Seizing the ‘AI moment’: making a success of the AI Safety Summit

Reaching consensus at the AI Safety Summit will not be easy – so what can the Government do to improve its chances of success?

7 September 2023

Reading time: 10 minutes

Introduction

The current ‘AI moment’ is a critical inflection point for the UK and the world. As AI systems become more complex and capable, organisations across all sectors of the global economy are looking to develop, deploy and make use of their potential to benefit people and society.

With this opportunity come considerable risks: ranging from bias, misuse, and system failure to structural harms, such as the concentration of economic power in the hands of a small number of companies.

Without concerted action, we may unwittingly lock ourselves into a set of technologies and economic dynamics that fail to benefit people, communities, or society as a whole.

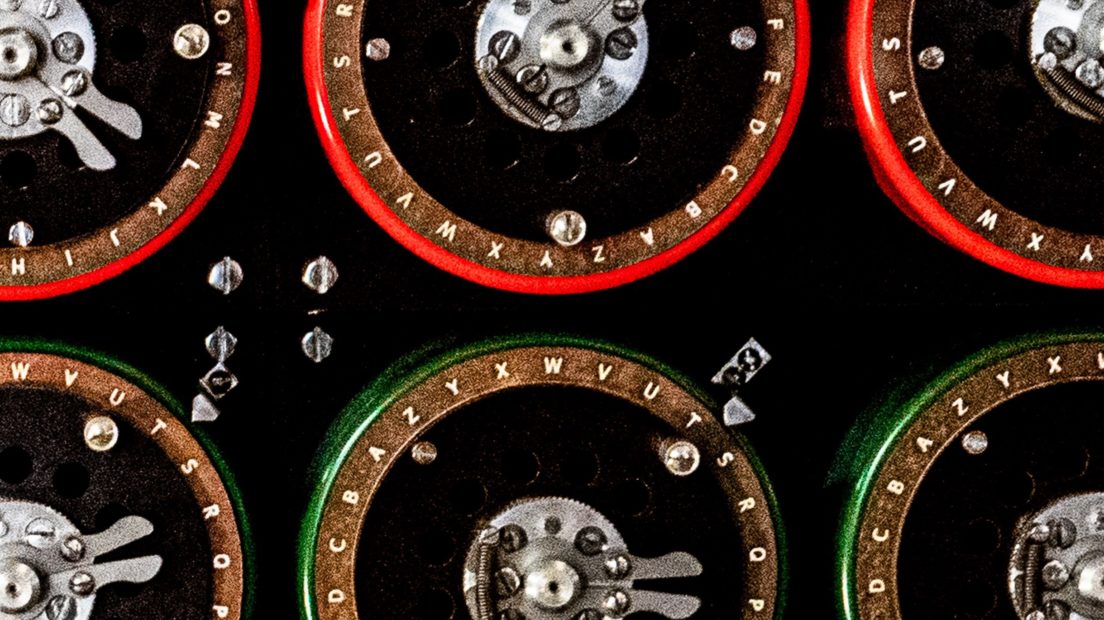

Enter the UK Government, which is hosting an ‘AI Safety Summit’ on 1 and 2 November at a venue synonymous with overcoming wicked technical problems: Bletchley Park, where Allied codebreakers deciphered the German ‘Enigma’ code during World War II.

The Government has recently set out objectives for the Summit, including reaching a ‘shared understanding’ of AI risks, agreement on areas of potential international collaboration and showcasing ‘AI for good.’

Reaching consensus on these topics will not be easy – so what can Government do to improve its chances of success?

Aim for a broad definition of ‘AI safety’

The Summit is being framed around ‘AI safety’ – but this is not an established term, and there is little agreement on what risks this covers. There are many typologies of AI risks and harms (an active area of research for Ada), but one way of thinking is to group them into four broad categories:

- accidental harms from AI systems failing, or acting in unanticipated ways, such as self-driving car crashes, or discrimination when sifting job applications.

- misuse harms from AI systems being used in malicious ways, such as bad actors generating misinformation using ‘generative’ AI applications such as ChatGPT and Midjourney.

- supply chain harms from the processes and inputs used to develop AI, such as poor labour practices, environmental impacts, and the inappropriate use of personal data or protected intellectual property.

- structural harms from AI systems altering social, political, and economic systems, such as the creation of unequal power dynamics (for example through market concentration or inequitable access to AI systems), or the aggregate effect of misinformation on democratic institutions.

All of these types of harms could reasonably be considered in scope for a global ‘AI safety’ regime. The idea of ‘safety’ is employed in other important domains – like medicines, air travel and food – to ensure that systems and technologies enjoy public trust (‘Do I feel safe to take flights?’), and that they protect core values that we care about (‘Will food stay affordable?’). AI increasingly forms a core part of our digital infrastructure, so our concept of AI safety will need to be similarly broad.

In some cases, AI harms are well-evidenced – such as the tendency of certain AI systems to reproduce harmful biases – but in others they are difficult or impossible to prove. These include, for example, the potential for mass unemployment resulting from AI-enabled job automation or augmentation, or claims that powerful AI systems may pose extreme or ‘existential’ risks to future human society.

A narrow definition based primarily on extreme risks would in practice place all existing AI systems out of scope of international governance efforts, and focus discourse and resource only on challenges that remain speculative. This would mean ignoring the overwhelming evidence that current AI systems are capable of, and – in many cases– already causing significant harm.

Keep a wide variety of AI systems in scope

The AI Summit has also increasingly spotlighted ‘frontier AI’ as a priority. This can be convenient shorthand for systems with newer, more powerful, and potentially dangerous capabilities. Investment in understanding cutting-edge systems – as represented by the newly-renamed ‘Frontier Model Taskforce’ – is welcome, given the opacity of much leading industry research, and the need for independent, public-interest alternatives.

Policymakers should however be mindful that there is no agreed way of determining whether a model is ‘frontier’ or not, and some industry figures have claimed that no currently deployed AI models qualify as frontier. Coupled with the fact that a frontier is necessarily a moving horizon, this creates a poor target for regulation.

Our research suggests that risks from AI do not simply grow in proportion with the technical capabilities of a given system, but depend intimately on the contexts in which those systems are deployed. Existing systems with capabilities far behind the ‘frontier’ can produce unexpected harms when deployed in new contexts, particularly without prior testing or consultation with users and other affected parties.

Narrow, technical definitions of AI safety – those that focus on whether an AI system operates robustly and reliably in lab settings, ignoring deployment context and scoping out considerations like fairness, justice, and equity – will therefore fail to capture many important AI harms or to adequately address their causes. The Summit should instead build consensus around an expansive definition of safety that covers the full range of harms arising from diverse types of AI systems.

This need not be a zero-sum game: the essential building blocks of any credible AI safety regime – such as pre-release and pre-deployment testing of systems, greater accountability for key actors in the value chain and the involvement of diverse publics in decision-making – are likely to support the management of a variety of different AI risks. At this nascent stage in the development of common approaches to global AI governance, it would unnecessarily constrain the development of these solutions to scope them around narrow and overly technical definitions of risk.

Centre the perspectives of affected people and communities

Breaking the Enigma cipher was a technical challenge that required world-leading cryptographical expertise and significant government backing. Governing AI effectively is however a sociotechnical challenge: one that requires the meaningful involvement of people and communities, particularly those most affected by the development and use of AI systems.

This is particularly true given the differential impacts of AI harms on different social and demographic groups. Certain AI harms are likely to have significant effects on particular social or demographic groups, with others left untouched or even benefitting. For instance, the proliferation online of highly realistic ‘deepfake’ porn has negative impacts which overwhelmingly accrue to women; while poor labour practices in the AI supply chain predominantly affect low-income workers in the Global South.

The question of which harms are most ‘significant’ depends therefore on the vantage point from which one is considering the question of safety: safety for whom, and from what? If the perspectives of people and groups affected by AI are not centred in global AI governance, then important harms could be overlooked or deprioritised – or solutions could be proposed that might lead to unacceptable trade-offs or further problems down the line.

National and international civil society organisations – including consumer groups, trade unions and organisations representing marginalised groups, and particularly those based in the Global South – have a crucial role to play in surfacing these perspectives. They should be involved in the Summit and – in the longer term – in any institutions or treaty processes aimed at establishing global governance mechanisms for AI.

This could entail a formal policy-setting or scrutiny role. There are several precedents for this, including:

- the United Nations Climate Change conference (commonly referred to as ‘COP,’ or ‘Conference of the Parties’), which defines non-governmental organisations, indigenous peoples, trade unions and other groups as ‘constituencies’ and formally involves them in scrutiny

- the International Labour Conference, which brings together governments, employers, and trade unions to decide the policies and standards of the International Labour Organisation, a United Nations agency

- the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, in which communities and civil society hold voting seats on the Board.

These examples are not exhaustive and best practice is still developing: many would argue that these structures give civil society organisations too little power or oversight, or that their overall effectiveness has been limited. Nevertheless, they offer potential models for genuine multistakeholder engagement that the Summit could build on.

Follow concrete interim commitments with legislation

History is littered with examples of seemingly ambitious international agreements that were met with great fanfare, but undercut by poor implementation. Whether the Summit ultimately succeeds or not will be determined by whether it supports tangible change to the ways AI is developed, deployed, and used across the world.

Many AI harms are best dealt with at the development stage. This stage can be challenging for national governments and regulators to influence: leading AI developers are concentrated in a small number of jurisdictions, and detailed information on their models and development practices is often withheld. A priority for the Summit should therefore be agreeing measures to improve the accountability of these organisations and transparency of their systems.

At Ada we are continuing to investigate how this can be done, and our extensive research to date suggests that important first steps could include the introduction of:

- mandatory documentation, reporting, and transparency requirements for developers of foundation models, including information such as the computing resources and data used to train models, results from in-house audits and supply chain data, all of which could be required to be made available in a standardised form to governments and regulators from participating countries

- pre-release testing and evaluation requirements, accompanied by a high burden of proof on companies to prove their systems are safe

- support for third-party auditing and evaluation through the AI supply chain

- shared baseline standards for domestic regulation – and enforcement of that regulation as it applies to AI systems – in areas like intellectual property, human rights, and data protection law

- funding for work to develop standards, benchmarks and evaluations for capabilities and risks.

In the short term, some of these measures could be implemented through voluntary agreements with developers, building on welcome commitments made to both the UK and US governments by leading foundation model developers. It will however be vital that any such commitments are swiftly turned into mandatory requirements – perhaps through contract-based agreements with developers – and accompanied by a clear roadmap towards formal legal requirements with strong penalties for non-compliance.

Build towards long-term solutions

Government has recognised that a successful AI Safety Summit will be the first step in a longer journey – towards a future in which AI is safe and works for the benefit of people across the world.

For this year, focusing international government, research, and civil society expertise on a broad definition of AI safety would significantly strengthen our understanding of how to govern AI risks, and begin to build the necessary relationships and roadmap for future legislation. Delivering on this will be a challenging multi-year project, requiring sustained political will and the allocation of significant resources to implementation and enforcement.

In the longer term, it will be important to consider far-reaching policies that can rebalance power over AI towards people and communities. These might include pro-competitive interventions to address dominant industry players and improve access to models and data; global collaboration on public institutions for socially beneficial AI development and AI safety research; and the meaningful incorporation of the perspectives of affected communities into international regulatory institutions.

From the standpoint of today’s global AI ecosystem – characterised by inadequate governance, poor corporate accountability, and widespread abuses of power – this ideal of a more cohesive and strategic approach to international AI governance might seem distant. November’s Summit is an opportunity to bring it closer, to envisage – and make real – alternative AI futures in which these systems are made to work for people and society.

Related content

Regulating AI in the UK

Strengthening the UK's proposals for the benefit of people and society

Regulating AI in the UK

Recommendations to strengthen the Government's proposed framework

Regulating AI in the UK: three tests for the Government’s plans

Will the proposed regulatory framework for artificial intelligence enable benefits and protect people from harm?