Can digital immunity certificates be introduced in a non-discriminatory way?

New forms of technology are coming. How do we ensure they’re deployed in a way that conforms to equality regulation?

8 October 2020

Reading time: 10 minutes

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused revolutionary changes to working practices, but how do we judge whether these are legal or illegal?

One major change is the increasing use, by employers wanting to encourage staff to return to work, of new forms of technology aimed at securing a safe working environment. Many of these systems automatically grant (or refuse) access to services and workplaces, and have received significant press interest.

One type of technology, deployed by governments and employers, uses ‘digital immunity passports’ or ‘digital immunity certificates’ to identify individuals with or without COVID-19 antibodies in their blood. Questions are now being asked as to whether these tools are lawful. In this post, we consider their legal implications.

How can technologies be used to tackle COVID-19?

We start with a basic obligation on employers: they are under a statutory, contractual and common law duty to provide a safe working environment. There is also a more specific obligation on employers under the Equality Act 2010 (EA 2010) to make reasonable adjustments to the working environment in order to protect disabled employees and enable them to participate on an equal footing.

There is no doubt that there are some excellent and useful technological products, designed to identify who might have COVID-19 or be vulnerable to infection, which help employers fulfil these obligations, for example, we know that:

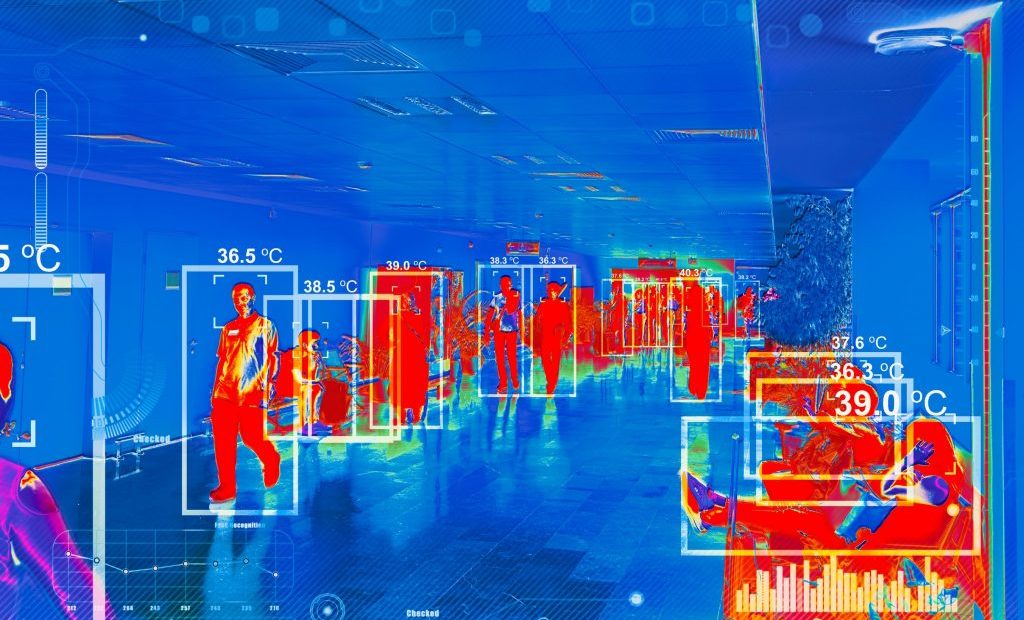

- thermal cameras are being used to monitor workers’ body temperatures

- breathing monitors are being advertised as a means of analysing whether employees are experiencing shortness of breath – another possible indicator of COVID-19

- contact tracing tools are being deployed that monitor which workplace areas infected employees have visited and the people they have met, with a view to increased sanitisation

- machine learning algorithms have been developed that can analyse employees’ personal data, such as medical history, to determine which members of staff are most vulnerable to COVID-19, and so which are in greatest need of protective measures.

But there is another angle here. Some technology systems have been developed that could expose employees to adverse consequences, such as disciplinary action or even dismissal for breaking new rules around social distancing and the reduction of infection. For example:

- wearable devices, known as personal motion systems, that buzz when the wearer is less than two metres away from someone else

- hygiene tracking solutions that can determine whether an employee has washed their hands for over 20 seconds

- video analysis systems that can alert an employer if workers are too close together or not wearing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

Digital immunity passports and digital immunity certificates fall in the middle: they can both help and hinder employees. We know that governments, employers and companies have started to explore tools whereby a device is used to signal that the owner has COVID-19 antibodies in their blood. In a work context, the perceived benefit is that staff could feel more confident returning to the workplace knowing that they may be ‘immune’.

This sounds like a ‘win-win’ situation for employee and employer alike. But, creating a mechanism by which an employer can assess who is ‘safe’ or ‘safer’ may, in turn, have negative consequences – for example barring people from the workplace. It is this more problematic side to digital immunity certificates that we explore below.

The principle of non-discrimination

The first point to make is that there are numerous, significant discrimination angles to employers, or indeed any organisation, using digital immunity certificates in the wrong way. The most obvious angle is disability. Many disabled people will have needed to shield or avoided or minimised their contact with populated places, whether workplaces or supermarkets. Therefore they may well be less likely to be able to demonstrate that they have COVID-19 antibodies. There may be similar patterns that emerge in relation to other protected characteristics, such as age or race.

In so far as there is a link between certain protected characteristics (age, race, disability) and COVID-19 antibodies, then limiting people’s ability to return to work or access facilities and services through the use of immunity passports might amount to indirect discrimination under the Equality Act 2010. We stress the word might. If protected groups are disadvantaged by the use of immunity passports, a claim of indirect discrimination can always be defended on the basis that the employer is pursuing a legitimate aim and the use of immunity passports is a proportionate means of achieving that aim (s.19 (2)(d) Equality Act 2010).

It follows that the success of any claim will likely depend on what an employer or organisation is trying to achieve by deploying immunity passports, how effectively they achieve those aims and the proportionately of their actions. We can illustrate these points by positing two hypothetical scenarios.

Scenario 1: Discriminatory use of digital immunity certificates

Let’s imagine a large shop that has struggled during lockdowns with reduced sales. It needs to cut its workforce and decides, as part of a redundancy process, to dismiss employees who can’t demonstrate that they have COVID-19 antibodies. The employer believes that having as many employees with COVID-19 antibodies as possible in its remaining workforce will minimise sickness absence in the future and make shoppers feel safe (hence inducing them to shop more).

Now, if, as a result of that redundancy exercise, the employer ends up with a workforce which is predominantly younger, non-disabled and from certain ethnic groups, it can readily by seen that the employer might face a claim for indirect discrimination from protected groups who have been dismissed, e.g. older workers. Would such a claim succeed?

The employer is probably pursuing legitimate aims (seeking to minimise sickness levels and encouraging more shoppers). But the shop may face real difficulties demonstrating that its actions were a proportionate means of encouraging shoppers to feel safe and reducing sickness absence since:

- There are concerns that COVID-19 antibodies might not grant immunity forever or indeed prevent the spread of infection, so it is not clear that immunity certificates will achieve the employer’s aims.

- There are less intrusive and non-discriminatory ways of achieving the employer’s aims of reducing infection and illness, such as mandating the use of masks, making hand sanitiser available, enforcing social distancing, improving ventilation, etc. than dismissing employees on the basis of their health status.

Accordingly, we think that there is a real risk that digital immunity passports or certificates will give rise to unjustifiable indirect discrimination in so far as they are used to determine employment status.

What’s more, the notion that employers might consciously or unconsciously prune their workforce during the pandemic, in a way that might disproportionately impact vulnerable groups, is not fantasy. In August 2020, the Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB) published a report: An unequal crisis: Why workers need better enforcement of their rights that reached the following alarming conclusions:

- 17% of the working population is facing redundancy

- 27% of disabled people are facing redundancy

- 37% of disabled people, where their disability has a substantial impact on their activities, are facing redundancy

- 39% of people with caring responsibilities are facing redundancy.

Moreover, at a recent event hosted by the Ada Lovelace Institute on 29 July 2020, Katie Jacobs, Senior Stakeholder Lead at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development explained that, at a recent forum for Chief Human Resources Officers, a senior leader had queried whether staff could be prioritised for return to the workplace, following furlough, on the basis of antibody test results, so that ‘immune’ staff could be more quickly reintegrated.

Scenario 2: Non-discriminatory use of digital immunity certificates

At the other end of the spectrum, there might well be situations where it would make perfect sense to take into account an employee’s potential immunity when making decisions that impact on employment.

Imagine a specialist surgeon is required for a lifesaving operation that must happen on a particular day, to coordinate with other important medical procedures. It might be very important to choose a surgeon who has COVID-19 antibodies over an equally skilled surgeon who can’t demonstrate possible immunity, to minimise the risk of the operation being cancelled. Here, the employer who priorities the surgeon with antibodies over the surgeon without antibodies would be pursuing a legitimate aim (protection of the health of a patient) and doing so in a proportionate way, since there is no immediate tangible disadvantage to the surgeon who is ‘overlooked’ on this particular occasion1.

Future regulation?

Of course, these scenarios are extreme but show the uncertainties around the use of immunity passports and the many considerations to bear in mind in order to foster a nuanced debate.

Once we move beyond the workplace, the balancing exercise will also shift. For example, banning access to a flight on the basis of antibodies testing would be less onerous to an individual than taking away their livelihood. This will be highly relevant when it comes to considering proportionality.

Since we are clear that technology and AI can bring benefits both in the workplace and beyond, we are troubled by the lack of clear guidance from the UK Government as to the acceptable and unacceptable uses of these tools by employers, public authorities and commercial bodies from the perspective of the principle of non-discrimination and the duties created by the Equality Act 2010. We are also concerned that policing these new forms of technologies may fall on to workers through the medium of litigation, in the absence of strategies to prevent harm occurring in the first place.

Here are some ideas for tools that the UK Government could deploy:

- Compulsory and publicly available assessment of new forms of technology for risks, including discrimination. This is not a new idea. Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) are well established as a means of auditing compliance with the law. It has been recommended that a similar approach to compliance with equality law should be undertaken and the results placed in the public domain. This would certainly constitute an additional safeguard.

- Certification schemes by independent third parties. Interestingly, in the UK, the use of certification marks as a means of regulating the use of invasive technologies is common. The Surveillance Camera Commissioner operates a certification scheme that enables organisations to demonstrate that they comply with the surveillance camera code of practice. There is also a self-certification scheme for the manufacturers of surveillance systems and components in order to demonstrate that security has been adequately addressed with the design of products. A certification scheme would allow technology to be pre-approved before any harm has arisen.

- Statutory guidance drafted by relevant regulators, like the Equality and Human Rights Commission, which spells out precisely how technology can and cannot be used to provide certainty to business and protection for the public.

In summary, we think that:

- using technology to limit workplace access could be unlawfully discriminatory, but

- the lawfulness of such systems is highly fact-specific.

This means great care is needed. We do not think that these technologies should be simply ruled out, because we are also clear that, if used properly, they can be positive for both employers and employees. However, we think that the lack of legal certainty poses a dilemma which the UK Government must address head-on. The aim should be to provide clear regulatory standards, spelling out how this kind of technology can be deployed appropriately. Only this path will enable these technologies to fulfil their promise to help tackle the pandemic.

In short, we believe that additional creativity and thought is needed. New forms of technology are coming. They will be deployed. What is needed now is a public debate about their acceptability and clear strategies to ensure that discrimination does not occur.

For more information about how technology, and in particular AI, can lead to discrimination take a look at AI Law, a resource created and maintained by the authors.

Image credit: sefa ozel

Related content

International monitor: vaccine passports and COVID-19 status apps

A tracker collating developments in policy and practices around vaccine certification and COVID-19 status apps as they emerge around the world.

Public health identities in the private sector

The third in our series of events addressing the nascent ‘public health identity’ systems developing around the world

Something to declare? Surfacing issues with immunity certificates

As the building of technical capacity for immunity apps and deliberation about deployment progresses, we surface six issues policymakers must consider

A rapid online deliberation on COVID-19 technologies: building public confidence and trust

Considering the question: ‘What would help build public confidence in the use of COVID-19 exit strategy technologies?’