Data stewardship: an archival perspective

Archives as datasets? What can we learn from archivists in data preservation and sharing?

12 November 2020

Reading time: 6 minutes

As a trainee archivist, I have frequently found myself over the last few years in attics and offices sorting through the files, folders and boxes of paper that make up archive donations to the library at Wellcome Collection, where I work.

The library regularly receives offers of archive material, which are surveyed to determine whether they fall within the scope of our collecting policy. Then, if the decision is made to acquire the material, a return journey is made to list, pack and transport it to offsite storage to await cataloguing.

Obviously, most of this work is now suspended due to COVID-19. But one example keeps coming to mind, as I’ve been thinking about the role of archivists in data preservation and sharing as part of my archive studies.

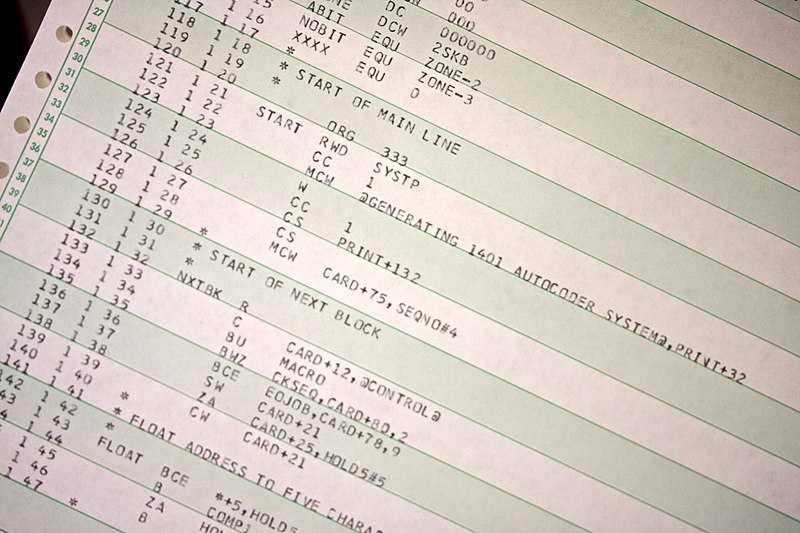

As a member of the team that surveyed and acquired the papers of perinatal epidemiologist and statistician Alison Macfarlane last year, I came across a great deal of raw data relating to her work on identifying risk factors for adverse health outcomes during pregnancy and early life, consisting of reams of paper containing raw figures and statistical analyses.

This kind of material could be of interest to contemporary epidemiologists seeking to understand how such risk factors have changed over time, as well as historical researchers seeking to understand the context and methodology of the original research. But we elected not to acquire this part of the collection; the library has limited space, which means we have to make decisions about what to collect and what not to collect.

Datasets generally fall outside of our collecting policy because we don’t have the skills or technical resources to manage them appropriately or to support researchers to access and interpret them – although, as in this case, we will suggest other repositories that may be better equipped to preserve this kind of material, such as the UK Data Archive.

As someone with a background in data management policy, from my time in the Wellcome Trust policy team, all of this has made me think about the role of archives and archivists in supporting data management and preservation for research and policymaking. Archivists are, after all, custodians of records – whether paper or digital – that provide evidence of individual or organisational activity for legal and official purposes, and which serve as sources of information that can be used in historical research.

Much has been written over the past two decades about the challenge of the transition to preserving predominantly digital records, which archivists and records managers are steadily getting to grips with through technological adaptation and new ways of working. This is necessary to prevent the digital ‘black hole’ of records being lost due to inadequate tools, obsolescence of formats, and the risk of organisations failing to embed the need for preservation into their records creation and management practices.

But less attention has been paid to the role of the archivist in the management and preservation of datasets, whether paper or digital: the role of ‘data archivist’ is still something of a specialism, requiring skills and expertise, whereas most archivists focus on ‘traditional’ paper and, increasingly, digital records. The earliest data archives established in the mid-20th century, including the UK Data Archive, had a focus on data from the social sciences, whereas data from the biomedical and physical sciences has tended to be managed by researchers themselves.

Issues resulting from this include highly localised and variable practices relating to data preservation and curation, making it difficult for other researchers to identify and access data that they might wish to reuse. There are also implications for the integrity and security of data, and a lack of consistency and common understanding of requirements for research data preservation presents difficulties for comprehensive data sharing strategies (as this research from Sweden demonstrates).

However, links between scientists, archivists and data managers are starting to be explored, amid a recognition that researchers and data scientists can benefit from archival perspectives and expertise, while archivists are understanding the importance of understanding scientific work, especially in universities and other research settings.

Archivists can bring expertise in systems, standards and formats for data preservation, drawing on the archival principles of provenance, original order, integrity, authenticity and accessibility, which are being increasingly employed in the digital realm.

Archivists can also bring perspectives on embedding these principles into recordkeeping systems, ensuring that records are captured and preserved from the moment of creation, rather than waiting until preservation becomes a priority – another necessary consideration in the digital world, where formats and systems can change and quickly become obsolete, by which time it can be too late.

Furthermore, archivists are already engaged in preserving the documentation of research activity as part of their core collections – this is what archivists at universities and specialist repositories like Wellcome do – but preserving datasets is arguably an area into which archival skills need to expand in the future, as they are already doing with digital records.

There is potential for archivists to think about documenting datasets as part of their historical scientific collections, either in collaboration with specialist data repositories with whom they may share common principles of information management, or by developing new tools and standards that enable them to develop their own expertise in data preservation.

Both these approaches would enable archivists, who as a profession are still broadly drawn from the humanities and social sciences, to develop confidence with the principles of scientific data generation and management. There is even a move towards thinking of archives as datasets, with the potential for manipulation and analysis using novel data mining tools as part of research projects.

The reason all this matters is the increasing proliferation of data – its collection, preservation, sharing and reuse – across all aspects of policy and public life. The value of sharing and reusing datasets to generate new research findings is a theme Wellcome has been exploring for some years, and has seen the development of initiatives like Wellcome Open Research and ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com to promote the rapid open access publication of research outputs, and the reuse of clinical datasets, respectively.

Much has been made of the potential of ‘big data’ to help tackle the big environmental and health challenges we face. But in doing so, we need to ensure that certain standards – of authenticity, integrity and accessibility – are in place to help us navigate the data deluge. The expertise of archivists can help with this, and ensure that data, along with the records of the activities that generated it, can be preserved for the long term.

This article is the final article in a series about data stewardship. Across the series researchers and practitioners working in different organisations and contexts, who each have a unique perspective on data stewardship, will share practical experience and research ideas.

It’s not possible or desirable for one person or organisation to decide what a ‘good’ use of data is. That’s why we hope this series and our research will help push forward thinking on how to govern data for good and ensure diverse voices contribute to defining it.

Let us know what you think – Tweet @AdaLovelaceInst using #DataStewardship or email hello@adalovelaceinstitute.org with Data Stewardship in the subject line.

Image credit: Marcin Wichary

Related content

Strength in numbers: a case study for building a data-based community in cystic fibrosis

Now, more than ever, data can be used to bring people together as well as numbers.

Working with the CARE principles: operationalising Indigenous data governance

Shifting the focus of data governance from consultation to values-based relationships to promote equitable Indigenous participation in data processes.

Common governance of data: appropriate models for collective and individual rights

From Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for governing the commons to mechanisms that ensure collective and individual data rights: what steps to take?

Practising data stewardship in India, early questions

How could data stewardship help to rebalance power towards individuals and communities?