Participatory and inclusive data stewardship

A landscape review

13 December 2024

Reading time: 242 minutes

Foreword by Reema Patel, Digital Good Network

This landscape report examines the evolution of participatory and inclusive data stewardship, tracing developments since the Ada Lovelace Institute’s early thoughts about Rethinking data[1] and the publication of the conceptual framework and analysis in Participatory data stewardship.[2]

Rethinking data drew attention to the substantial power dynamics inherent in data collection, use and management, which shape societal outcomes. It reinforces the central proposition that data is not, and cannot be treated as if it is, neutral. When we talk about data, we are also talking about the sociotechnical structures around how it is gathered and stored, and about power – who has the ability to influence outcomes around data, with agency and voice. We are always in the process of constructing data, and our relationship with it is dynamic and often unequal. Choices society makes about the production and use of data reflect the distribution of power and are conditioned by power asymmetries.

Central in my own thinking as a researcher in the early days of the Ada Lovelace Institute was what became the framework for data stewardship, grounded in economist Elinor Ostrom’s vision of a common-pool resource. Ostrom’s vision of a common-pool resource itself centres returning power back to the people to whom the resource relates. This demands that we see data itself as a shared resource that requires careful, inclusive and collective management. Ostrom’s early design principles on the commons emphasised that genuine stewardship must be inclusive and participatory, involving people and society as a whole to support common good.

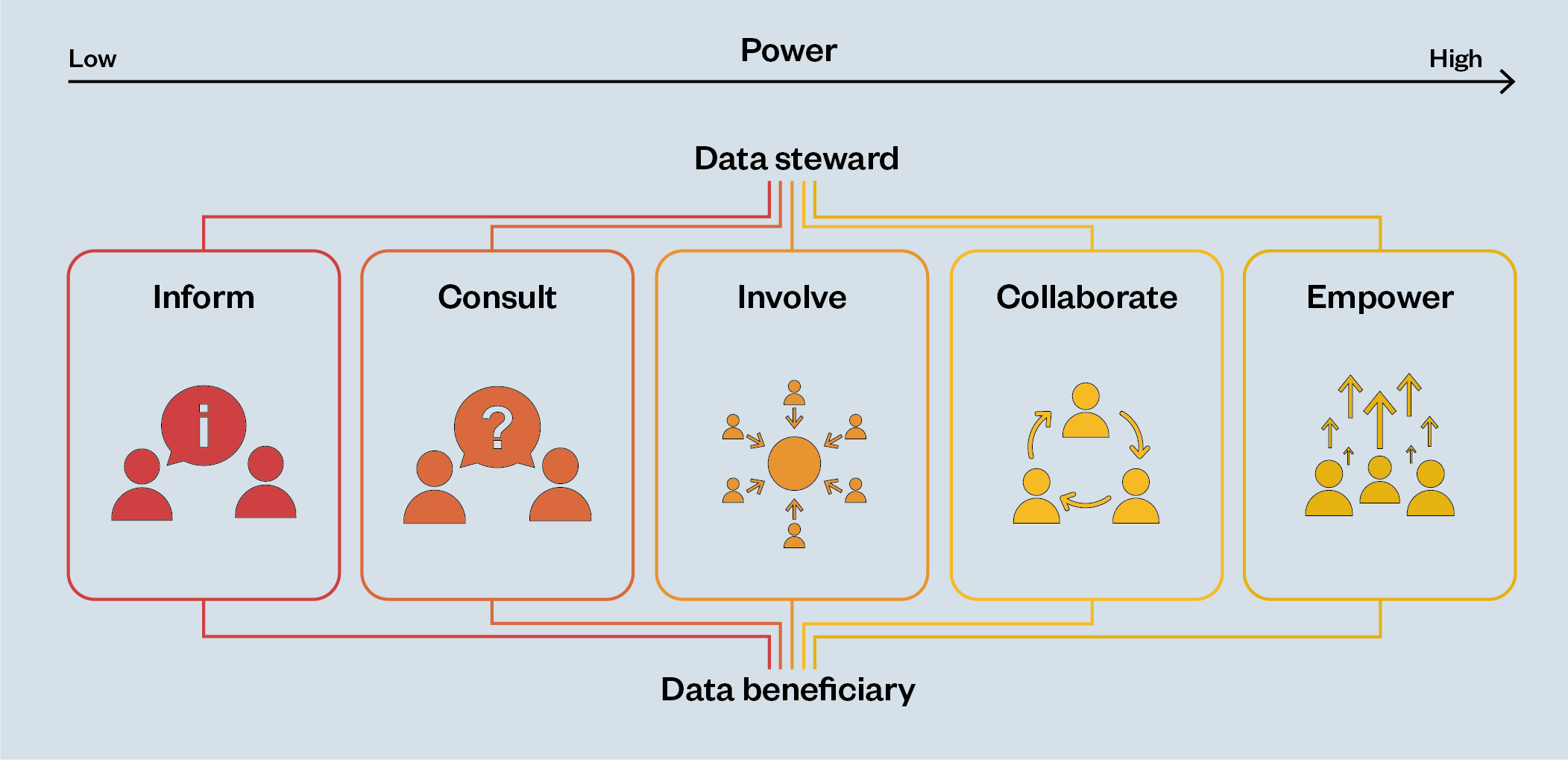

Participatory data stewardship extended this thinking into a structured framework based on Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation, advocating that participatory data practices should empower communities, shifting agency and control to citizens. Arnstein herself was a health policymaker based in the USA, and she observed the challenging dynamics of power and control between state, private actors and citizens first hand through her work as a policymaker in the health context.

Arnstein’s paper, ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’,[3] highlighted that the true value of participatory efforts lies in whether they successfully shift power structures and amplify marginalised people’s voices, enhancing their sense of agency and control. Inclusion and participation in her eyes are inextricably linked, with the most successful approaches ascribing a high level of agency and power to communities, and the least struggling to do so, or (even worse) reducing that agency or power – what she described as ‘tokenism’ or ‘manipulation’.

The Ada Lovelace Institute had since developed a programme of work exploring a positive vision for data, including a clear role for public participation. As innovation in the governance of data accelerates – especially and in light of the central role of data governance in shaping AI and its outcomes – it remains even more important that diverse communities and beneficiaries can influence data practices upstream, especially on issues where public opinion is unsettled.

This landscape review offers a timely reflection on the conditions that underpin participatory and inclusive data stewardship, as well as the developments – and the many obstacles – that characterise today’s landscape, especially given the post-pandemic surge in interest around participation in data and AI.

Looking ahead, the programme’s next publication will aim to provide practitioners and policymakers with actionable guidance and support for advancing inclusive and participatory data stewardship practices both in the UK and globally. It will also seek to offer renewed thinking on how best to assess the success, impact and effectiveness of their work as it evolves, recognising that this work rarely finishes. This reflects our commitment to building the field of participatory and inclusive data stewardship.

Reema Patel, Digital Good Network and Elgon Social Research

Principal Investigator, Participatory and Inclusive Data Stewardship

Executive summary

Data – that is, information about people and the world we live in – serves and supports many functions in society. Currently, data is foundational to initiatives that aim to improve people’s lives, from understanding the needs of local communities and collectives, to addressing significant societal and economic challenges, such as climate change or better health provision.

Governments, local authorities, institutions, private companies, civil society organisations, communities and groups of people therefore have aspirations to create, access, use and share data for different purposes. This means that they may all find themselves in a position where they are required to responsibly govern or ‘steward’ data.

There are considerable aspirations for data to support innovation, and economic and societal benefit. However, the current landscape is characterised by concentrations of data in silos and market dominance in a small number of multinational companies, and high-profile data-sharing errors and opaque private–public partnerships continue to undermine public trust in responsible data governance.

For example, the 2024 independent Sudlow review of the health data landscape makes the case for data to improve people’s lives – and the powerful insights generated by safely linking and analysing health data – but recognises significant structural obstacles and systemic delays that present barriers to maximising the benefits to society.[4]

This review, Participatory and inclusive data stewardship, builds on global scholarship and civil society analysis of practice, and specifically on three reports by the Ada Lovelace Institute (Ada) that interrogate the legal, structural and systemic preconditions required for data to deliver public benefit, and for people to make choices about their data.[5], [6], [7]

Ada’s working definition of data stewardship has been ‘the responsible use, collection and management of data in a participatory and rights-preserving way’.[8] The evidence provided in this review demonstrates the liveliness of debate around ‘data stewardship’ theory and practice. This encompasses multiple definitions and understandings of key terms – including data stewardship itself.

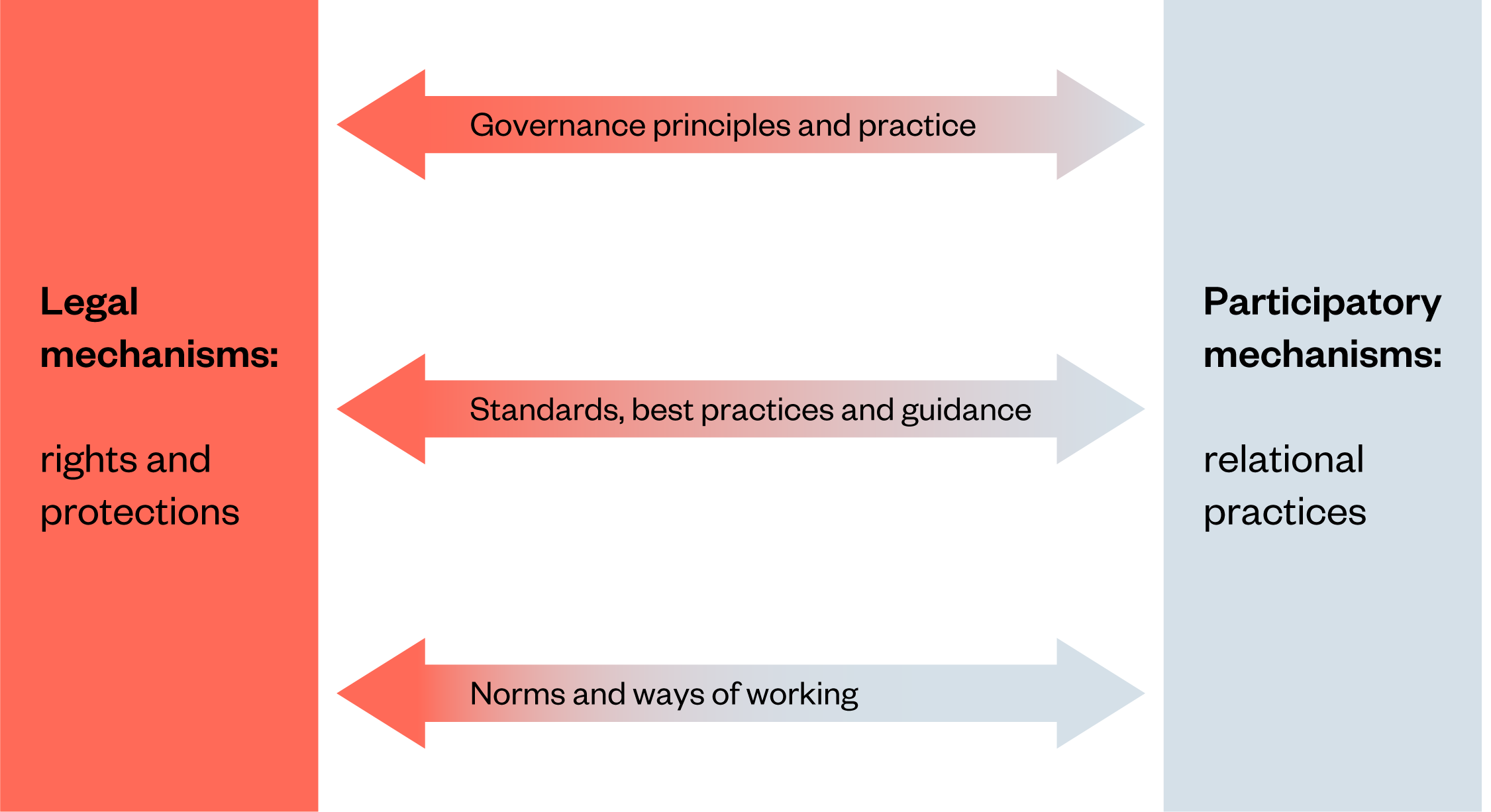

Participatory and inclusive data stewardship has two foundations: legal rights, responsibilities and established contractual and commercial law; and participatory practices and norms that are designed to increase participation and redistribution of power or agency. These can work together to achieve a range of stewardship purposes, including rebalancing power over data in the context of a data ecosystem that has become skewed towards large private-sector data holders.

This review also highlights where those two foundations can come into tension. On the one hand, governments are actively setting up new initiatives and partnerships that use the language of stewardship. In some examples, stewardship is primarily used to frame the stimulation and streamlining of data sharing, to foster innovation and mobilise data’s value for economic and societal benefit. At the same time, civil society and academic proponents are developing theory and practice around data stewardship’s capacities to support public benefit while rebalancing power towards data subjects and those affected by the use of data.

It provides an introduction to the utility of participation and inclusion in data stewardship, outlining the complexities of initiatives that require detailed knowledge of both legal mechanisms and participatory practices, and a snapshot of the landscape. As a landscape review, it preserves a neutral stance, while reporting on the perspectives of those working in this field on where and how the landscape has progressed over the years, and where there are still barriers and challenges that need to be addressed.

In particular, this review explores the role of inclusive practice in data stewardship and how this relates to participatory mechanisms. This is motivated by a recognition that – if data stewardship is to enable the potential for data to support societal, economic and environmental good – the distinct role of inclusion, in addition to participation, needs to be examined.

This review recognises that, for the debate to move forward, we need to understand where we are. To do this, it explores how data stewardship is being discussed and implemented, interrogating mechanisms that may facilitate participatory and/or inclusive practices, including the context of regulatory frameworks, and whether existing theory and practice is sufficient to meet the challenges of the current data ecosystem and the needs of data subjects and those affected by uses of data.

This review was produced as part of a joint programme of work with the Digital Good Network and the Liverpool City Region Civic Data Cooperative. The programme has been guided by the following research questions:

- What are the conditions across the ecosystem of participatory and inclusive data stewardship?

- Where are there distinctions across organisations working on participatory and inclusive data stewardship?

- How effective are various mechanisms for participatory and inclusive data stewardship?

The scope of this review focuses specifically on the first two research questions. The research sought to answer these questions through:

- Analysis of legal and participatory mechanisms that sets out the foundations of the landscape: the complex combination of existing legal provisions that ensure rights and protections and can underpin participation in data stewardship; and the practices that build out participatory and inclusive processes and outcomes.

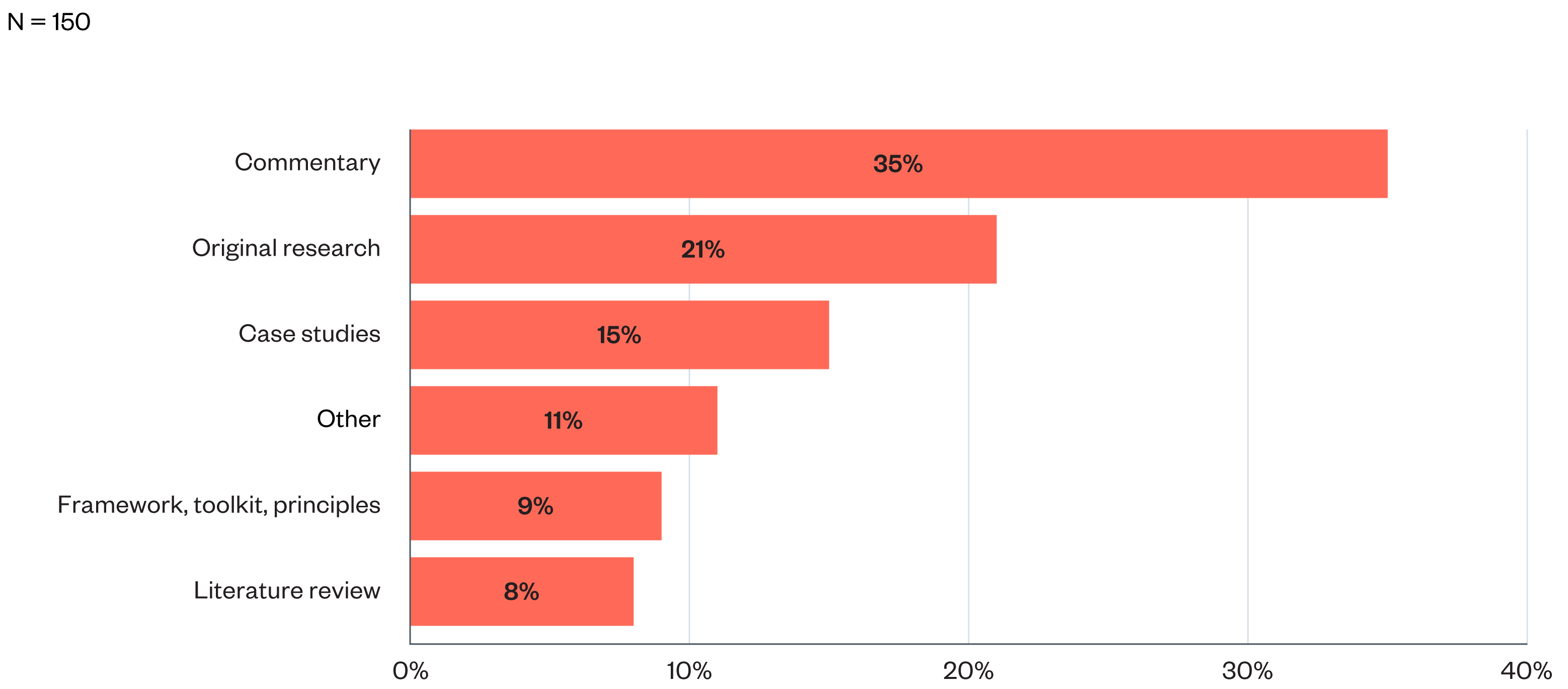

- A desk-based database review of current practices, using keywords related to stewardship, that provides a broad view across the landscape of intellectual and practical thinking from those already investing in participatory data stewardship mechanisms.

- Interviews with experts in the field of inclusive and participatory data stewardship that describe from their experience opportunities and advances in theory and practice, and where greater clarity is needed in order for participatory and inclusive data stewardship to deliver its potential.

The question of effectiveness requires detailed analysis of the significant proportion of data stewardship activity in practice surfaced by the desk-based data review. We describe some representative and novel examples, and provide data relating to those.[9] This research will be undertaken through a subsequent Digital Good Network project exploring participatory and inclusive practices.

This landscape review found:

- There is a distinct and emerging field of participatory and inclusive data stewardship, developing within and alongside other data stewardship models.

- The objectives and practices of those developing participatory and inclusive data stewardship are distinct from those of other data stewardship initiatives. They focus on collaborating with and empowering data subjects and those affected by collection, sharing and uses of data, often with a broader goal of supporting public benefit and a more equitable data ecosystem.

- Looking across sectors, participatory data stewardship practice is most mature in applications of data in the health sector, for example, voluntarily donated data initiatives or patient panels – a sector where there is already a high level of regulation and an established tradition of patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE).

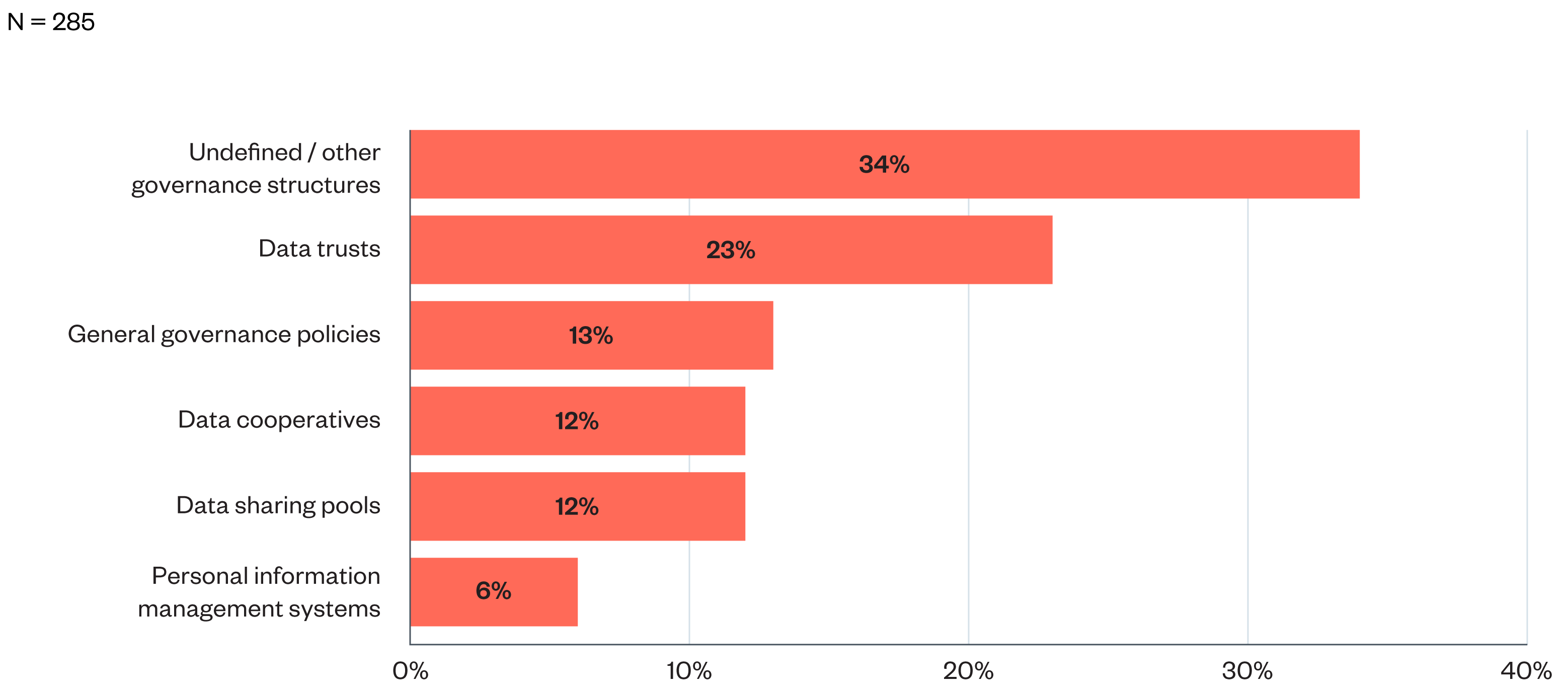

- Most examples of participatory and inclusive stewardship mechanisms identified were data trusts. This points to a preference for a mechanism with a clear legal underpinning, as well as the case for understanding, demonstrating and socialisation of alternative legal and participatory mechanisms that might meet different stewardship purposes.

- Participatory and inclusive data stewardship requires further time and investment, to test and potentially demonstrate its contribution to a healthy data ecosystem.

- Data stewardship itself does not have a fixed definition, and different understandings shape how it is used.For example, organisations that understand data stewardship as a responsibility to others (for example, data subjects, affected people or other beneficiaries) will have a different (and probably more participatory, and community- or public benefit-focused) approach than those that define their own standards for stewardship.

- Consistent practices and norms for participation and inclusion have not yet had time to develop: there are not yet mature models to provide sites for knowledge and expertise. Because proposed mechanisms are still largely theoretical or untested in practice over time, there are not yet transferable models or norms for the purposes, mechanisms, practices and outcomes of data stewardship.

- A holistic view of participatory and inclusive data stewardship mechanisms and practices is required, that extends beyond data governance to include all the practical (sociotechnical) infrastructure around the data, including organisational functions or community behaviours.

- There is not yet enough evaluative evidence to assess whether aspirations for participatory and inclusive data stewardship mechanisms are realistic, to demonstrate factors to support the sustainability of these initiatives, or their success – and whether they would deliver value if adopted and integrated systematically into data infrastructure, processes and decision-making.

- Legal and participatory mechanisms have different purposes and roles,and understanding and using both – and bridging between the two – has the potential to support building genuinely participatory and inclusive data stewardship.

- Legal mechanisms alone will not ensure that inclusive and participatory objectives (informing, consulting, involving, collaborating and empowering) are embedded in data stewardship initiatives. They play a critical role by underpinning these mechanisms, for example, mandating some aspects of informing and consulting for the public and private sectors, and enabling some aspects of empowering (like the right to data portability).

- Participatory mechanisms bring additional purposes and relational practices to data stewardship that support participation and inclusion, and enable inclusive and participatory objectives to be realised. They support rebalancing power towards data subjects, distributing power and value accrued from data to those affected by its use, and ensuring legitimacy and accountability to data subjects and affected people.

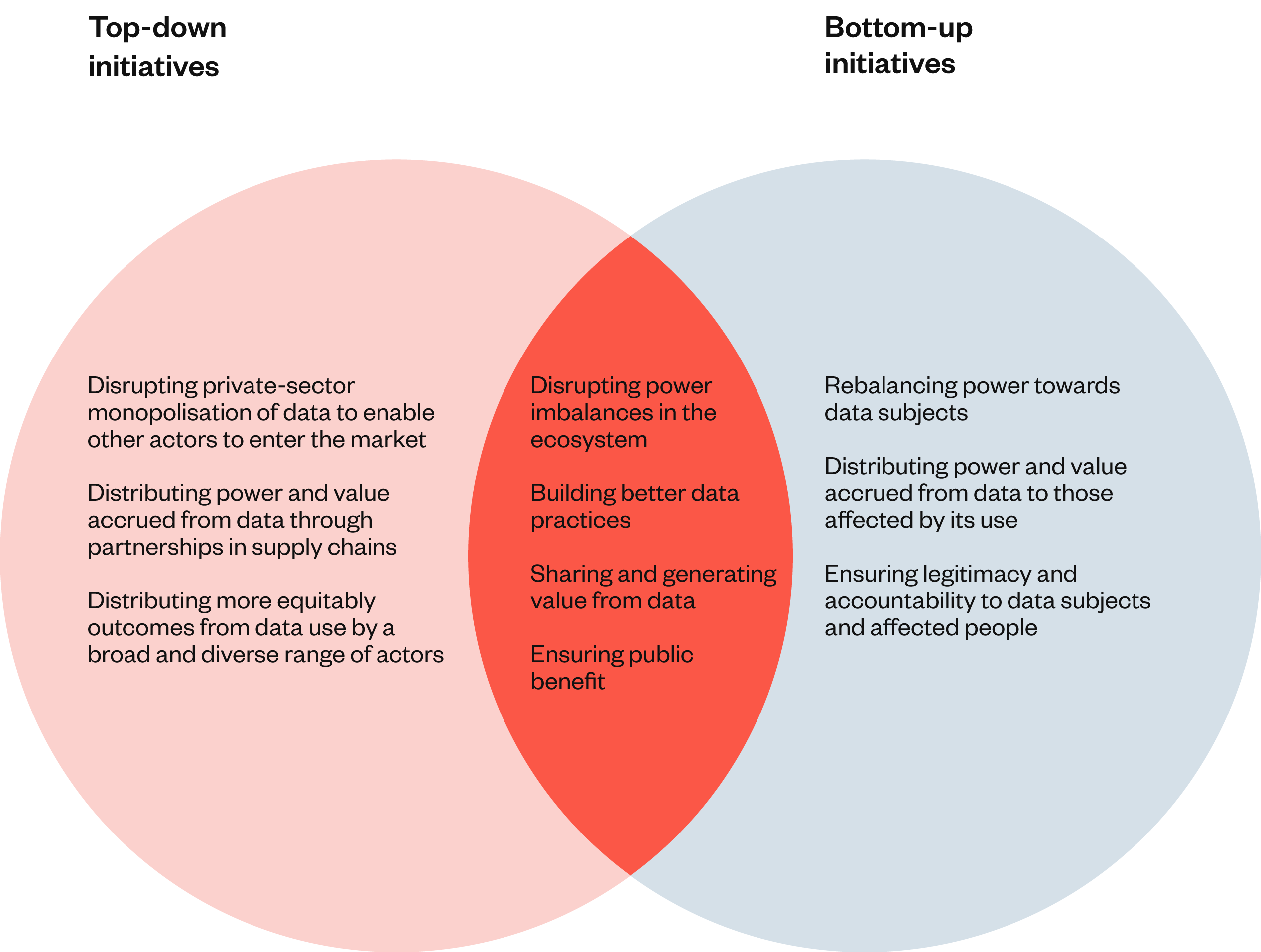

- Top-down and bottom-up data stewardship models have different purposes and practices. Top-down initiatives aim to build insights from data both for economic value and to maximise societal benefits. Bottom-up or community-led initiatives offer opportunities to challenge power asymmetries between decision-makers using data, and the people that the data represents and affects. These purposes use different methods, and lead to different outcomes. This means that just ‘doing’ participation isn’t sufficient – the way it is done matters.

- There is no single model for ‘good’ participatory and inclusive data stewardship, but a baseline would include: consideration and use of legal mechanisms to ensure rights and protections, as well as participatory mechanisms appropriate to the purpose and context, with responsibility and accountability to the requirements of data subjects, holders, beneficiaries and wider publics or affected people.

- Conversely ‘bad’ data stewardship (or ‘data stewardship washing’) would be characterised by: a lack of assumed responsibility or accountability in relation to the requirements of data subjects, holders, beneficiaries and wider publics or affected people. This would risk undermining the legitimacy and trustworthiness of the initiative, and broader public trust in data sharing.

- Conditions in the current data ecosystem have not proactively supported the initiation or development of a wide range of participatory and inclusive data stewardship mechanisms, and infrastructure and power so far remains centred in large corporations and platforms.

- The bar for participation in data stewardship is currently high for data subjects and individuals wishing to contribute. For participatory and inclusive data stewardship to become part of the data ecosystem, it must be easier for people who want to contribute meaningfully to understand the goals, administration and benefits of different models, set up or join data stewardship initiatives, or to perform processes like moving their data.

- There is a high bar for setting up and sustaining data stewardship initiatives. Interviewees with experience setting up and studying data stewardship initiatives reported consistent barriers of capacity to support participation and inclusion, and funding for sustainability.

- Legislation and regulation do not explicitly mandate participatory and inclusive mechanisms. Current legislation supports participatory and inclusive data stewardship through protection of rights and freedoms for data subjects. Within the data ecosystem, greater incentivisation of participatory and inclusive approaches may be needed to rebalance power in the ecosystem, or institutionalisation of participation and inclusion in governance practices.

- Within participatory and inclusive data stewardship, there are variations in theory and practice in relation to power, participation and inclusion that require further exploration:

- The relationship between participation and power is not linear (more participation does not necessarily equal more empowerment), for example in data-pooling mechanisms, some organisations rely on voluntarily donated data but afford individuals little control over how that data is used, while other models enable dynamic consent of voluntarily donated data and more formalised involvement in governance.

- High levels of participation do not always equate to high levels of inclusion. Questions around who is empowered to participate, and how, are complicated by structural and systemic inequalities. Inclusion is distinct and requires consideration not just that people are involved in decision-making, but – with attention to the context and specificity of the situation – which people are involved, and how.

- Mechanisms for inclusive data stewardship are less developed than participatory mechanisms. This points to the need for more investment into the theory and practice of inclusive data stewardship mechanisms. For example, data stewards acting as trusted intermediaries could have a critical role in the data ecosystem, bridging the gap between participation and inclusion.

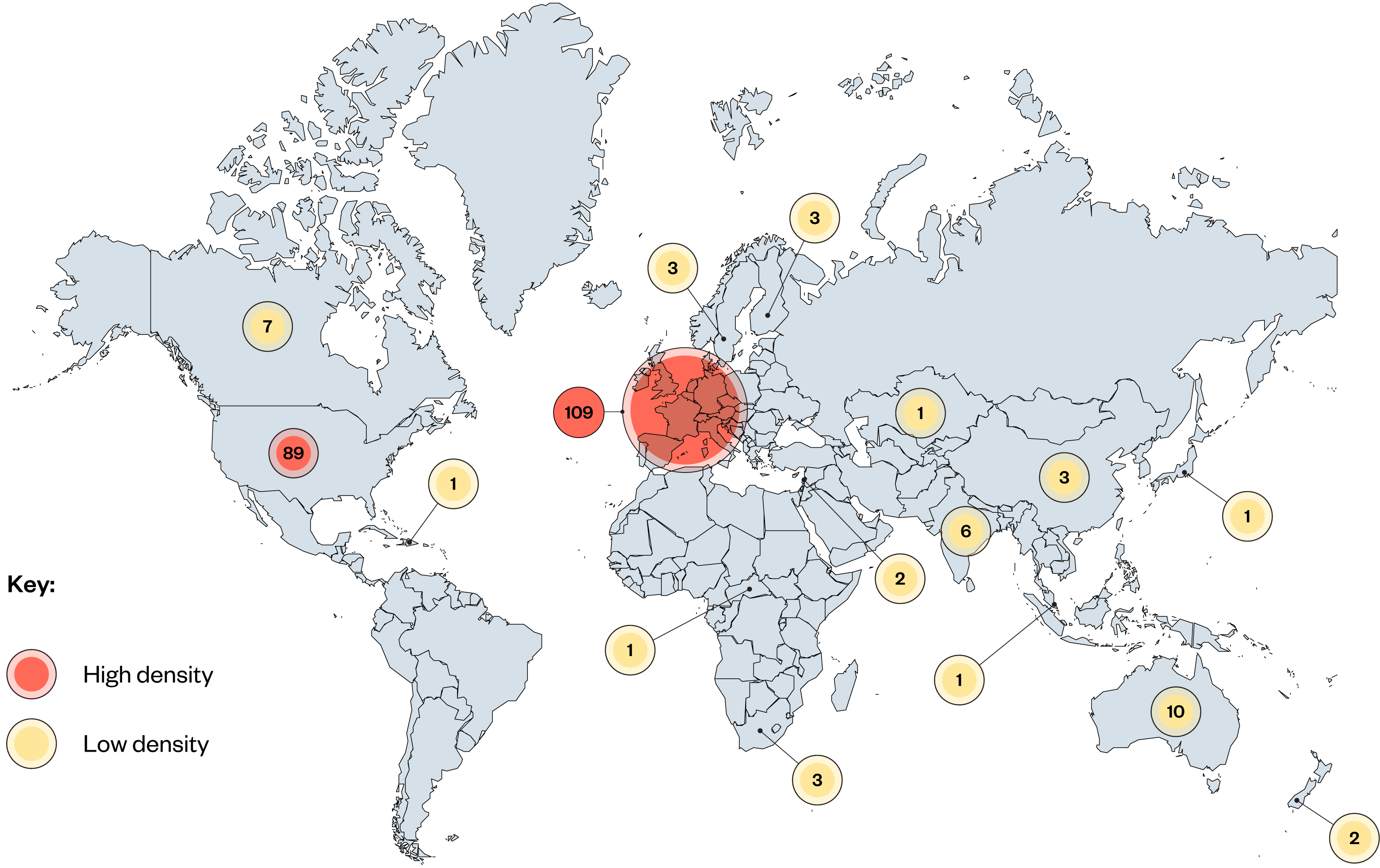

- White-majority and English-speaking-centred literature and organisations are overrepresented within the literature we identified. This is partly due to methodological limitations , but points to a need to explore, understand and learn across existing approaches in other domains and jurisdictions.

- There is an indication that governance frameworks in white-majority countries that afford more power to individuals do not neatly translate across cultures and geographical areas, and particularly into countries where the majority of people are black, Asian, brown, dual-heritage or Indigenous to the global south. For example, structural inequalities and power asymmetries, such as those resulting from the legacies of colonialism, complicate how data initiatives translate.

- Some discourse assumes a comprehensive adoption of western definitions of data ‘ownership’ as property, which overlooks other cultural approaches to ownership, belonging and stewardship as knowledge relating to different peoples. For example, governance innovations in relation to Indigenous data sovereignty model different approaches to inclusion and cultural knowledge around data and data ownership, where perspectives of value go beyond monetary measures.

While this review does not provide specific recommendations to policymakers and practitioners working in this field, we hope this research will provide a foundation for future research and the development of practical mechanisms to further test the utility and efficacy of participatory and inclusive data stewardship in supporting a healthy data ecosystem that fosters societal benefit.

How to read this report

To understand and explore participatory and inclusive data stewardship and its potential to help shape a healthy data ecosystem, see:

- To understand what data stewardship is and the role it can play (Introduction: Definitions; What is data stewardship?)

- For an introduction to how participatory approaches can support emerging norms and practices that build on legal underpinnings to create more participatory and inclusive outcomes (Introduction: What is the role of participatory and inclusive practices?)

- To understand the current state of the landscape (Landscape review)

- To explore perspectives of people working in the landscape (Interviews: 1. Definitions and terms used in this field vary; 3. Participation takes many shapes and forms in the data lifecycle; 4. Mechanisms for inclusion are less developed than mechanisms for participation)

- To read a summary of our insights (Conclusion: What can we say about participatory and inclusive data stewardship?)

To understand different purposes and dynamics in the current data ecosystem, and how they shape approaches to participatory and inclusive data stewardship, see:

- A summary of structural or systemic issues and barriers (Introduction: What are the current conditions in the landscape?; Challenges for participatory and inclusive data stewardship)

- An exploration of different, complementary and competing incentives and purposes (Introduction: Different purposes for data stewardship)

- Examples of different purposes (Frameworks for participatory and inclusive data stewardship: Purposes)

- Insights from the landscape review (e.g. Landscape review: The relationship between participation and power is less linear than previously conceptualised)

- Insights from interviews (Interviews: 2. Purpose matters to comfort with different uses)

To understand how intersections of legal and participatory mechanisms can contribute to building a healthy data ecosystem, see:

- How legal rights and protections underpin existing participatory data stewardship mechanisms (Introduction: What is the role of legislation?: Analysis of legal and participatory mechanisms: Existing legal underpinnings for data stewardship)

- How different data governance mechanisms are more or less supportive of participation and inclusion (Emerging mechanisms for data stewardship: Table 1: participatory mechanisms; Table 2: Participation-supportive mechanisms; Table 3: Non-participatory mechanisms)

- An analysis of existing legislation in the UK and EU, see Existing legal underpinnings for data stewardship and Appendix: Legal underpinnings (EU)

- How existing mechanisms and frameworks build on legal underpinnings to support participatory and inclusive outcomes (Table 4: Mapping legal and participatory mechanisms to objectives for data stewardship; Frameworks for participatory and inclusive data stewardship: Purposes, Operational norms and Inclusion)

To understand objectives and activities of bottom-up practices that support participation and inclusion in data stewardship, see:

- Examples of participatory and inclusive data stewardship projects (Introduction: Data stewardship in practice)

- Analysis of academic, grey literature and practical examples of approaches that seek to collaborate with and empower data subjects and beneficiaries (Landscape review)

- Perspectives of academics and civil-society organisations developing and advocating for participatory and inclusive practices (Interviews)

- Legal analysis of how rights and protections underpin existing mechanisms, and where participatory practices build additional structures for inclusion and empowerment outcomes (Table 4: Mapping legal and participatory mechanisms to objectives for data stewardship; Frameworks for participatory and inclusive data stewardship: Purposes, Operational norms and Inclusion)

To explore objectives of emerging top-down, large-scale data sharing initiatives, see:

- For a description of current ecosystem dynamics and potential tensions. (Introduction: What are the current conditions in the landscape, Challenges for participatory and inclusive data stewardship and Different purposes for data stewardship)

Next steps:

- To understand our overall insights (Executive Summary: Insights)

- To see recommendations for next steps for research and practice (Conclusion: Observations about the landscape)

Introduction

This landscape review aims to present a snapshot of current theory and practice in participatory and inclusive data stewardship, and to identify and analyse trends and developments. It takes a multidisciplinary sweep through relevant literature and thinking to explore how early examples of theory and practice intersect with motivations for data stewardship that supports individual and public benefit.

The review focuses primarily on the mechanisms and purposes of data stewardship, and who – or whose interests – participatory and inclusive data stewardship could or should serve. This includes how it is related to already available mechanisms and approaches, and how those might be developed or disrupted by current theory and practice.

While acknowledging the emerging nature of the field, it explores relationships between underlying legal assumptions (for example, of lawful, proportionate and necessary processing of identifiable data to ensure groups, rights and interests are represented and protected), and of participatory practices (for example, that if some groups of society are continually underrepresented in data stewardship practices, then power asymmetries in data will persist).

As well as participation, it has a specific focus on inclusion, understanding that these concepts need to be considered in relation to each other, rather than as discrete practices, because participation without inclusion is insufficient to ensure equitable outcomes.

Approach to the research

Considering data stewardship comprehensively (as a set of concepts, practices, expertise and mechanisms that are grounded in social realities) is complex. Our methodological approach has responded to this challenge, and has aimed to simultaneously envision, review and examine the developing ecosystem of participatory and inclusive data stewardship. At the same time, we have iterated and refined our methods, leading to different approaches that reflect and probe into multiple understandings of participatory and inclusive data stewardship.

Early research activities showed mapping current data stewardship development requires exploration of practical implementations of legal, structural and systemic preconditions that determine how data is valued, donated, collected, managed, controlled, accessed, owned and shared. And that these concerns intersect with societal questions of belonging, consent, ownership, responsibility, citizenship, safety, privacy, transparency, individual and civic rights, individual and collective benefits, power and agency, equity and trust.

A question that informed our research design at an early stage was how and where to locate the expertise around participatory and inclusive data stewardship. The evidence shows that such expertise is found in practice-based community and civil society organisations and academia, crosses institutional and social domains, and is – by its nature – grassroots.

Through database keyword searches we identified where those activities were located in theory and practice, and which individuals and organisations were dominant in the literature. From there, we saw differences in the organisations we had identified in the keyword searches and those coming out as examples in the analysis. We used this knowledge to select interviewees who represented different aspects of this expert and informed landscape.

One early outcome was an understanding of the need to locate evidence about current practices in an analysis of preconditions or underlying factors in the wider data and AI ecosystem, and this informed the work on legal and participatory mechanisms. This led us to explore those differences and locate potential tensions between the two dominant areas of activity we identified – which we call ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’. See also Methodology.

What are the current conditions in the landscape?

Data stewardship – the responsible use, collection and management of data in a participatory and rights-preserving way – is a young and developing field, in which different mechanisms are being used and trialled in a variety of models and pilots, for different purposes. There are many small-scale examples originating in academia, civil society and communities that demonstrate good practice and experimentation across a range of participatory mechanisms and practices.

Data stewardship in practice

This review does not go into detail about specific data-stewardship initiatives, but we acknowledge the importance of that evidence and of the developments taking place in participatory practices.[10] To provide a sense of the breadth of that work, examples of data stewardship mechanisms are described here, selected by interviewees and through our research, as examples that illustrate significant trends in the wider landscape:

The Native BioData Consortium (USA)[11] describes itself as the first nonprofit research institute led by Indigenous scientists and tribal members in the USA. It stores biological samples and data from tribal members local to their community; builds tribal capacity in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) research; and aims to build more robust health datasets to investigate health outcomes that benefit Indigenous people.

‘This is an Indigenous-led initiative that’s in part a biobank but also a data repository. They’ve been acting as a third party where they will hold data until a tribal nation works out what it’s going to do with it. There are examples where they have held data temporarily and then it has been deposited with the tribal nation.’

– Maui Hudson, Director, Te Kotahi Research Institute

Abalobi (South Africa)[12] is a South African-based civil society organisation with international reach that describes itself as a hybrid social enterprise with a vision to develop ‘thriving, equitable, resilient and sustainable’ small-scale fishing communities globally. It offers a suite of fisher-driven technologies to support data collection and application across the fishing supply chain, from electronic catch documentation and traceability through to area-specific marketplace information.

‘A good example of data stewardship that works well is Abalobi in South Africa. They built an app for small fishing communities in South Africa on the coast to track the whole process from the time the fish was caught all the way to when it’s sold. It’s surfaced the role of women in this whole cycle. Because the labour of women – usually as either sisters or wives or daughters – was just assumed, and [the app] surfaced their labour and allowed them to get remuneration for it. This was not data that the government was going to be able to collect at all easily, but it’s a big data gap that they [Abalobi and the fishers] were able to fill.’

– Vinay Narayan, Senior Manager, Aapti Institute

The Data Assembly (New York, USA)[13] is an initiative from The GovLab to gather diverse and actionable input on data re-use for crisis response in the USA. The initiative began in New York City in summer 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It consisted of remote deliberations with three publics: data holders and policymakers; representatives of civic rights and advocacy organisations; and New York residents and visitors.

‘Something we did here in New York City during COVID-19 was to work on accessing data reuse to inform pandemic response and preparedness. The Data Assembly was the first-ever citizens’ assembly around the reuse of data, to inform the City government on what New Yorkers – broadly defined as residents and visitors to New York – felt was appropriate and under what conditions data could be reused. The key element here was who was holding the assemblies? We had public libraries hosting, which was an important design feature.’

– Stefaan Verhulst, Co-Founder, The GovLab (New York) and The Data Tank (Brussels)

Saidot (the Netherlands and Finland)[14] produces open AI and algorithmic registers that support informing and empowering people by enabling an ‘armchair audit’ of AI systems in Helsinki and Amsterdam. In our 2021 Participatory data stewardship report,[15] we observed that Helsinki and Amsterdam were among the first cities to announce open AI and algorithm registers. These were founded on the premise that the use of AI in public services should adhere to the same principles of transparency, security and openness as other city activities, such as public bodies’ approaches to procurement.

These registers are openly available, and accessing the register reveals information about the systems that are reported on, the information that is provided, and the specific applications and contexts in which algorithmic systems and AI are being used. Saidot conducted research and interviews with clients and stakeholders to develop a model that serves the wider public, meaning it is accessible not only to tech experts but also to those who know less about technology, or are less interested in it. Saidot has demonstrated longevity as a model: as of 2024 the registers remain in use in Amsterdam and Helsinki.

Our Future Health (UK)[16] is a collaboration between public- and private-sector organisations and charities that has developed a trusted research environment (TRE) for health data. It aims to be the UK’s largest-ever health research programme, supporting wellbeing and longevity through better prevention, detection and treatment of disease. Our Future Health assures participants that their data will only be used in the context of health and disease, and that they can withdraw consent at any time. The programme has involved members of the public through focus groups, interviews and a public advisory board.

Safetipin (India)[17] describes itself as a social impact organisation working towards building responsive, inclusive, safe and equitable urban systems with a particular focus on women’s safety. It collaborates with government and non-government stakeholders to use big data to improve infrastructure and services in cities. Data is collected via a mobile phone app in multiple ways. Some of the data is crowdsourced, for example, through a mobile app on a car windshield taking photos or user feedback on safe/unsafe areas. Others are collected on a project basis by, for example, trained Safetipin associates collecting data about accessibility of bus stops.

‘Safetipin is an organisation that maps the safety of streets, and they’ve worked with local school children – particularly girls – who don’t have access to mobile phones, to map street lights and any particular things that make them feel nervous, or things that feel dangerous on their streets on their walk home. So they’ve done ethnographic walks with participants, noting where they feel nervous.’

– Joe Massey, Senior Researcher, Open Data Institute

Aya, Cohere for AI (international)[18] is a global open science project to create new multilingual models and datasets that expand the number of languages covered by AI, and the quality of the language data. It is one of the largest open science machine learning projects to date, involving over 3,000 independent researchers across 119 countries and 101 languages. The open-source dataset is generated through working with fluent speakers of languages from around the world to collect human-annotated instruction data in relation to specific languages for AI research.

‘Data contribution is not necessarily very participatory, but it is an activity that enables a lot of people to get involved. Cohere for AI’s Aya initiative has built out multilingual datasets that otherwise would not have existed. Many times these organisations have joined primarily for another purpose, whether that’s digital preservation of a language, or wanting the dataset for their own purposes to build language models or technology that’s purpose-built for their languages. It’s been an interesting opportunity for different groups to engage with specific communities to help achieve mutual goals.’

– Jennifer Ding, Senior Researcher, The Alan Turing Institute

The Data Trusts Initiative (UK)[19] supports pilot projects that bring together researchers and social entrepreneurs to explore how to move models for data trusts from theory to practice. Its aim is to empower individuals and communities, while supporting data use for social benefit. Current pilots include the Brixham Data Trust, which explores facilitation of environmental stewardship, health, wellbeing and net-zero ambitions in the context of a small fishing town. The Born in Scotland Data Trust seeks to tackle the economic and healthcare inequalities affecting communities in Scotland by building an infrastructure for trustworthy data stewardship around a pilot birth cohort study. The General Practice Data Trust is investigating how data trusts could help steward healthcare data in the UK. In particular it focuses on the million people who have opted out of the NHS General Practice Data for Planning and Research (GPDPR) programme due to concerns about how their data will be managed and used, and aims to give them an alternative opportunity to participate in life-saving research.

Driver’s Seat Cooperative (USA)[20] launched in 2019, to empower gig workers – particularly in the transport sector, for example cab and delivery drivers – with tools to advocate for better pay and to combat the arbitrary use of algorithmic management systems that put them at an unfair disadvantage and undermined their rights. The Driver’s Seat app allowed workers to share and analyse insights from their data, providing transparency about payment, distance and time, to counter discriminatory or unfair remuneration practices. The objective was to build a cooperatively owned and directed business, creating worker-initiated data not only to empower workers but also to inform workplace and transportation policymaking.

The Driver’s Seat app had 20,000 downloads and successfully supported gig workers to represent their rights and campaign for more equitable working conditions, particularly in the San Francisco area. Despite this, it was not able to sustain a profitable business model. However, the cooperative and democratic decision-making model persisted, and members were invited to vote on the closing plans.[21]

In 2024 the app and tools transitioned to become part of the Workers’ Algorithm Observatory, a crowdsourced auditing collaboration at Princeton University.[22]

‘In 2021 we did a landscape mapping to identify a bunch of data stewardship initiatives. Last year they went back to see where those organisations are, and I think the biggest thing is that most of these organisations don’t scale too well. Funding is a big challenge – most of them rely on philanthropic fundraising or grants, because there isn’t much monetary value in these models. A cooperative where you charge your members a fee might work better… A lot of models fail to move past the pilot stage, and even when they do, funding continues to remain a concern. Driver’s Seat is a prime example: they’ve been around since 2019 but had to close shop last year due to a lack of funds.’

– Vinay Narayan, Senior Manager, Aapti Institute

Challenges for participatory and inclusive data stewardship

All these activities are taking place in a landscape characterised by imbalances of power, concerns about the safety of new technologies, national and global regulation lagging behind the development and deployment of new products and services, and low trust in data sharing.[23], [24] In addition, there are concentrations of data in silos and market dominance in a small number of multinational companies, high-profile data-sharing errors and opaque private–public partnerships that continue to undermine public trust in responsible data governance.[25]

While we do not suggest that participatory and inclusive data stewardship alone can remove the inequities in the current data economy[26] – that requires a fundamental restructuring of the institutions and distributions of economic power[27] – we do propose that it can make a contribution towards disrupting private-sector monopolisation, rebalancing power towards data subjects and those affected by data sharing and use, and supporting collective or public-interest outcomes.

In relation to data, it is understood that ‘in the current data ecosystem, the most valuable data is generated about individuals without their knowledge or control’.[28] This is because private companies hold disproportionate power in the data ecosystem, often assuming the role of data intermediary through creating and harvesting data as part of their business models. This is particularly true in relation to the African continent, where there are high aspirations for data sharing to develop research and policy in relation to ‘deficit narratives’ that highlight only systemic poverty or inequality. These conversations are commonly pursued by non-African stakeholders, while datasets are extracted from African communities.[29]

Making space for participatory and inclusive data stewardship would mean ‘disintermediating’ the existing system. This would involve disrupting the ways that companies, including monopolistic platforms, routinely insert themselves into technical, social and economic interactions to create or extract data and control access. Often they do this without creating value for data subjects,[30] or distributing value through different actors in a supply chain – including, for example, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).[31]

This power hold is reflected in companies’ internal practices, and the limited extent to which these companies engage with or attend to participatory mechanisms.[32] There is evidence that this tendency towards a technocratic approach is reflected in the public sector, where ‘data stewards’ take responsibility for communicating findings to diverse audiences, such as other public servants or communities, but assume that people with non-technical backgrounds may struggle to understand complexities.[33]

The lack of established models for participation and inclusion presents another challenge. For those wishing to set up participatory data stewardship initiatives, it is necessary to understand and be able to mobilise a range of knowledge and skills. Existing frameworks do not yet capture communicable and transferable norms. An exception is the Aapti Institute playbook, which is presented through challenges experienced on the ground, and potential strategies or solutions in relation to ‘sector-specific nuances, requirements and realities’.[34]

There are also longer-term examples from the health sector, where patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) practices do have established norms.[35] Recent research in the health sector provides learnings for new participatory mechanisms like data trusts; for example, the process of involving people in the governance of large-scale biobanks. This highlights the need to attend to who is involved and their interests, who speaks on behalf of whom, distinctions between – and the existence of – multiple publics.[36]

However, a study of public attitudes, hopes and concerns in relation to the use and sharing of NHS data found that – despite these more established norms – the public want more transparency, accountability, public participation and fairer distribution of benefits.[37] Dynamic (rather than ‘informed’) consent, which enables data subjects to maintain control over time in relation to how their data is (re)used, for which purposes and by which actors, is well researched in relation to biobanks but not yet an embedded practice in other contexts.[38]

The rise in interest in generative AI technologies brings novel challenges for participatory data stewardship, including the increasing prominence of debate around AI, algorithmic and machine-learning technologies’ safety and governance. While this focus has overshadowed recent public discourse around data, it also highlights the essential role of data and datasets in the development and deployment of AI technologies, in model training and processes like prediction.

The pervasiveness of AI and the distributed nature of the supply chain, which can involve multiple companies as developers and deployers of AI, or holders and users of data, requires new models for meaningful stewardship in practice at different decision-making points.[39], [40] There is optimism that participation can overcome the perception that AI – even as it develops into increasingly human-interaction spaces – is disconnected from social governance.[41] And that participatory practices can turn the current appropriation of scale by multinational corporations into infrastructure and resources that distribute power and enable localised communities to represent their own interests.[42]

In the absence of participation-focused regulation, AI companies are making their own decisions in relation to appropriate protections for creators and holders of data,[43] and – with some notable exceptions, such as those building open-source datasets – show little evident concern for empowerment through meaningful participation.[44] Many AI companies have been training their models on publicly available (if not always openly licensed) data, and are now looking to increase the performance of their models and market privilege by buying access to private datasets.[45]

One example of a resource that is at risk of being undermined is the New Zealand-based Te Hiko database and transcription software, developed by and for the Indigenous community to preserve and share intergenerational recordings and knowledge about the te reo Māori language. Managed as a pooled resource, the collective has protected its irreplaceable dataset through a hosting and licensing arrangement, but recognises its vulnerability to AI model training and is calling for revisions to intellectual rights and copyright law.[46]

More recently, there has been a focus on building large-scale, public data infrastructure through a burgeoning of public interest AI discussions.[47] In practice, this means that public institutions, service-providers and private companies – which have started to amass considerable power and/or responsibility through holding or using data – wish to build insights from data both for economic value and to maximise societal benefits.

With this comes a responsibility to balance the potential of economic and societal benefits through:

- Mechanisms that will enable those in stewarding roles to ensure protections of fundamental rights and freedoms encoded in law – such as privacy, data protection and safety.

- Mechanisms that will enable inclusive consideration of people whose data is included in these large datasets (albeit anonymously and beyond the reach of data protection legislation), and who may be affected by decisions based on large-scale analysis and insights.

In these large-scale data-sharing initiatives that steward smart or non-personal data, there is a narrow definition of stewardship emerging that removes the sense of (fiduciary) responsibility. Instead they use language of working towards an abstract notion of good or public benefit that is not legitimised by a relationship with the needs or interests of data subjects or beneficiaries. In addition, these initiatives tend to use mechanisms at the low-participation end of the spectrum, in accordance with legal requirements, but not using participatory mechanisms. The result of this is a risk of potentially unparticipatory and uninclusive data stewardship emerging that could be called ‘data stewardship washing’.

Definitions

Data stewardship is itself a contested term, even without the layering of participation and inclusivity. In addition, legal and normative definitions are used to refer to different actors in the data stewardship supply and value chains. This review uses the following terms:

Data: refers to information about people, activities and the physical world. Data cannot be neutral: when we consider data, we must also consider the sociotechnical structures around its collection and use. An important distinction in relation to how it is stewarded is whether it is subject to specific legal requirements and processing as personal data (‘related to an identified or identifiable person’ as defined by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)) or is subject to less scrutiny as non-personal data (such as anonymised data, sensor data of traffic flows or Internet of Things).

Data intermediary: any mechanism or service that seeks to manage and intermediate relationships responsibly between individual data subjects, data holders and data users (see definitions below). Note: while many corporate platforms are currently technically de facto ‘data intermediaries’, our definition of data intermediary assumes a purpose beyond direct commercial value from data sharing, which benefits data subjects, holders, affected people and wider society, as well as those who make use of the data.

Data steward: the independent person, organisation or institution that creates a trusted environment which supports decisions about access and sharing of data subjects’ and data holders’ data. This will include supporting them to exercise their rights, make informed choices, consult and exchange views on data processing purposes, and negotiate terms and conditions for data processing on their behalf. Incentives for data stewards vary according to the purpose, terms and objectives set.

Data subject: the individual holding rights over their personal data, for example the right to access, erasure, rectification, portability.

Data holder: the person, organisation or institution who has obtained the right to grant access and share data to which the data subject(s) has / have rights.

Data management service provider: the organisation providing the service through which an individual’s decisions about their data are operationalised. The service provider makes decisions over the scope and design of the technical architecture of decision flows, and is generally not involved directly in the individual’s decision-making process. These organisations do not take an active stewardship role but can influence positively or negatively through the interface design (for example, the platform could nudge individuals to consent to sharing data for certain causes that might involve public benefit).

Data user: the person, organisation or institution receiving access to data and using data to which the data subject has rights.

Affected people: anyone who might be affected positively or negatively by data-processing practices.

‘Bottom-up’ data stewardship: any mechanism where decision-making power is held by the data subjects, and entry and interaction into relationships within the existing data ecosystem requires legal or administrative arrangements to empower data subjects to take a more active role in stewarding data about themselves, by granting access under specific conditions or protecting sensitive data.[48] These stewardship arrangements would 1) codify consultation and participation in the foundational governance documentation and 2) enact the consultative and participatory mechanisms set out in the governance framework.

Top-down data stewardship: any mechanism where decision-making power is located with the data holder (such as platforms, Government, local government or health and welfare infrastructure), and equitable activity in the existing data ecosystem requires mechanisms to facilitate the participation of data subjects and / or affected people (as part of, or in addition to, a legal or administrative structure). These organisations might be combining or linking data from multiple sources, or acting as a gatekeeper for data held by other organisations.[49] Other descriptors used are private or civic data trusts.[50]

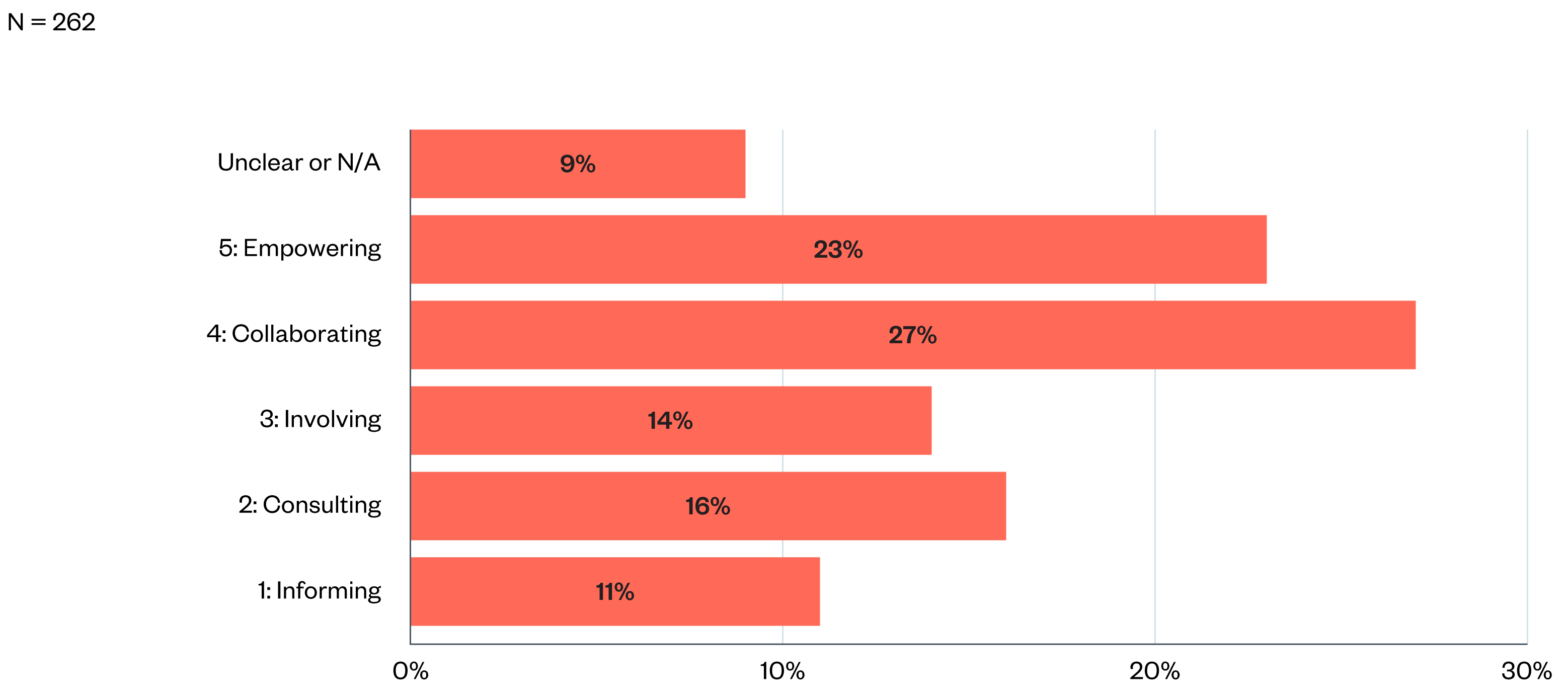

Participation: the involvement of people in meaningfully influencing and shaping or effectively making decisions that affect their own lives and wider societal outcomes. Meaningful participation in data stewardship will reflect the motivations and aspirations of those participating, so there is no single model – in some situations, people will want others to take responsibility for, and carry out, work required to ensure their views are heard and taken into account, and in others people will want to play an active role. Therefore, it is necessary to frame participation in terms of a range of outcomes: informing, consulting, involving, collaborating or empowering people.

Inclusion: the ability of diverse groups of people and individuals to meaningfully participate in the stewardship of their data, with a secondary focus on how this participation brings individual or wider community or societal impacts. Inclusion is relevant to both the process and outcomes of data stewardship: excluding individuals and groups of people from the design of mechanisms prevents their participation in decision-making, and excluding them from lawful, necessary and proportionate data collection prevents their representation in initiatives built on those datasets – undermining public benefit. Inclusion requires a specific focus on equity and rebalancing power.

Note: our report Participatory data stewardship used the collective term ‘beneficiaries’ to refer to a number of different actors who might be affected by the use of data and might have the potential to benefit from a participatory data stewardship approach. The intention was to move beyond a ‘compliance-based approach’ to one underpinned by social licence. Our current thinking is that distinguishing data subjects and affected people in the context of specific datasets enables a clearer understanding of relevant differential legal, technical and organisational factors operating in the current data ecosystem in relation to data stewardship. Legal protections are grounded in the identification of individual rights holders and affected people in specific contexts, and beneficiaries is used to indicate those – including individual rights holders and affected people – who stand to benefit in any way from specific, normative, participatory mechanisms.

What is data stewardship?

Data stewardship is a relatively new concept: it has been a recognised mechanism for the responsible and trustworthy management of data among national and local policymakers, civil society and communities for less than a decade. How stewardship is defined in relation to data-sharing initiatives matters, because it determines how responsibility, legitimacy and accountability are conceptualised and operationalised.

Stewardship encompasses practices that are rooted in legal protections, such as data protection law that ensures a blanket level of protection for data processing practices (the section below also discusses participatory elements in data protection law), or trust law that can serve as basis for new data governance models such as ‘data trusts’ with embedded fiduciary obligations. Stewardship also encompasses social and organisational norms that extend beyond the management of data into ways of working and standards of practice.

In the UK, the push towards seeing data intermediaries (for example, data trusts) as a realistic mechanism to facilitate data sharing for economic growth, encourage competition and develop a trusted and safe way to share data, dates to around 2016. Since then, global initiatives have developed that bring prospects of multiple new institutions and mechanisms for involving and empowering people through data stewardship, shifting the focus from who owns the data to who takes responsibility for its use, and on whose behalf.

As this review demonstrates, there continues to be an established and live discourse around ‘data stewardship’ theory and practice. This encompasses multiple definitions and understandings of key terms – including data stewardship itself: data stewardship can be understood as both an institutional approach, and also a set of functions and competencies. The Ada Lovelace Institute’s (Ada’s) working definition of data stewardship has been ‘the responsible use, collection and management of data in a participatory and rights-preserving way.’[51]

This implies that data stewardship should be understood as embodying a principle of responsibility – not just to the interests of one’s own self or organisation, but to the interests of others. This relationship can be ‘fiduciary’, denoting a specific legal responsibility with – for example, in the case of data trusts – obligations to ensure trustees act in the best interests of those creating the trust.

The relationship between stewardship and governance is similarly contested: some see stewardship as a subset of data governance, some focus on stewardship’s focus on a societal goal as opposed to ‘governance’s focus on processes for making decisions and exercising power,[52] while others see stewardship encompassing data governance as ‘the process by which responsibilities of stewardship are conceptualized and carried out’.[53]

Using the term ‘data stewardship’ can indicate an approach to data management that builds on governance – the structural conditions that enable data to be used in trustworthy and inclusive ways – towards an approach that broadens compliance into consideration of rights, responsibilities, common good and mutual or public benefit.[54]

This conception of stewardship has its roots in the work of economist Elinor Ostrom, who used stewardship to identify harmful and beneficial practices in the governance of natural resources.[55] Data is not a traditional resource – and there are some properties of data, such as its ability to be shared and re-used, that make it distinct from natural resources. However, stewardship has become established as a useful positioning concept to enable consideration of how data is collected, used and governed in systems of power inequalities, for what purposes and in whose interests.

These definitions are culturally conditioned, and there remain substantial differences between knowledge and conceptions of Global North and Global South countries, policymakers, companies and researchers – as well as a tendency to present dominant (Global North) narratives as implicit norms. Continuing ‘data colonialism’ freights many assumptions of unjust historic actions, perpetuating the deficit model by overlooking plural, community-centred data practices, values and traditions, as well as scientific and cultural developments within the 54 African nations.[56]

Accepting the need for a ‘decolonial approach to data’ that broadens the range of possible models and solutions beyond western-centric assumptions,[57] there are still inconsistencies in the definition, responsibilities, goals and relationships implied by data stewardship. Some see stewardship embodied in distinct organisations and processes, and others see it as an active, negotiated and relational dynamic between interested parties. Data stewardship can therefore be both an institution and a set of practices.[58]

Data can be seen to have different relationships to societal norms of ownership and property, and many initiatives seek to maximise the collective, societal value of data as a ‘commons’, rather than its individual, property-based or monetisable value. Notions of data ownership, which stem from equating data governance straightforwardly with property rights[59] rather than human rights law,[60] differ depending on relationships to empowerment and cultural geography. Some arguments recommend strengthening individual control, while others recommend increasing collective control and increasing the prominence of public value or benefit.[61]

The mechanisms for stewardship are also unsettled and evolving, despite specific work to review and typologise intermediaries that aims to add to the knowledge base and identify emerging types, to contribute to common terminologies.[62] The different views of data stewardship in practice reflect the positionality of interested organisations, their place in the context of current debates and the purposes they propose. The UK Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (now the Responsible Technology Adoption Unit) defined data intermediaries in 2021 as ‘a broad term that covers a range of different activities and governance models for organisations that facilitate greater access to or sharing of data’.[63]

In 2021 the GovLab called for a reimagination of data stewardship to encompass ‘functions and competencies to enable access to and re-use of data for public benefit in a systematic, sustainable, and responsible way.’[64] In 2022 the Open Data Institute recognised the need to disambiguate data institutions and intermediaries, recognising the similarities (both terms recognise organisations that empower individuals as well as organisation-to-organisation approaches; and both are mechanism-agnostic). Intermediaries may facilitate data-sharing, and institutions take on a broader set of functions, including stewardship and the responsibility to steward data on behalf of a particular sector or community.[65]

In considering setting up a central government data ethics body, the Royal Society focused on the responsibility embodied in a stewardship relationship, describing it as a body mandated to ensure responsible use of data.[66] In the Mozilla Foundation’s introduction to concepts, it took a more power-differential view, describing stewardship as the act of empowering agents in relation to their own data.[67] The Open Data Institute described it as embodying a ‘fiduciary relationship’ of trust between data stewards and data beneficiaries[68] – it has now updated this definition to ‘the collection, maintenance and sharing of data’.[69] And the Aapti Institute described a process designed to empower individuals and communities while protecting rights: ‘a paradigm which explores how the societal value of data can be unlocked while considering what it takes to empower individuals/communities to better negotiate on their data rights’.[70]

Definitions of data stewardship centre on the positionality of the power-holder, with an assumption towards governance models that do not involve state or market actors. Early conceptualisations involved a tacit assumption that the trusted relationship implies a ‘fiduciary’ duty in which the interests of individuals or groups of people are protected and cared for by a responsible person or body: ‘The concept of a data steward is intended to convey a fiduciary (or trust) level of responsibility toward the data.’[71] This model carries assumptions about who might assume that trusted role – usually an organisation or professional operating under a legal responsibility.[72]

Although there is no fixed definition of ‘data stewardship’, it is intimately tied to existing legal protections, such as privacy, security and human rights. However, these legal bases for governance have been supplemented by normative activities, behaviours, approaches or frameworks. These are frequently found in academic, civil society and community models, and are specifically designed to foster and enable the creation of participatory and inclusive data stewardship models and practices, which increase agency and support empowerment of people.

In practice, data stewardship cannot be structured effectively through only legal or participatory means: it is the combination of legal and participatory mechanisms and practices that produce the normative rules and behaviours that structure specific data stewardship mechanisms. These norms instantiate the equity and inclusiveness of a particular stewardship mechanism and the agency it provides, while also providing the relational aspect of reliable governance mechanisms that protect the rights and interests of those who currently hold less power in the data economy (for example, data subjects and civil society organisations who represent their interests, small companies and local public authorities).

Emerging mechanisms for participatory and inclusive data stewardship

To understand the current ecosystem of participatory and inclusive data stewardship, it is necessary to understand their legal governance mechanisms, relative to power-holding and sharing, and how these support more-or-less participatory processes and outcomes (whether participants are informed, consulted, involved, collaborated with or empowered).

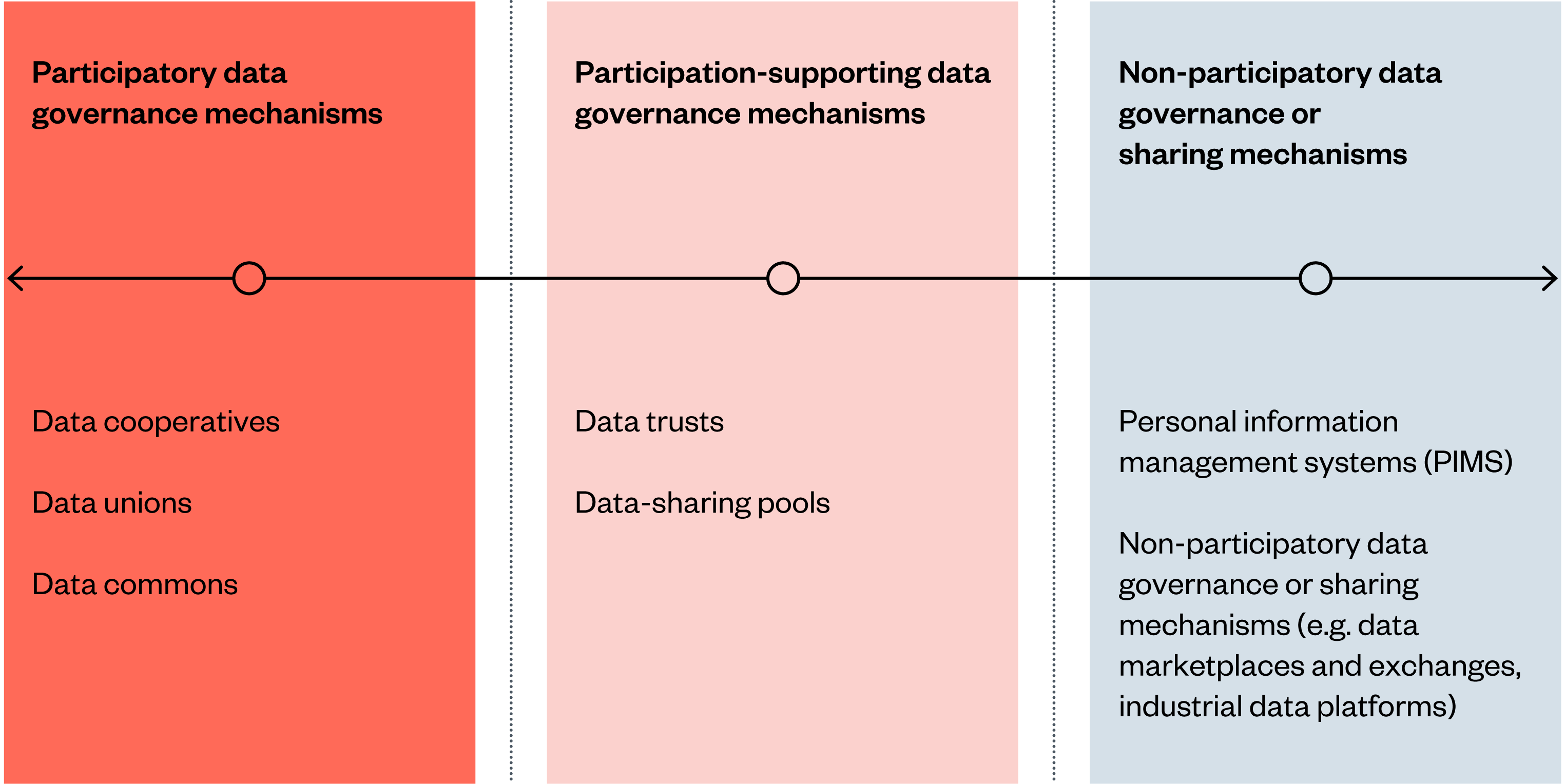

The three tables below illustrate the range of data governance mechanisms currently in use and their degree of participation.

- Table 1 shows mechanisms that are designed towards participation.

- Table 2 distinguishes ‘participatory supporting’ mechanisms, meaning mechanisms that allow and can be optimised for increased participation if participants wish to have higher levels of engagement.

- Table 3 lists non-participatory mechanisms, which nevertheless represent options for more choice over data management or increased data sharing.

Figure 1: Overview of data governance mechanisms

The following definitions for data trusts, data cooperatives, personal information management systems (PIMS) through to data-sharing pools are based on Ada’s work,[73] and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s map of data intermediaries.[74] The remaining definitions build on the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (now Responsible Technology Adoption Unit) independent report on data intermediaries[75] and other relevant scholarship.[76] [77] [78] [79]

Note that there is not currently a mapping of participatory mechanisms to mechanisms of inclusion, but that participatory mechanisms are not inherently inclusive, and can create conditions in which groups or communities feel excluded or disconnected from each other, as well as creating communities in which people feel included.[80]

Table 1. Participatory data governance mechanisms

Data cooperatives, data unions and data commons mechanisms are all intrinsically participatory mechanisms, working with or initiated by data subjects and designed to involve them collectively in decision-making about the holding and use of their data. These mechanisms tend to be aligned with outcomes relating to collective or public benefit.

| Data governance type | Definition | Governance mechanisms | Participatory mechanisms |

| Data cooperatives | A cooperative is an established legal mechanism, typically formed where there are collective interests that are better pursued jointly rather than individually. Cooperatives can take many different legal forms depending on the jurisdiction: for example, under UK law, there is no specific definition of a cooperative. The most widely used form is a cooperative society, but they can also be set up as a private company limited by shares or a private company limited by guarantee. The legal form will depend on the level of liability members are willing to expose themselves to, and the way members want the cooperative to be governed.

Data cooperatives are emerging intermediary structures where data is stewarded for the benefit of its members as individual data subjects (who might also see their interests as benefitting wider society). |

Data cooperatives are a decentralised form of data intermediary owned and run by members. Membership is open and voluntary, with an equal number of votes and the benefit is shared among its members. It is an autonomous and independent form of governance where data is stewarded in the collective interest of its members, and depending on the chosen governance form, it can advance the interests of all members at once, and/or it might be chartered to achieve consensus over whether an action is allowed.

|

Data cooperatives are highly participatory, allowing individual data subjects to have a direct say in how data is used and governed, steering its use according to their motivations, preferences and concerns.

If a new ecosystem of data cooperatives were created, this would create differentiation and choice for data subjects. |

| Data unions | A data union is a proposed new mechanism for data stewardship: a type of intermediary that positions itself between its members and the data platforms on which they perform economic activity (for example, Uber, Airbnb and similar entities). Data subjects grant the union (the intermediary) the exclusive right to use the data generated through the platforms. In a data union regulatory structure, platforms would not be entitled to access user data as it would be deposited in a union. To access data it would have to negotiate terms of access with the union.

Note that data unions are emerging, for example, Workers Info Exchange, but because of adverse conditions in the ecosystem they are not yet able to reach maturity as a collective representation model. |

A union is a formalised governance framework organising people (normally workers) for collective bargaining and representation. Data unions transfer the democratically governed labour union model into a data context. Unions could have regularly elected leadership that implement the policy goals of the union. They could be organised by geography or by policy, and funded through fees for access to data.

Note: the model presented here is distinct from the model of a formalised, decentralised governance framework that enables individuals to join together, control and potentially monetise their data – for example, people can contribute driving data to a data union, to be sold to insurance or mapping services. |

Data unions are highly participatory. Participation can take the form of collective gatherings for voicing opinions and setting terms, and representatives can be delegated to negotiate and act on member’s behalf. Data unions can allow communities to decide their own data policies, for example, currently marginalised communities. |

| Data commons | A data commons is an emerging mechanism: a collective set of resources that are governed based on economist Elinor Ostrom’s principles.

A data commons is a community that collectively and sustainably governs data. This may be motivated by sharing data between organisations (such as researchers) to collectively solve problems, or may go beyond problem-solving into sharing languages and cultural understanding (such as Indigenous communities).[81] A data commons implies that the body of (data) resources would grow or decline independently from the number of stakeholders and their individual data. This model assumes the commons will support community or societal benefits. |

Data commons are informal structures, with organisation through social norms and institutional arrangements. Data commons can have different governance arrangements, which negotiate individual and collective entitlements over data as resources that are placed under common control.[82]

|

Data commons can be highly participatory, and enable different degrees of participation in a data commons can be flexible, with members of the community getting involved as much or as little as they wish and have capacity to do so. |

Table 2: Participation-supporting data governance mechanisms

Data trusts and data-sharing pools can be more or less participatory, depending on specific governance choices: some trusts or pools will choose to empower data subjects to participate collectively in all aspects of governance and decision-making, while others will establish rules, norms or ways of working collaboratively at the outset and not require further substantial input. Their outcomes and objectives can be more or less aligned with collective or public benefit.

| Data governance type | Definition | Governance mechanism | Participatory mechanisms |

| Data trusts | A trust is an established legal mechanism under common law where assets (including data rights) can be placed under the control of a trustee who manages these assets on behalf and for the benefit of its beneficiaries/parties creating the trust. Data trusts are an emerging mechanism, where the exercise of data rights is the asset placed in trust by data subjects or data holders.

|

Data trusts allow individual data subjects or data holders to pool data rights and proactively determine the terms of use in accordance with their objectives and intentions (including to support wider public interest) as a way to rebalance some of the power asymmetries in today’s digital environment. Central to its governance are fiduciary obligations to ensure trustees act in the best interests of the parties creating the trust. It may borrow elements of equity law for creating an accountability framework.

|

Data trusts can be highly participatory, requiring systematic input from data subjects / holders, or can delegate responsibility to the trustee to determine what is beneficial for their interests. The trust’s founding charter may include mechanisms for deliberation and consultation with its beneficiaries / parties creating the trust.

Some research distinguishes public data trusts. In public data trusts, public bodies take on the role of trustees to steward citizens’ data. They may also take on a specific role in informing policymaking, public-service provision and innovation.[83] |

| Data-sharing pools | Data-sharing pools are alliances among data subjects and holders that share data with the aim of improving their assets (data products, processes and services). These alliances of organisations develop around a shared purpose, context or application, and are intended to benefit all participants. Examples include the Emergent Alliance initiative which aimed to aid societal recovery post COVID-19. | Data-sharing pools are a decentralised form of data intermediary that operate under contractual law. There is no single model: specific technical, legal and organisational structures are developed to support cooperation and coordination towards the agreed purpose(s) of the pool. Specific governance mechanisms for access to and uses of data held in the pool are defined through contractual means. Competition law considerations might be built into the data sharing agreements to protect against anti-competitive behaviour. | Data-sharing pools can be highly participatory, building in participatory governance mechanisms in which members exercise an equal stake in the organisation and its management, or can delegate responsibility for decision-making.

Like data cooperatives, if a new ecosystem of data-sharing pools were created, this would create differentiation and choice for data subjects. |

Table 3. Non-participatory data governance or sharing mechanisms

These mechanisms are inherently neither participatory nor inclusive, but are included here to present a full picture of the possible mechanisms for data stewardship. Personal information management systems (PIMS), data marketplaces, exchanges and industrial data platforms provide mechanisms for controlling or exchanging data that do not enable collective decision-making or require consideration of public benefit outcomes. PIMS are designed to support individuals to better manage and control their data, while marketplaces, exchanges and industrial platforms are designed to enable frictionless data sharing between organisations, normally without consideration or involvement of data subjects.

| Data governance type | Definition | Governance mechanism | Participatory mechanisms |

| Personal information management systems (PIMS) | PIMS are an emerging data governance mechanism, through data management service providers: technologies developed to offer data subjects a means to leverage control of the processing of their data. Their aim is to provide an alternative approach to data processing by increasing the possibility for individuals to exercise their data rights and manage decisions over their data (for example, consent management decisions over data access and specific uses, data portability) | PIMS usually come under the form of an application or a dashboard with no direct governance participation from individual data subjects. | Individuals are empowered to make more granular decisions over their data and have a say over who has access, when and under what conditions. This is a form of exercising agency and autonomy over data expressed primarily through technical controls.

At the technical platform level there is usually no opportunity for participation in how the technical tools are developed, aside from potential co-design and user feedback consultations at the developers’ discretion. |

| Non-participatory mechanisms for data-sharing | Data marketplaces: platforms that offer intermediation as part of a value-add service that matches the supply and demand of data or data products and services. These platforms act as ‘neutral intermediaries’ in data flows as (i) they do not actively intervene in data value chains but solely facilitate the matching of supply and demand, and (ii) the data intermediation service is open to any third party that respects the terms and conditions of the intermediary and the legal framework.

Data exchanges: Operate as online data platforms where datasets can be advertised and accessed – commercially or on a not-for-profit basis. Industrial data platforms: Provide shared infrastructure to facilitate secure data sharing and analysis between companies. |