitors similar access at users’ direction – with processes in place to assess agreed security, privacy and other standards. Greg Crawford and colleagues have called this idea equitable interoperability.1

What kinds of interoperability would most effectively break down platform power?

Interoperability as a pro-competitive measure varies by sector and service, meaning that careful market analysis (like that undertaken by the UK Competition & Markets Authority in the retail banking and online platform sectors) is required to show what types of interoperability would be most effective (and proportionate) in stimulating competition.

In the UK financial sector, this has involved enabling data interoperability and cross-provider payments for personal and small business current accounts of the nine largest UK banks;2 mandating competitor access to query and clickstream data from Google; or initially limited interoperability for competitor social-media services with Facebook (with the possibility of later moving to a fuller model).3 The latter would reflect developments in France, where the Conseil national du numérique has already called for limited interoperability requirements for social media.4 And freedom of expression group ARTICLE 19 has called for social media platforms to offer users the choice of interoperable third-party recommendation and curation systems, to ensure a plurality of choices of content moderation.5

A careful analysis of the technical protocols and business relationships underpinning services, such as 5G, earlier wireless and broadband networks, and smartphone apps, can highlight regulatory opportunities for increasing their modularity by requiring incumbent firms to support interoperability between components of their services with competitors’ software or hardware.6 One of many examples is the Open Radio Access Network standard,7 being promoted by European telecommunications manufacturers and the US Government, as an alternative to Huawei 5G equipment.

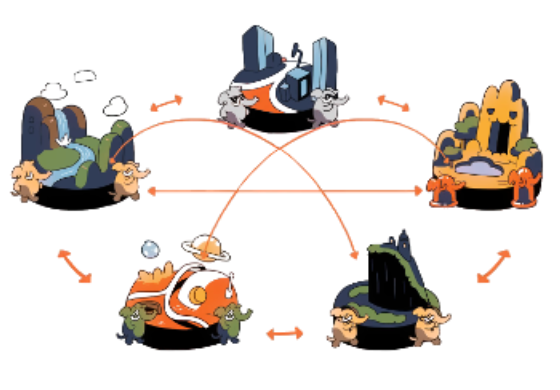

There are technical components used in many services, such as for identity management (see Figure 2), where increased modularity would allow users to plug in their own choice of component to larger services. (The EU is planning an update of its eIDAS Regulation in 2022, which would provide a specific legislative mechanism to require this.) Users wanting maximum control over their data could store it on their own hardware, such as a FreedomBox.8

Siddarth and Weyl suggest managing such common components and protocols as a digital commons, ‘for an inclusive and sustainable ecosystem with shared social benefit’ (as well as ‘a commons-oriented infrastructure for data coalitions, that allows for active participation in and ownership over shared datasets’ generated by the participants).9

In comparison, the German Cartel Office has required Facebook to seek explicit consent from users to profile their activity elsewhere on the World Wide Web, a remedy more familiar from data protection law – although that order is still being contested through the German and European courts.10

While a number of competition authorities are increasingly paying attention to non-economic factors in their analysis – for example, environmental sustainability11 – individual empowerment and social value are higher-level political goals that require a complex and multifaceted approach. They can best be addressed through a combination of an evolution of competition-law frameworks (e.g. to more highly prioritise the modularity and diversity of available products/services in a market over efficiencies from vertical integration); stronger enforcement of data and consumer-protection laws; and market-specific regulation.

Can interoperability be profitable?

Requiring the largest social media companies to enable interoperable filtering and recommendation services, as proposed by ARTICLE 19, is a useful concrete example to analyse the business model impact. Daphne Keller and Nathalie Maréchal have noted two significant and related challenges for firms providing such services.12 13 Firstly, without a clear mechanism to profit from these services, are they able to scale fast enough to make a significant difference to advertising-supported ‘free’ platforms with billions of users? And secondly,with the global content-moderation industry projected to reach $8.8bn in 2022,14 with Facebook employing tens of thousands of moderators and sophisticated machine-learning systems, is it feasible for small firms to provide such services?

As Keller notes, there are options for smaller providers to prioritise the types of content that are of most interest to their users, and to share the burden of assessing content – although this risks a homogeneity of subjective assessments, reducing the benefits of this whole approach for freedom of expression. We already see such collaboration in the tech industry-funded Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism. Twitter’s Nick Pickles has suggested governments consider requiring large platforms to make available their tools for identifying ‘harmful’ content, such as hate speech, to smaller firms.15

One option would be for civil-society groups to provide such services as part of their membership programmes, possibly supported by philanthropic organisations; and for some of the data to be crowd-sourced. At a smaller scale, civil-society groups could develop detailed curation settings to overlay large platform services, such as Facebook, if those companies were required to support them, avoiding the costs for civil society of providing real-time, human curation services. For example, a free speech organisation such as ARTICLE 19 could develop settings their supporters could choose for Facebook content moderation, which maximised open debate and discourse. A faith community might develop settings relating to moderation of religious content. Users could be prompted when they sign up to incumbent social-media services as to which curation service they wished to use.

In another model, crowd-sourced curation by community groups in federated social-media services such as the Twitter-like Mastodon (shown in Figure 3) can support community ownership of content-curation decisions, while reducing their individual impact compared to decisions affecting potentially billions of users on a global platform.

For widely illegal content, such as child sexual-abuse material, organisations including the US National Center for Missing and Exploited Children maintain ‘hash lists’ of known, illegal material that can be checked by platforms. And a number of governments report these and other types of content they have identified as illegal to platforms. (External scrutiny of these reports is important to ensure they are accurate and proportionate.) In assessing the desirability of a federated solution, it’s worth noting that it would be less easy for illegal content to be suppressed across a diverse ecosystem of services than in centralised, concentrated systems.

A more radical measure would be to require the largest firms to share advertising revenues relating to the use of alternative curation systems – or even to require the unbundling of service provision from the systems’ advertising-based funding,16 which could enable users to choose from advertising platforms with different approaches to profiling and privacy, or to pay directly, with the option to pay separately for a social-media service and a curation system.

What safeguards are necessary to ensure that interoperability respects rights?

It is important to note that ‘frictions’ in gathering user data have played an important role in the past in practical protection of privacy. Since interoperability can reduce these frictions, it means regulatory enforcement of data-protection principles will become even more important. Cyphers and Doctorow note: ‘To the extent that the tech companies are doing a good job shielding users from malicious third parties, users stand to lose some of that protection.’17

Keller, Maréchal and others have also noted that careful attention is needed to ensure interoperability remedies and greater modularity do not have a negative impact on user privacy. This is particularly the case for data relating to users’ contacts rather than themselves, since users cannot consent to the processing of their contacts’ data.

Arguably, specific provisions in the GDPR (listed below) could comprehensively cover interoperability in Europe, and there are over a hundred other countries with similar comprehensive privacy laws; ‘the existence of the GDPR solves the thorniest problem involved in interop and privacy. By establishing the rules for how providers must treat different types of data and when and how consent must be obtained and from whom during the construction and operation of an interoperable service, the GDPR moves hard calls out of the corporate boardroom and into a democratic and accountable realm.’18 And in jurisdictions without such legislation (notably the United States), privacy protections can be included in legislation enabling interoperability.

The most important relevant principles in the GDPR and similar laws are explicit user consent, data minimisation18 and purpose limitation. With explicit user consent, users would be in full control of interoperability features, with meaningful information provided about the privacy and security consequences before enabling them. (The UK’s Open Banking programme, which allows personal and small business current account customers of the UK’s nine largest banks to authorise third-party services to access their account records and make payments, chose to require explicit consent for all interoperability functions, to build user trust).20

Data minimisation means the minimum personal data needed for a task should be collected. Purpose limitation means a company should process data only for the purposes for which it was collected (or in the case of less sensitive data, ‘compatible’ purposes). The GDPR also requires that technical systems preserve data-protection rights by design and by default (Article 25), and ensure ‘appropriate security of the personal data, including protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organisational measures’ (Article 5(1)(f)).

If interoperability was enacted consistently with the GDPR, a user of one social media service who had become ‘friends’ with the user of another, interoperable service, should receive status updates and other content shared by their ‘friend’ but not any other information from that service. That user may also be able to see the number of times an update has been ‘liked’, but not the identities of the users of the second service who have done so. And the user’s social media service should likewise process information from the ‘friend’ solely for the purpose of facilitating interoperability – not, for example, for creating an advertising profile of the friend. Cyphers and Doctorow suggest the first service might also be required to ‘serve as a ‘consent conduit,’ through which consent to allow… friends to take data with muddled claims with them to a rival platform can be sought, obtained, or declined.’18

A more data-focused example is where a user is enabling one service to access their customer records on a second service – for example, to let a mortgage provider assess their monthly current account activity. The access should be limited in relation to data about other natural persons in their transaction history, while the mortgage provider should not be allowed to build a user profile based on the data it has accessed unless the user explicitly consents to this. A related example is given by the German consumer protection union, VZBZ: ‘a provider who certifies the freedom from rent debt by regularly debiting rental payments does not need access to cancellations from the trade union, the party or the fertility clinic (examples of data of a special category according to Article 9 GDPR).’22

Interoperability: not a risk-free endeavour

There is the risk that Big Tech firms could use the veil of interoperability to justify processing large volumes of user data for relatively trivial purposes, such as targeted advertising. Campaigner and researcher Wolfie Christl has noted: ‘Mandating personal data interoperability can make sense, but without strictly enforced limits and considering the political economy of data it will lead to yet another cesspool of data exploitation by both small and large firms.’23

Cyphers and Doctorow add: ‘Interoperability without privacy safeguards is a potential disaster, provoking a competition to see who can extract the most data from users while offering the least benefit in return… Having both components – an interoperability requirement and a comprehensive privacy regulation – is the best way to ensure interoperability leads to competition in desirable activities, not privacy invasions.’

Where regulators wish to impose large-scale data access provision on a large firm, these privacy considerations are even more important. Where possible, access should only be given to aggregate statistics about data, or machine-learning model parameters.

As far as possible, any access to raw data should be only to pseudonymised data – in other words, with information explicitly identifying individuals (such as names, dates of birth and addresses) removed. However, because any detailed information about individuals can often be linked with other data sources to reidentify or link it back to them, regulators will need to carefully consider what is the minimum amount of personal information needed, and what technical measures (such as differential privacy) can be applied to ensure these limits are not breached.24 In all these cases, baseline privacy requirements such as data minimisation and purpose limitation should continue to apply.

However, looked at another way, interoperability could provide strong market-driven, retention incentives to companies to improve user privacy, both generally by increasing competition and the ability of privacy-sensitive customers to switch services, and specifically by supporting users to choose more privacy-friendly components of services (such as a personal data store running sandboxed analysis apps), where such modularity has been enabled.

How have interoperability remedies been used?

Interoperability remedies have been used under existing competition laws in some of the key cases of the digital era: preventing Microsoft from locking competitor browsers out of Windows,25 and more recently requiring Google to make it easier for European Android users to choose an alternative default search engine26 and for specialised search engines to feature in search results.27 The slow pace of competition enforcement has also encouraged policymakers in the US, Europe, India, Australia and elsewhere to develop explicit, up-front rules imposing interoperability on the largest technology and financial services companies.28

These rules show great potential in reversing the trend over the last fifteen years towards ever-larger digital conglomerates dominating a range of key digital markets in many countries – ‘an approach focused on creating a more vibrant and diverse ecosystem of smaller digital applications, technologies and infrastructures.’ Siddarth and Weyl highlight the positive model provided by Taiwan’s g0v programme, with common ‘social communications protocols, data and compute sharing infrastructure, open source software, identity and payments standards, and large machine learning models trained on data created in a Creative Commons framework.’ This will become ever-more important as software continues ‘eating the world’ by becoming a core part of a growing number of industries, such as the automotive sector.

Careful analysis of platforms’ business models and individual services is needed to design optimal interoperability remedies. But the effort is worth serious consideration: they could enable the emergence of an Internet that allows individuals to control much better the use of their personal data via their own personal data store; to choose freely from a range of interoperable services, including social media, instant messaging, video sharing and search engines; and to replace key common components of these services, such as identity management, cloud storage and curation engines. This would support a much greater diversity of services and service providers, rather than the near-monoculture we see today, promoting individual autonomy and incentivising businesses to better meet the needs of their users.

This is the second in a series of posts from Ian Brown, a leading specialist on internet regulation and pro-competition mechanisms.

The first explores how interoperability could be the key to addressing platform power. Read From ‘walled gardens’ to open meadows.

Image credit: Malik Evren

- Crawford et al. (2021). ‘Equitable Interoperability: The “Super Tool” of Digital Platform Governance’. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3923602

- Competition & Markets Authority. (2016). Retail banking market investigation: Final report. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57ac9667e5274a0f6c00007a/retail-banking-market-investigation-full-final-report.pdf

- Competition & Markets Authority. (2019). Online platforms and digital advertising: Market study final report. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5fa557668fa8f5788db46efc/Final_report_Digital_ALT_TEXT.pdf

- Conseil national du numérique. (2020). Concurrence et régulation des plateformes: Étude de cas sur l’interopérabilité des réseaux sociaux. Available at:https://cnnumerique.fr/files/uploads/2020/2020.07.06.ra_cnnum_concurrence_web.pdf

- ARTICLE 19. (2021). Taming Big Tech: Protecting freedom of expression through the unbundling of services, open markets, competition, and users’ empowerment. Available at: https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Taming-big-tech_FINAL_8-Dec-1.pdf

- Andersdotter, A. ‘Framework for studying technologies, competition and human rights’. Amelia Andersdotter. Available at: https://amelia.andersdotter.cc/osi_and_humanrights/tech_osi-competition-human-rights_framework_v2.pdf

- Mali, S. (2021). ‘Understanding Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) From The Basics’. STL. Available at: https://www.stl.tech/blog/understanding-o-ran-from-the-basics/

- FreedomBox is a private server for non-experts: it lets you install and configure server applications with only a few clicks. It runs on cheap hardware of your choice, uses your internet connection and power, and is under your control. See: https://www.freedombox.org

- Siddarth, D. and Weyl, E. G. (2021). ‘The case for the digital commons’. World Economic Forum. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/the-case-for-the-digital-commons/

- Inverardi, M. (2021). ‘German court turns to top European judges for help on Facebook data case’. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/legal/german-court-turns-top-european-judges-help-facebook-data-case-2021-03-24/

- Holmes, S. et al. (2020). ‘Competition Policy and Environmental Sustainability’. International Chamber of Commerce, The World Business Organization. Available at: https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/12/2020-comppolicyandenvironmsustainnability.pdf

- Keller, D. (2021) ‘The Future of Platform Power: Making Middleware Work’. Journal of Democracy. Available at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/the-future-of-platform-power-making-middleware-work/

- Fukuyma, F. (2021). ‘The Future of Platform Power: Solving for a Moving Target’. Journal of Democracy, vol. 32, no. 3, July 2021, pp. 173-77. Available at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/the-future-of-big-tech-solving-for-a-moving-target/

- Satariano, A., and Isaac, M. (2021) ‘The Silent Partner Cleaning Up Facebook for $500 Million a Year’. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/31/technology/facebook-accenture-content-moderation.html

- Pickles, N. (2020). 18 February. Available at: https://twitter.com/nickpickles/status/1229577370220130304?s=21

- Davies, T., and Georgieva, Z. (2021). ‘Zero Price, Zero Competition: How Marketization Fixes Anticompetitive Tying in Monetized Markets’. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3868332

- Cyphers, B., and Doctorow, C. (2021) ‘Privacy Without Monopoly: Data Protection and Interoperability’ Electronic Frontier Foundation. Available at: https://www.eff.org/wp/interoperability-and-privacy

- Cyphers, B., and Doctorow, C. (2021).

- Cyphers, B., and Doctorow, C. (2021).

- Competition & Markets Authority. (2016).

- Cyphers, B., and Doctorow, C. (2021).

- Verbraucherzentrale (2021). Privatsphäre bei digitalen Finanzdienstleistungen schützen. Available at: https://starke-verbraucher.de/sites/default/files/downloads/2021/04/01/210324_position_psd2.pdf

- Christl, W. (2021). 19 January. Available at https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1351634600049651713.html

- de Montjoye, Y-A., Taquet, M. (2019). ‘Anonymity Takes More than Protecting Personal Details’. Nature. 574, no. 7777 (8 October 2019): 176. Available at https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03023-3

- European Commission. (2009). COMMISSION DECISION of 16.12.2009 relating to a proceeding under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/cases/dec_docs/39530/39530_2671_5.pdf

- European Commission. (2018). COMMISSION DECISION of 18.7.2018 relating to a proceeding under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (the Treaty) and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement (AT.40099 – Google Android). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/cases/dec_docs/40099/40099_9993_3.pdf

- General Court of the European Union. (2021). Judgment in Case T-612/17 Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping). Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2021-11/cp210197en.pdf

- Brown, I. (2021). ‘Recent developments in digital competition’. Ian Brown. Available at: https://www.ianbrown.tech/digital-competition-briefing-1/

Related content

From ‘walled gardens’ to open meadows

How interoperability could be the key to addressing platform power

Beyond the regulation of big platforms – supporting different visions for digital ecosystems

An introduction to the Rethinking data programme

Rethinking data and rebalancing digital power

What is a more ambitious vision for data use and regulation that can deliver a positive shift in the digital ecosystem towards people and society?

Rethinking data: working group for data regulations

An interdisciplinary and international group of experts to advise on the development of data governance and regulations