Financial regulation in the UK

A case study

31 October 2024

Reading time: 59 minutes

This work was commissioned as part of our report on lessons for AI regulation from the governance of other high-tech sectors. There are two other case studies:

Introduction

This case study considers five research questions, that reflect active areas of discussion about developing a regulatory framework for artificial intelligence (AI). In applying these research questions to the established regulatory framework for banks, we provide a basis for drawing lessons for designing AI regulation. To add value to this discussion, the study focuses on how financial services regulation maintains stability and promotes the safety and soundness of UK banks. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has identified UK financial stability as a ‘global public good’.[1]

Five research questions about banking regulation, to help inform discussion on the design of AI regulation:

- What are the objectives of UK banking regulation?

- What mechanisms do regulators implement to meet their soundness and stability objectives with regards to the banking sector?

- How does a regulatory focus on financial stability and the safety and soundness of banks and the banking system facilitate the creation of public benefits?

- How are liability and compliance burdens – from regulation to promote soundness and stability of banks and the banking system – distributed across the value chain?

- How effective is UK banking regulation in achieving its soundness and stability objectives for the banking system?

The role of the financial industry as part of the UK economy and impact on society

The UK’s financial and insurance services contributed £173.6 billion to the UK economy

in 2021, 8.3% of the total. It is the fourth largest domestic industry, accounting for 9% of gross value added,[2] [3] and the fourth largest in comparison to other countries.[4] [5] The sector creates 3% of all jobs and contributes 4.1% of all taxes. Its economic benefit is unequally distributed across the UK, with around half of the sector’s output generated in London.[6]

The sector has a major influence over the rest of the economy as a facilitator of lending and investment activities across the whole economy. It provides huge systemically important infrastructures, without which the economy couldn’t function, and is an integral element to the UK’s standing on the world stage.

UK banks play a central role supporting day-to-day economic activity and supporting long-term growth. The sector plays a vital role in the basic functioning of the financial system, allowing households and businesses to finance purchases and investment. It does this by accepting short-term deposits and making loans at longer maturities, for example, through current account deposits and mortgage loans.[7] The sector involves retail, and wholesale and investment banks:

- Retail banks. Commonly known as ‘high street banks’, retail banks offer the basic banking needs of an individual, household or business. Services include: providing payments systems and the transfer of funds between accounts; providing deposit-taking facilities and a store-of-value system; lending and helping customers to manage their risks and financial needs over time, for example, by providing borrowing and saving facilities.

- Wholesale and investment banks. Wholesale and investment banks typically serve large corporate customers, other financial institutions and governments. They provide a range of services including arranging financing, trading, advising and underwriting. An investment bank may also undertake trading using its own capital in a variety of financial products, such as derivatives, fixed income instruments, currencies and commodities.[8]

The nature of banking means that banks have a much higher ratio of debt to shareholders’ capital than non-financial firms, allowing them to lend money and offer financing. The banking sector is also highly interconnected, resulting in the possibility that the failure of one or more can directly harm others and potentially, the entire banking system. In addition, all banks are vulnerable to a generalised lack of confidence in financial institutions that limits the availability of liquidity and funding. This can lead to a ‘bank run’, where customers all withdraw their money at the same time. These are manifestations of systemic risk: the risk of significant disruption to the financial system as a whole, exacerbated by dependencies and interconnections between financial institutions and markets.[9]

History of banking regulation

The UK has a rich history of banking with the City of London as a global hub. This reputation has its genesis in the Financial Revolution of the late 17th century which led to the creation of national debt and the establishment of the Bank of England to raise taxes for war:[10] the first example of regulatory intervention in financial services in England.[11]

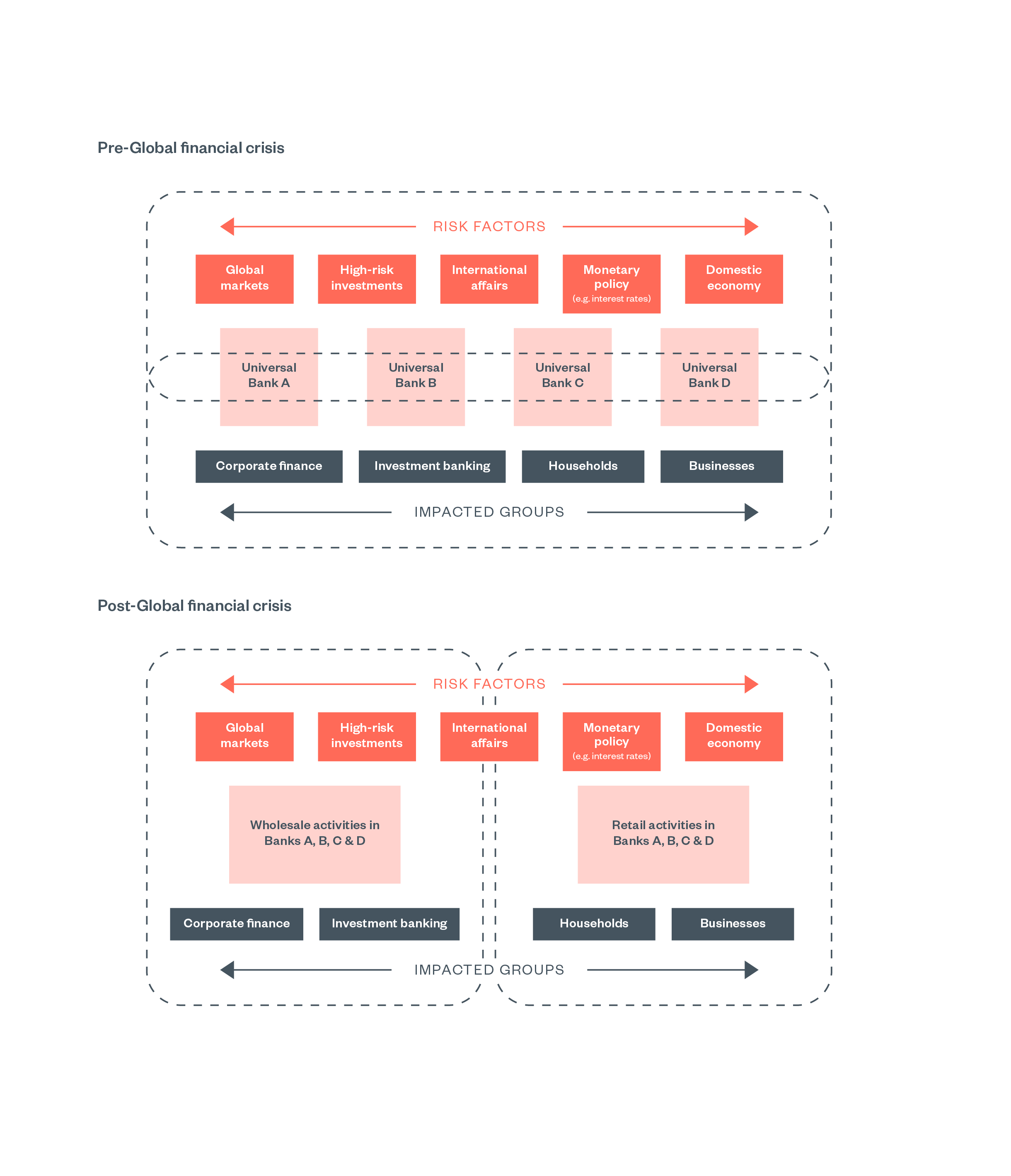

A combination of regulation, often the result of banking crises, and global economic activity has shaped UK banking over the 20th and 21st century. This has been influenced by developments in other countries, in particular the USA, where legislation introduced to restore safety and confidence in the sector following the 1929 stock market crash was rewritten over time and several elements repealed.[12] In particular, the removal of the separation between retail and investment banks led to the creation of globally competitive ‘universal banks’ with a large product offering and appetite for risk.[13]

In the late 20th century there was a competitive environment between countries vying to have the largest financial sector. The UK engaged in a process of deregulation that picked up pace in the 1970s, which intended to place London as world leader across a whole range of financial markets through the universal bank model. This enabled banks to diversify into new activities such as fund management, derivatives trading and general insurance to a global market. This model is celebrated by some for creating efficiencies through economies of scale, spreading fixed costs over a larger volume of output and risk diversification through capital pooling.

However, the evidence to support this view is sparse.[14] Beyond a certain size there may even be diseconomies of scale, possibly due to the complexity of managing large institutions.[15] Another important development during this period was the demutualisation of building societies. A change in legislation in 1986 allowed building societies (member-owned institutions first focused on guarding savings and mortgage lending) to convert into banks and start providing a wider range of services. This legislative change was intended to increase the size and competitiveness of UK financial services, but has also allowed financial institutions to become more complex and concentrated. Since 1995, seven of the ten largest building societies have converted.[16]

Deregulation placed the UK at the heart of global finance with nine UK banks occupying places in the FTSE 100 Index in 2007.[17] UK banks became so large and complex that the economic and social cost associated with their failure would be catastrophic. This resulted in the banks being regarded as ‘too big’ or ‘too important to fail’, meaning that if they did then the UK Government would have little option but to intervene to support them.[18]

The global financial crisis of 2007–8 demonstrated the complexity and interconnectedness of finance and the consequences of lighter-touch regulation. The regulatory framework failed to identify the problems that were building up in the financial system due to a focus on supervising individual banks, rather than the stability of the system as a whole. This enabled risky behaviour and the selling of bad products which, due to the interconnectivity of the sector, led to consequences felt by businesses and households across the globe.[19]

The impact in the UK saw the first run on a British bank in 150 years following reports that Northern Rock needed emergency support from the Bank of England. Northern Rock was one of the building societies that converted after the 1986 legislative change and grew into the fifth-largest bank in the UK by mortgage assets, relying heavily on funding from short-term debt.[20] Between 2007 and 2009, the Government made a number of interventions to support the banking sector at an estimated cost of £1.2 trillion, the majority used to buy shares in UK banks, such as RBS, HBOS and Lloyds TSB, and took full control of Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley.[21] Of the nine UK banks that once occupied the FTSE 100 Index, five ended up partly or wholly in public ownership.

The large size of the financial sector relative to the rest of its economy means that financial crises can have a particularly severe impact in the UK. The global financial crisis led to the deepest recession in terms of lost output since quarterly gross domestic product (GDP) data was first published in 1955.[22] This, along with the ensuing public spending cuts, the largest since the Second World War, saw living standards for those already in poverty worsen.[23], [24] Over 15 years later average wages remain £14,000 below where they would have been based on the rate of growth before the global financial crisis.[25]

The aftermath of the global financial crisis

The failure to identify the problems that were building up in the financial system meant that firms that were considered sound on an individual basis were actually exposed to stresses in other institutions and the aggregate behaviour of financial market participants.[26] The lack of focus on systemic stability enabled risky behaviour and the selling of bad products (mortgages on the retail side and the spreading of toxic debit on wholesale markets) which led to severe global consequences.

Legislative reforms to the UK’s financial regulatory framework 2009–2019 intended to improve overall safety by addressing the lack of resilience and consumer protection in the financial system. In particular, they aimed to reduce solvency and liquidity risk, which had combined to infect the global system and caused the run on banks like Northern Rock.

Solvency risk

The risk that a bank cannot meet its maturing obligations (that is, debt for which it is liable) because it has negative net worth.

Liquidity risk

The risk that a bank will not be able to meet its short-term payment obligations, either because it is not able to accrue enough funding on the wholesale market (funding liquidity), or because its securities or investments cannot be sold quickly enough to get an adequate market price (market liquidity).[27]

The direction of such reforms was set at an international level through the Basel Framework, set by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Since 1988 these measures have set minimum capital requirements for international banks, to improve the stability of the sector and maintain confidence in bank solvency. In response to the global financial crisis, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision published an update to its framework, Basel III, in 2010, which strengthened measures to improve the sector’s ability to absorb shocks from financial and economic stress, reducing the on the wider economy and expense to the taxpayers. This has resulted in the introduction of capital buffers, higher capital requirements for particularly risky products and global minimum liquidity requirements.[28] Basel III is expected to be implemented by all jurisdictions by 2025.

In the UK, successive governments embarked on a legislative process that overhauled the UK’s regulatory architecture, institutions, mandates, objectives and powers. Notable reforms include:

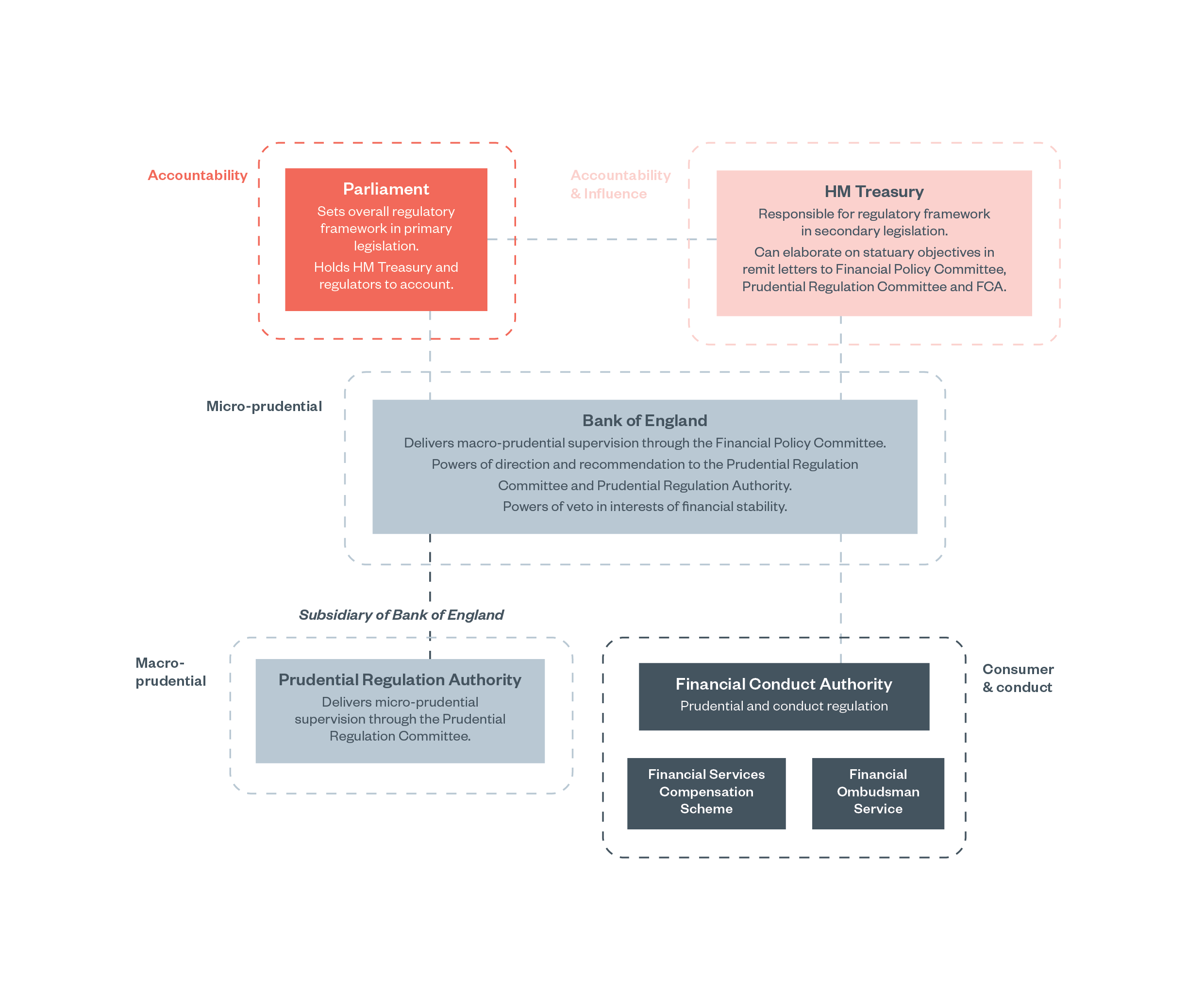

- The creation in 2001 of the Financial Ombudsman Service to resolve consumer complaints and the Financial Services Compensation Scheme that protects up to £85,000 in personal and business deposits if a bank fails.[29] [30]

- The creation of the Financial Policy Committee in 2011 in the Bank of England with primary statutory responsibility for maintaining financial stability.[31]

- The abolition of the Financial Services Authority, criticised for a too-broad remit and for relying on ‘tick-box’ compliance.[32]

- The creation of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in 2013, with a remit to regulate market conduct and protect consumers.

- The creation of the Prudential Regulatory Authority in 2013. A new subsidiary of the Bank of England, bringing macro- and micro-prudential regulation from the Financial Services Authority and into a single institution.[33]

- The separation (‘ringfencing’) of retail and investment banking activities to insulate critical banking services from shocks elsewhere in the financial system.[34]

Figure 1: Banking before and after ringfencing rules

Objectives of UK banking regulation

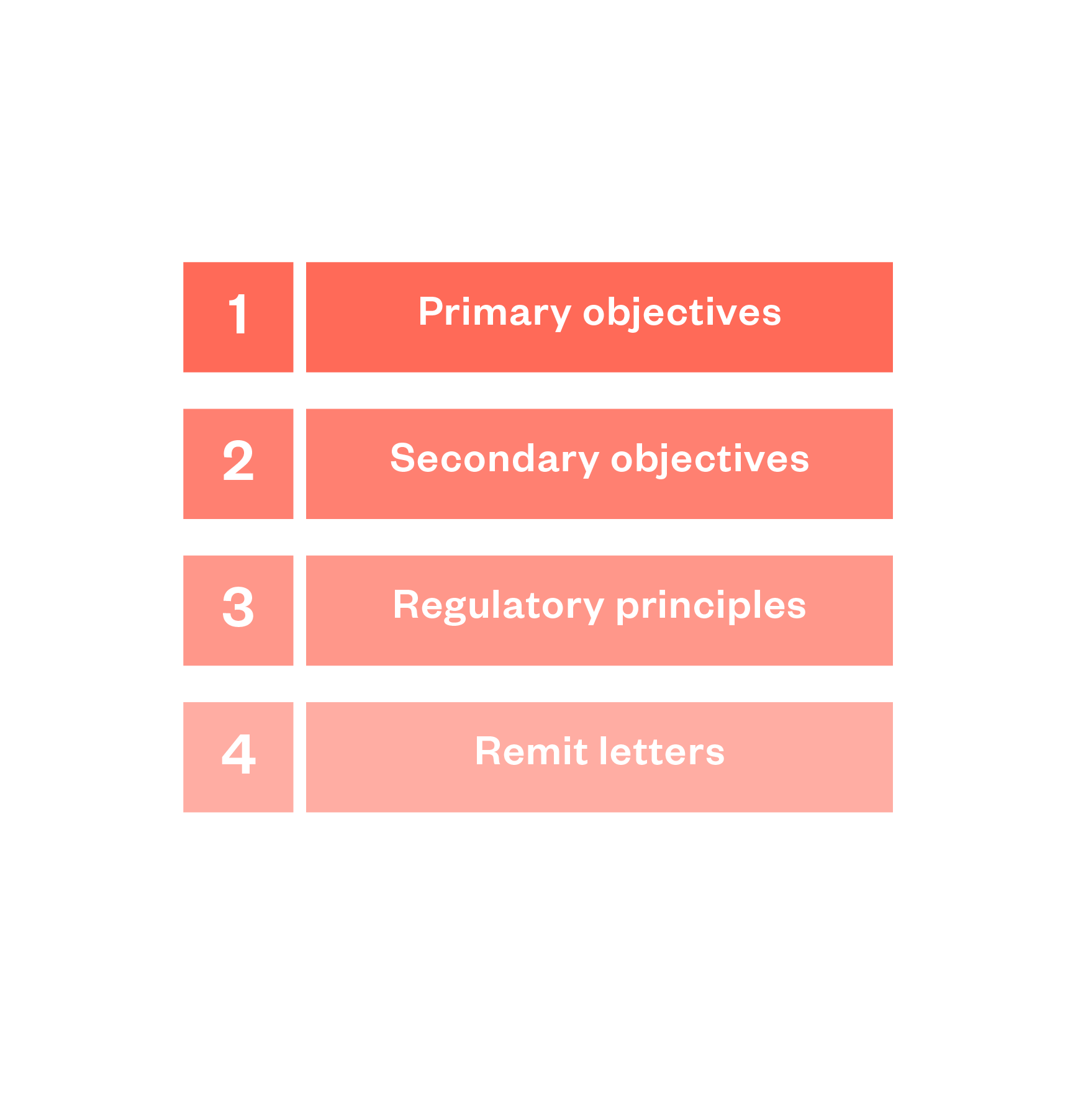

The Bank of England, the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority are operationally independent regulators required by law to act in a way that advances their statutory objectives when carrying out their general functions. Parliament sets these objectives and gives them the powers and duties to pursue them. Under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2023, the regulators are empowered to make decisions independently, however, Parliament has the right to require them to explain and justify decisions. HM Treasury is responsible for the regulatory framework and secondary legislation, and is empowered by Parliament to elaborate on statutory objectives in remit letters.[35]

Statutory objectives

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the UK’s central bank. It has two primary objectives: price stability and maintaining financial stability. It has a secondary objective to support the Government’s economic policy, including its objectives for growth and employment.[36]

Prudential Regulation Authority

The Prudential Regulation Authority has a general objective to promote the safety and soundness of approximately 1,500 banks, building societies, credit unions, insurers and major investment firms. It also has an objective that specifically relates to insurance firms, to contribute to ensuring that policyholders are appropriately protected. It has two secondary objectives: 1) to facilitate effective competition in the markets; 2) to facilitate the international competitiveness of the UK economy and its growth in the medium- to long-term.[37]

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)

The FCA’s strategic objective is to ensure that financial markets function well. Its operational objectives are to secure an appropriate degree of protection for consumers, protect and

enhance the integrity of the UK financial system, and to promote effective competition in the interests of consumers. It also has the same secondary objective as the Prudential Regulation Authority to facilitate international competitiveness and growth. The FCA regulates the conduct of approximately 45,000 businesses, prudentially supervises approximately 44,000 firms and sets specific standards for approximately 17,000 firms.[38]

Definition of the consumer

The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 defines consumers as person who:

- ‘use, have or may use a regulated financial service or services provided by other than authorised persons but are provided in carrying on regulated activities

- have relevant rights or interests in relation to any of those services

- have invested, or may invest, in financial instruments

- have relevant rights or interests in relation to financial instruments

- have rights, interests or obligations that are affected by the level of a regulated benchmark.‘[39]

Operational independence

The Bank of England and the FCA are operationally independent regulators, as is the Prudential Regulation Authority as a subsidiary of the Bank of England. The Bank of England was granted independence in the Bank of England Act in 1998. The FCA’s independence is guaranteed in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. The Treasury is responsible for the appointment of senior leaders (see ‘Relationships with the stakeholders’ section).

Regulatory principles

In pursuing their objectives, the regulators must take into account regulatory principles that capture a wider set of public policy considerations. When pursuing objectives, the regulators must ‘have regard’ (take into account) their regulatory principles and identify which are significant to the proposed policy. They then judge, on a case-by-case basis, the extent to which the principle should influence the outcome, with some being more significant than others.

Regulatory principles [40] [41]

1. Efficiency and economy

2. Proportionality

3. Sustainable growth

4. Climate change and environment[42]

5. Consumer responsibility

6. Senior management responsibility

7. Recognising differences in business

8. Openness and disclosure

9. Transparency.

In addition to the above, the FCA has a perimeter (remit), set by the Government and Parliament, that determines the activities they regulate, and the level of protection consumers can expect when they buy financial services and products. In its annual Perimeter Report, the FCA defines which financial services activities require firms to be authorised by the FCA. This is discussed and agreed with the Government.[43]

Remit letters

Legislation empowers the Treasury to make recommendations to each regulator at any time on issues related to matters of economic policy through recommendation letters (also known as remit letters). The Treasury can at any time make recommendations to the Prudential Regulation Authority and the FCA, at least once per Parliamentary session, regarding regulatory principles. Similarly, it can make recommendations to the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee but these can go wider than matters it should ‘have regard to’. For example, the Treasury may make recommendations to the Financial Policy Committee about ‘the responsibility of the FPC in relation to support for the economic policy of the Government, including its objectives for growth and employment’.[44] All regulators are required to respond, setting actions taken or intended and, if appropriate, reasons why they do not intend to act. For example, in 2022/23, the Treasury wrote to both the Financial Policy Committee and FCA to ask how they intended to support the Government’s objective to promote the international competitiveness of the UK.[45] [46] Both responded and outlined how they would achieve this in line with their objectives.[47] [48]

Figure 2: Order of regulatory mandate

Relationship with the stakeholders

Government

Ministers and officials meet regularly with the regulators to discuss policy issues and areas of joint work or interest, while recognising the regulators’ operational independence. The Treasury is also responsible for appointing senior roles including the Governor of the Bank of England; the Chair and the Chief Executive of the FCA; at least three members of the FCA’s governing body; and at least six members of the Prudential Regulation Committee.[49]

Parliament

The regulators are subject to scrutiny by Members of Parliament through the cross-party Treasury Select Committee, which regularly questions senior regulators on matters of policy and can run public inquiries.[50] The Treasury Sub-Committee on Financial Services Regulations scrutinises regulatory changes.[51] Members of the House of Lords scrutinise the regulators in a similar way through Select Committees for example, Economic Affairs Committee.[52]

Industry and end users

The regulators regularly publish policy positions for public feedback, acting as the main channel to hear stakeholder views. The policy positions are published in several forms:

- consultation papers

- discussion papers

- supervisory statements

- policy statements

- calls for input

- guidance documents on changes to handbook guidance.[53] [54]

In addition, several panels represent stakeholder views and engage directly with the regulators.

Financial Services Consumer Panel

An independent statutory panel that represents the interests of consumers and small businesses. They provide advice and challenge to the FCA in relation to its statutory duties in particular its consumer protection objective.[55]

Practitioner Panel

A statutory panel that includes representatives from the banking industry to consider Prudential Regulation Authority policies and practices to help it meet its statutory objectives.[56]

Cost Benefit Analysis Panels

Statutory panels of experts provide advice to the Bank of England, the Prudential Regulation Authority and the FCA to analyse and estimate, where possible, the likely impacts of a policy on different groups such as industry, consumers and markets. This informs and refines the policy approach to identified issues, helping to design approaches that are most net beneficial.[57] [58]

Funding

The FCA collects fees and levies from regulated firms to finance their work and that of the Prudential Regulation Authority, the Financial Ombudsman Service and the Financial Services Compensation Scheme. The fee is different for each firm and is calculated based on the type of regulated activities, the extent of their activities and the cost to regulate them.[59] The Bank of England and the Prudential Regulation Authority are funded by a combination of the Bank of England Levy and the cost of regulation.[60]

Figure 3: Map of relevant organisations for financial regulation in the UK

Maintaining stability and promoting the safety and soundness of UK banks

The stability, safety and soundness of UK banks is achieved through a combination of macro- and micro-prudential supervision regimes, which cover systemic and individual risk respectively.[61] Combined with conduct and consumer protection regimes, this approach builds on the lessons from the global financial crisis.

Macro-prudential

Macro-prudential regulation ensures that the financial system as a whole is stable, and therefore safe and sound, by identifying, monitoring and mitigating systemic risks. Even when firms are considered stable on an individual basis, the aggregate behaviour of firms can seriously damage the stability of the financial system. This is overseen by the Bank of England Financial Policy Committee .

The Financial Policy Committee identifies, monitors and takes action to remove or reduce systemic risks with a view to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system. It meets four times per year and publishes its views of the risks to the UK’s financial system and how to tackle those risks. Twice per year (Q2 and Q4) they also produce a more detailed Financial Stability Report that sets its view on the stability of the UK financial system and what it’s doing to remove or reduce any risks.

When a potential risk to financial stability has been identified, the Financial Policy Committee can act in the following ways.

- Power of direction. Binding instructions it can give to the Prudential Regulation Authority and the FCA.

- Power of recommendation. Make recommendations on a ‘comply or explain’ basis to the Prudential Regulation Authority and to the FCA. The Financial Policy Committee can also make general recommendations to other bodies.[62]

Micro-prudential

Micro-prudential regulation ensures the safety and soundness of individual firms, safeguarding individual financial institutions from specific risks and preventing them from taking too much risk. This is overseen by the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Prudential Regulation Committee.

The Prudential Regulation Authority creates policy for firms to follow, that is enacted through the Prudential Regulation Authority Rulebook. These rules require firms to maintain sufficient capital and have adequate risk controls in place. The Prudential Regulation Authority also supervises firms, to ensure that they have a comprehensive overview of their activities so they can step in if necessary. For example, banks must ensure they meet the Threshold Conditions at all times in order to carry out regulated activities. In addition to the Threshold Conditions, there are eight Fundamental Rules that apply proportionately to all Prudential Regulation Authority-regulated firms, taking into account the differences between sectors and between sizes of firms.

The Threshold Conditions

Minimum requirements that firms must meet at all times to be permitted to carry on the regulated activities in which they engage.

Fundamental Rules

High level rules that collectively act as an expression of the Prudential Regulation Authority’s general objective of promoting the safety and soundness of regulated firms. A failure to comply may result in enforcement or other actions.[63]

Consumer protection

The FCA regulates the conduct of the firms it supervises by making new rules and issuing guidance and standards. Under these methods it ensures accountability for employee behaviour and that products and services are implemented with a consumer focus.

In regulating products and services, the FCA (and the Prudential Regulation Authority) do not pre-authorise products or services and rely on a combination of ex-ante and ex-post powers to maintain high standards and consumer safety. The challenge for this type of regulation is to intervene at the correct time.[64] The FCA does offer limited support and guidance for products and services but this is limited and only applicable to those deemed innovative.

Ex ante

For example, firms (including their business models) are authorised; employees are fit and proper; rules and guidance on interacting with consumers are followed.

Ex post

For example, monitor data and social media for suspicious behaviour or activity; update guidance; complain to the Financial Ombudsman.

Mechanisms to maintain stability and promote the safety and soundness of UK banks

Capital and liquidity positions

Following standards set at international level, the Basel III reforms require banks to hold a certain level of capital that can absorb losses. This aims to reduce the risk to creditor and depositor holdings. For example, major UK banks must maintain a level of Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio, assets that can absorb losses immediately when they occur. At the end of 2023, this was at 15.9%.[65]

Banks must also hold an adequate quantity of sufficiently liquid assets. To achieve this, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) promotes the short-term resilience of the liquidity risk profile of banks. Major UK banks have a current LCR of around 146%; small and medium banks have an aggregate of LCR of 260%. In addition, banks must also maintain a net stable funding ratio (NSFR) to ensure they maintain a stable funding profile over a longer horizon in relation to the composition of their assets and off-balance sheet activities.[66]

Capital and liquidity positions are monitored by the Financial Policy Committee, and the Bank of England releases quarterly reports on the sector’s regulatory capital. These measures reduce risky behaviour and ensure that banks are able to withstand market shocks, both domestically and internationally, without placing consumer deposits, or taxpayer funds, at risk.

In addition to these, the Financial Policy Committee also sets a rate for a countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB), the level of additional cushion of capital that banks need to have to absorb potential losses. This allows the Financial Policy Committee to adjust the resilience of the UK banking system to the changing risks it faces over time. This is a direct response to the global financial crisis and liquidity risk, providing extra capital if a bank faces losses. If the Financial Policy Committee thinks that risks to financial stability are growing, it will set a higher CCyB rate (currently – spring 2024 – at its neutral setting of 2%).[67]

Stress testing

Stress testing is an integral part of maintaining stability and protecting consumers. This requires cross-regulator collaboration that occurs through a system-wide exploratory scenario. The explanatory scenario aims to improve understanding of the behaviours of banks and non-bank financial institutions in stress conditions, and how these behaviours might interact to amplify shocks in UK financial markets that are core to UK financial stability.

Annual stress tests of the UK banking system, carried out under the guidance of the Financial Policy Committee (and Prudential Regulation Committee), inform the setting of capital buffers. Known as the annual cyclical scenario, they measure the resilience of UK banks to a hypothetical, countercyclical scenario that includes a severe but plausible combination of adverse shocks. Banks are assessed to check if they have sufficient resilience to continue supporting households and businesses in the face of such shocks. This provides an opportunity for them to enhance their resilience if needed. For example, the hypothetical scenario used in 2022/23 involved persistently higher advanced-economy inflation, increasing global interest rates, deep and simultaneous recessions in the UK and global economies, and sharp falls in asset prices. The results suggested that banks would be resilient to a global recession, including severe stresses to property prices.[68] In the most recent Financial Policy Committee Financial Stability Report, it was noted that property prices were falling in many countries but the result of the recent annual cyclical scenario informed the view that UK financial stability was not at risk.[69]

These tests involve the largest UK banks and building societies. Firms that are not part of this annual stress test must carry out their own stress testing. The Prudential Regulation Authority publishes a scenario every six months to serve as a guide for banks and building societies designing their own scenarios.

Every other year, the Bank of England and the Prudential Regulation Authority run the biennial exploratory scenario. This is an additional scenario intended to probe the resilience of the banking system to risks that may not be neatly linked to the financial cycle (for example, risks from climate change).[70]

Resolution regime

The Bank of England is also the UK’s Resolution Authority and has a process to ensure that if a UK bank or building society fails it makes sure that this happens in an orderly way and that losses arising are borne by shareholders and unsecured creditors. This limits the disruption to vital services, removes the need for public investment, protects people’s money and incentivises banks to operate more prudently.

It is empowered to use the following tools to achieve this:

- Bail-in: write-down of the claims of the bank’s unsecured creditors (including holders of capital instruments) and conversion of those claims into equity as necessary to restore solvency to the bank.

- Transfer to a private sector purchaser: the transfer of all or part of a bank’s business, which can include either its shares or its property (its assets and liabilities), to a willing and appropriately authorised private sector purchaser without need for consent of the failed bank, or its shareholders, customers or counterparties.

- Transfer to a bridge bank: the transfer of all or part of the bank’s business to a temporary bank controlled by the Bank of England.[71]

In June 2022, the Bank of England published the findings from its first assessment of the resolvability of the eight major UK banks as part of the Resolvability Assessment Framework. This assesses their ability to enter resolution safely, defined as remaining open and continuing to provide vital banking services to the economy.[72]

Resolution regime in action

The resolution regime was tested in 2023 with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank , headquartered in the USA but with a small presence in the UK that concentrated on the innovation sector. The Bank of England’s resolution regime ensured that in less than 72 hours Silicon Valley Bank UK was sold to HSBC, to guarantee the continuity of deposits and the promotion of public confidence in the financial system. The pace and process was commended by the Financial Stability Board (a body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system.)[73]

The Bank of England sets the preferred resolution strategy for all firms and works with them to ensure that any impediments to an orderly resolution are addressed. This includes engagement with the Financial Services Compensation Scheme which protects eligible depositors, up to certain limits, in the event of firm failure where relevant.[74]

Conduct

The FCA and Prudential Regulation Authority enforce the Senior Managers and Certification Regime, an individual accountability regime. Launched in 2016 it consists of three key elements:

- Senior Managers Regime: Senior Managers hold one or more roles designated as Senior Management Functions. The individuals holding such roles are the firm’s most senior individuals. These include executive roles, such as chief executives and finance directors, as well as some oversight roles, such as chairs of boards and their sub-committees and senior independent directors.

- Certification Regime: covers functions at the firm that are not Senior Management Functions and that have a material impact on risks to customers and the risk profile of the firm.

- Conduct Rules: these set minimum standards of conduct for all professional employees, together with additional rules applicable to Senior Managers. (See below.)[75]

Conduct Rules

Individual conduct rules (apply to almost all staff at firms, including senior managers):

- Act with integrity.

- Act with due skill, care and diligence.

- Be open and cooperative with the FCA, the Prudential Regulation Authority and other regulators.

- Pay due regard to the interests of customers and treat them fairly.

- Observe proper standards of market conduct.[76]

Senior Manager conduct rules – in addition to above:

- Take reasonable steps to ensure that the business of the firm is controlled effectively.

- Take reasonable steps to ensure that the business of the firm complies with the relevant requirements and standards of the regulatory system.

- Take reasonable steps to ensure that any delegation of responsibilities is to an appropriate person.

- Disclose appropriately any information of which the FCA/Prudential Regulation Authority would reasonably expect notice.[77]

The Senior Managers and Certification Regime is designed to operate in a preventative manner. However, the regulators can take action to enforce the rules. This can include any, or all, of the following:

- A public censure.

- A financial penalty.

- A suspension, condition, or limitation in relation to an individual’s approval.

Where the FCA or the Prudential Regulation Authority determines that an individual is not fit and proper, they may withdraw their approval for the individual to hold a Senior Management Function.[78]

Consumer protection

In July 2023, the Consumer Duty came into force. This sets higher and clearer standards of consumer protection across financial services and requires firms to put their customers’ needs first. The duty includes a sixth individual Conduct Rule requiring all staff to ‘act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers’ where the activities of the firm fall within the scope of the duty. The rules require firms to consider the needs, characteristics and objectives of their customers – including those with characteristics of vulnerability – and how they behave, at every stage of the customer journey. As well as acting to deliver good customer outcomes, firms will need to understand and evidence whether those outcomes are being met.

The duty applies to products and services offered to retail customers, including bank deposits, credit, mortgages and investments. It applies across the distribution chain, from product and service origination through to distribution and post-sale activities. This means that all firms involved in the manufacture, provision, sale and ongoing administration and management of a product or service to the end retail customer are covered.[79] The enforcement approach will be proportionate to the harm to consumers and will involve interventions or investigations, along with possible disciplinary sanctions.[80]

The duty complements guidance issued by the FCA for firms on the fair treatment of vulnerable customers, defined as ‘someone who, due to their personal circumstances, is especially susceptible to harm, particularly when a firm is not acting with appropriate levels of care’. Their guidance includes actions that banks should take to ensure they treat vulnerable customers fairly.[81]

Outcomes expected by firms under the Consumer Duty.[82]

- Consumers to have confidence in retail financial services markets, with healthy competition based on high standards and firms focused on delivering good customer outcomes.

- Vulnerable consumers to have outcomes as good as other consumers.

- Consumers to be sold products and services that are designed to meet their needs, characteristics and objectives.

- Consumers to get products and services which offer fair value.

- Consumers to understand the information they are given and make timely and informed decisions.

- Consumers to be provided with support that meets their needs.

Innovation

The FCA views innovation as a potential driving force behind competition and, when it works well, it can benefit consumers through lower costs, higher standards and quality, and increased access to financial services.[83] This supports its operational objective to promote effective competition in the interests of consumers. It also sees innovation as a facilitator for the financial services industry to contribute to economic growth, since 2023.[84] It supports the industry to achieve this through a combination of product development, regulatory guidance and when necessary, regulatory intervention.

The FCA has a range of innovation services that are designed to support firms at any stage of maturity, from collaboration, initial idea and proof of concept; to obtaining authorisation and scaling up in the market. In 2014 they launched Project Innovate to enable positive innovation in financial services markets.[85] There are several options available that have been developed since then that aim to support positive innovation to come to market in a controlled and sustainable way.[86]

Examples of FCA innovation services

Regulatory Sandbox[87]

Allows firms to test their business models in the live market with real consumers.

Digital Sandbox[88]

A testing environment that enables us to support firms at the early stage of product development by enabling experimentation through proof of concepts.

TechSprints[89

Events that bring together participants from across and outside of financial services to address industry challenges. Previous TechSprints have, amongst others, explored the issues of consumer access, cryptoassets, fraud, anti-money laundering and financial crime. In 2023 the FCA announced a Financial Inclusion TechSprint.

Innovation Pathways[90]

Support for firms to navigate financial regulation when developing a product that doesn’t fit into existing regulatory categories.

Effectiveness of this regulatory approach

Effective

Independence

Since 1998 operational independence of the Bank of England and regulators has been guaranteed in law in the UK. There is a body of evidence in support of independence which indicates that political interference has consistently caused or worsened financial instability, and independent regulators have increased the efficiency and effectiveness of regulation, as well as helped markets operate more smoothly and efficiently.[91]

Operational independence allows the regulators to take a long-term, independent view of risks and the measures needed to address them. It also underpins the stability and predictability of the UK’s regulatory regime, which helps make the UK an attractive place to do business for firms. The independence of supervisors from governments is one of the pillars of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision core principles for effective banking supervision and compliance to this principle is regularly assessed by the IMF and the World Bank.[92]

In combination with Parliamentary accountability, it safeguards against the aggressive pursuit of ideological or political agendas. However, politicians and the Treasury do not always respect this independence: recently, an attempt to implement greater influence via a new ‘call-in’ power, to enable the Treasury to make, amend or revoke regulators’ rules, was dropped following Parliamentary scrutiny.[93]

Stability

The primary stability objective and macro-prudential regime has had successes and avoided a repeat of major crises thus far. Stability, safety and soundness of the financial system has been well maintained in the face of global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit, as well the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine and rising interest rates. According to the IMF, the UK’s financial stability framework is well positioned to address vulnerabilities. It has also called the Financial Policy Committee a ‘world-class macroprudential authority’ and commended the transparent approach to regulation, as well as seamless data-sharing between the Bank of England, Prudential Regulation Authority and FCA.[94] A 2022 independent review of the ringfencing regime, separating retail and investment banking activities, has been effective in safeguarding everyday banking services from riskier activities.[95] However, the UK sector remains denominated by highly connected large institutions that are likely to be ‘too big to fail’ should another crisis hit. For example, the big four banks account for 65% of personal current accounts and 73% of business accounts.[96]

Globally, the banking sector remains prone to crises with hallmarks of the global financial crisis, suggesting that global regulatory standards may be supporting and maintaining a risky system, rather than reforming it. This was exemplified in the failure of Swiss bank Credit Suisse in 2023, which despite being a global systemically important bank[97] suffered severe liquidity outflows in a six-month period. This required government support of over $50 billion, and a quick sale to its rival UBS, to ensure financial stability in Switzerland and globally.[98] Post-global financial crisis regulation significantly reduced the impact of the bank’s failure but it has not stopped it from happening. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and others in the USA in 2023 also reminded us that significant banking crises can re-occur despite post-global financial crisis reforms.

Consumer protection

The Consumer Duty requires firms to make lasting changes to their culture and behaviour to consistently deliver good outcomes for consumers. This aims to build trust between the industry and consumer, producing good outcomes for consumer welfare, productivity and growth in the economy.[99] This builds on years of work and guidance from the FCA on how firms should approach vulnerable customers and conducting reviews to this effect.[100] It represents a trend towards outcomes-based regulation, as opposed to prescriptive regulation, with firms having to demonstrate that they are meeting the FCA’s expectations.

In regulating complex, critical areas, such as financial services, it has become necessary for regulators to outline what constitutes good behaviours and outcomes, in addition to detailed rules and guidance. It is too early to determine the success of this approach but an FCA report in February 2024 highlighted the following examples of good practice where firms have actioned the following:

- Increased focus on the customer at board level, with senior leadership teams giving serious consideration to what the duty means for them at a practical and cultural level.

- Examined whether the total cost to consumers of their products and services – including fees, charges and other costs – provides fair value relative to their benefits. Firms have made changes to improve their value proposition by reducing costs for consumers by updating pricing models for products and services.

- Considered the needs of customers with characteristics of vulnerability as part of product and service design.[101]

- Made positive changes to their product development processes, with greater focus on how new products will meet the needs of a specified target market and deliver good outcomes for them.[102]

Approach to innovation

The FCA is recognised as a global leader in its field and its proactive sandbox approach has reduced barriers to innovation whilst maintaining the same standards of regulation and consumer protection. It has provided approximately 300 UK firms with oversight and support and has been replicated across many jurisdictions.[103] A large majority (92%) of firms who have used the Regulatory Sandbox go on to become successfully authorised and 80% of firms that were tested in the sandbox are still in operation.[104] The FCA leads and chairs the Global Financial Innovation Network, with more than 70 organisations, that explores improving the relationship between firms and regulators as they innovate.[105]

Ineffective

There are several areas where it can be argued that the current approach to regulation is ineffective.

Risks out of regulatory scope

The success of regulation is limited by its parameters and in a large, complex and dynamic market there can be developments that sit outside of regulatory scope. For example, there is a risk to financial stability from non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs), institutions that are playing an increasingly important role in financing the real economy and in managing the savings of households and corporations.[106] Also known as ‘shadow banking’, these activities do not fall under the same regulatory requirements but may involve liquidity problems and the build-up of leverage in a global and highly connected market. This can result in the same combination of pre-global financial crisis activity that caused systemic failure and consumer harm.

The market is incentivised to, and will, grow outside of the regulatory perimeter. The growth of NBFIs is a prime example of this and the Bank of England has been criticised by the IMF and former staff for being slow to address it.[107][108] The Prudential Regulation Authority has recently opened a consultation on exploring how banks can set limits to exposures from NBFIs,[109] finally falling in-line with Basel Committee on Banking Supervision guidelines set in 2017 for implementation in 2020. This risk can be seen in other areas of finance, such as the rise of the Buy Now Pay Later market, which has quadrupled in size since 2020 and risks placing vulnerable consumers into unmanageable debt. Despite this rise, the product largely remains outside of the FCA’s regulatory perimeter.[110]

Oversight and coordination

In common with the nature of banking, the wider regulatory landscape for financial services is interconnected and complex. It involves several separate regulators with specific responsibilities for different elements of the sector that are connected to banks, such as the Payments Systems Regulator and the Pensions Regulator. The Bank of England also looks at the financial market infrastructures such as Visa. Banks are also impacted by the actions of unregulated big tech firms who provide many essential and critical services such as cloud services. This leads to the possibility that banking regulators do not have sufficient oversight and coordination over the full suite of potential risks to financial stability and the safety and soundness of firms.

Limited nature of independence and principles-based regulation

While there are benefits to independence, there are also drawbacks. The nature of regulatory independence is limited given the use of remit letters by the Government to match their political aims, and the ability of the Government to determine senior appointments to regulatory boards. Specifically for the FCA, whose regulatory perimeter is set by the Government and Parliament, areas of priority can be overlooked, as has been the case with Buy Now Pay Later, which the FCA has recommended for full regulation since 2021.[111]

As witnessed recently, the Government can introduce new objectives that are arguably ideologically driven and controversial. The new secondary objective in 2023 for the Prudential Regulation Authority and the FCA to promote international competitiveness of the sector creates a conflict of interest for regulators who are now required to both regulate and promote the financial services sector.[112] [113] It should be remembered that these mandate to promote competitiveness, which was regarded as a driver behind the weak regulatory landscape in the lead-up to the global financial crisis and was subsequently removed from regulators remits.[114] This is also an example of the shortcomings of principles-based regulation, as the appropriateness of the principles is a subjective question.

Lack of institutional diversity and support for the whole economy

Post-global financial crisis regulatory reforms have failed to reform the banking system in important ways that can support financial stability and the economy. For example, as noted earlier, the sector remains dominated by large interconnected banks, the majority of which are shareholder-owned. This increases systemic risk, as evident by Credit Suisse, and reduces the opportunities for public purpose to drive the financial sector. As shareholder owned banks, their primary responsibility is towards their shareholders.

Alternative models, including cooperative banks, credit unions and publicly owned banks are very small in the UK.[115] [116] The current regime doesn’t have any mechanism to encourage a better diversity of institutions to reduce these risks. In Germany, by contrast, the banking sector is dominated by publicly and cooperatively owned banks and the top four private banks have only 16% of the market.[117] In the five years following the global financial crisis, UK bank lending to non-financial businesses fell by around 25%, while over the same period the German Sparkassen and co-operative banks increased their lending by around 20%.[118]

Failure to support the whole economy

The UK’s financial system is very large compared to its economy. London competes with New York for the title of the world’s largest international finance centre, despite the population of the UK being far smaller than the USA. A recent study calculated the total cost of lost growth potential for the UK caused by ‘too much finance’ between 1995 and 2015 to be around £4,500 billion, or about roughly 2.5 years of the average GDP across the period.[119] Part of this estimate is made up of the cost of crises,[120] but up to 60% of the estimate is due to ‘misallocation costs’ such as: a focus on short-termism and rent extraction rather than investment; brain drain; and price spillovers such as property price inflation. Despite its size, financial services provide just over 3% of all UK jobs: one percentage point less than the early 1990s.[121]

Influence of commercial interests

The financial services lobby is extremely powerful and has close association with the policymaking process. Financial institutions and individuals closely tied to the financial sector donated over £15 million to political parties in 2020 and 2021. Furthermore, business interests dominate public consultations relating to private finance, advocating for weaker financial regulation.[122] Additionally, while the Financial Services Panel is to be commended, it’s questionable as to whether it can be seen as representing all consumers[123] and is not replicated within the Bank of England or Prudential Regulation Authority. Broader public interests inevitably find it hard to muster as much lobbying power as concentrated financial sector interests, and the system does not provide much support for them to do so.

Footnotes

[1] IMF, ‘UK FInancial Sector Assessment Programme 2022’ (2022).

[2] Abbas Panjwani, ‘Industries in the UK’ (House of Commons Library 2023) <https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8353/CBP-8353.pdf>.

[3] In 2023 the largest contributor to economic output was real estate, followed by retail and wholesale and manufacturing. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8353/

[4] Behind Luxembourg, South Africa and Switzerland.

[5] ‘National Income – Value Added by Activity – OECD Data’ (OECD Data) <http://data.oecd.org/natincome/value-added-by-activity.htm> accessed 29 April 2024.

[6] Georgina Hutton, ‘Financial Services: Contribution to the UK Economy’ (House of Commons Library 2022) <https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06193/SN06193.pdf>.

[7] ‘Bank of England Market Operations Guide: Our Objectives’ (Bank of England) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/bank-of-england-market-operations-guide/our-objectives> accessed 29 April 2024.

[8] Independent Commission on Banking, ‘Interim Report: Consultation on Reform Options’ (2011) <https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20131202225058/http://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/htcdn/Interim-Report-110411.pdf>.

[9] ibid.

[10] John David Angle, ‘Glorious Revolution as Financial Revolution’ [2013] History Faculty Publications <https://scholar.smu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=hum_sci_history_research>.

[11] Richard Davies and Peter Richardson, ‘Evolution of the UK Banking System’ (2010) Q4 Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2010/evolution-of-the-uk-banking-system.pdf>.

[12] ‘Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) | Federal Reserve History’ (Federal Reserve History) <https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/glass-steagall-act> accessed 29 April 2024.

[13] Corinne Crawford, ‘The Repeal Of The Glass- Steagall Act And The Current Financial Crisis’ 9 Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER) <https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/268111481.pdf>.

[14] Davies and Richardson (n 11).

[15] Andrew G Haldane, ‘The $100 Billion Question’ (Bank of England 2010) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2010/the-100-billion-question-speech-by-andrew-haldane.pdf>.

[16] Jacqueline Cook, Simon Deakin and Alan Hughes, ‘Mutuality and Corporate Governance: The Evolution of UK Building Societies Following Deregulation’ (2002) 2 Journal of Corporate Law Studies 110.

[17] House of Commons Treasury Committee, ‘Banking Crisis: Dealing with the Failure of the UK Banks’ (House of Commons 2009) Seventh Report of Session 2008–09 <https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmselect/cmtreasy/416/416.pdf>.

[18] Davies and Richardson (n 11).

[19] Edmonds, ‘Financial Crisis Timeline’ (House of Commons Library 2010) Briefing Paper <https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04991/SN04991.pdf>.

[20] Hyun Song Shin, ‘Reflections on Northern Rock: The Bank Run That Heralded the Global Financial Crisis’ (2009) 23 Journal of Economic Perspectives 101.

[21] Frederico Mor, ‘Bank Rescues of 2007-09: Outcomes and Cost’ (House of Commons Library 2018) Briefing Paper <https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN05748/SN05748.pdf>.

[22] House of Commons Treasury Committee (n 17).

[23] Tax and welfare changes between 2010-2014 meant that the poorest two-tenths of the population saw greater cuts to their net income than every other group,

[24] Krisnah Poinasamy, ‘The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality: UK Case Study’ (Oxfam 2013) <https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/cs-true-cost-austerity-inequality-uk-120913-en_0.pdf>.

[25] Camron Aref-Adib and others, ‘Putting the 2024 Spring Budget in Context’ (Resolution Foundation 2024) Briefing <https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2024/03/Back-for-more.pdf>.

[26] HM Treasury, ‘The Financial Services Bill: The Financial Policy Committee’s Macro-Prudential Tools’ (HM Treasury 2012) Command Paper Cm8434.

[27] Raja Almarzoqi, Sami Ben Naceur and Alessandro Scopelliti, ‘How Does Bank Competition Affect Solvency, Liquidity and Credit Risk? Evidence from the MENA Countries’ (IMF 2015) IMF Working Paper WP/15/210 <https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp15210.pdf>.

[28] Basel Committee and on Banking Supervision, ‘Basel III: A Global Regulatory Framework for More Resilient Banks and Banking Systems’ (Bank for International Settlements 2010) <https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf>.

[29] Financial Ombudsman Service, ‘Who We Are’ (Financial Ombudsman) <https://www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk/who-we-are> accessed 29 April 2024.

[30] Financial Servcies Compensation Scheme, ‘What We Cover’ <https://www.fscs.org.uk/what-we-cover/> accessed 29 April 2024.

[31] HM Treasury, ‘The Financial Services Bill: The Financial Policy Committee’s Macro-Prudential Tools’ (n 26).

[32] HM Treasury, ‘A New Approach to Financial Regulation: Judgement, Focus and Stability’ (HM Treasury 2010) Command Paper Cm 7874 <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/81389/consult_financial_regulation_condoc.pdf>.

[33] ibid.

[34] RFPT Independent Review, ‘Final Report’ (2022) <https://rfpt.independent-review.uk/uploads/CCS0821108226-006_RFPT_Web%20Accessible.pdf>.

[35] HM Treasury, ‘Financial Services Future Regulatory Framework Review: Proposals for Reform’ (2021) Consultation Paper CP 546 <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/618a4b9fe90e071977182bd5/FRF_Review_Consultation_2021_-_Final_.pdf>.

[36] Bank of England Act 1998.

[37] PRA, ‘The Prudential Regulation Authority’s Approach to Banking Supervision’ (PRA 2023) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/approach/banking-approach-2023.pdf>.

[38] FCA, ‘About the FCA’ (20 April 2016) <https://www.fca.org.uk/about/what-we-do/the-fca> accessed 29 April 2024.

[39] Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

[40] Financial Services and Markets Act 2000.

[41] HM Treasury, ‘Financial Services Future Regulatory Framework Review: Proposals for Reform’ (n 35).

[42] In accordance with section 1 of the Climate Change Act 2008 (UK net zero emissions target) and section 5 of the Environment Act 2021 (environmental targets).

[43] FCA, ‘Our Perimeter Report’ (2024) Annual Report <https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/annual-reports/perimeter-report> accessed 29 April 2024.

[44] HM Treasury, ‘Financial Services Future Regulatory Framework Review: Proposals for Reform’ (n 35).

[45] Jeremy Hunt, ‘Financial Policy Committee Remit and Recommendations: Autumn Statement 2022’ (17 November 2022) <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/remit-and-recommendations-for-the-financial-policy-committee-autumn-statement-2022/financial-policy-committee-remit-and-recommendations-autumn-statement-2022>.

[46] Jeremy Hunt, ‘Recommendations for the Financial Conduct Authority’ (8 December 2022) <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/639227cee90e0769b493a15e/FCA_Remit_Letter_December_2022_with_cover.pdf>.

[47] Andrew Bailey, ‘FPC Response to HMT’ (13 December 2022) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/letter/2022/december/2022-remit-response.pdf>.

[48] Nikhil Rathi, ‘Section 1JA Recommendations for the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)’ (20 July 2023) <https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/correspondence/fca-response-treasury-remit-letter-2023.pdf>.

[49] HM Treasury, ‘Financial Services Future Regulatory Framework Review: Proposals for Reform’ (n 35).

[50] UK Parliament, ‘Role Treasury Committee’ <https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/158/treasury-committee/role/> accessed 29 April 2024.

[51] UK Parliament, ‘Role of the Treasury Sub-Committee on Financial Services Regulations’ <https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/600/treasury-subcommittee-on-financial-services-regulations/role/> accessed 29 April 2024.

[52] UK Parliament, ‘Economic Affairs Committee’ (23 April 2024) <https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/175/economic-affairs-committee/> accessed 29 April 2024.

[53] FCA, ‘What We Publish’ (29 July 2016) <https://www.fca.org.uk/what-we-publish> accessed 29 April 2024.

[54] Bank of England, ‘Policy’ (22 April 2024) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/policy> accessed 29 April 2024.

[55] FCA, ‘Financial Services Consumer Panel’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/panels/consumer-panel>.

[56] Bank of England, ‘PRA Practitioner Panel Terms of Reference’ <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/about/prc/practitioner-panel-terms-of-reference.pdf>.

[57] Bank of England and PRA, ‘Panel Appointments: Statement by the PRA and the Bank of England’ (2023) Statement of policy <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/approach/panel-appointments-sop.pdf>.

[58] FC, ‘Cost Benefit Analysis Panel: Background’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/panels/cost-benefit-analysis-panel/background>.

[59] FCA, ‘Fees and Levies’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/fees>.

[60] Bank of England, ‘Governance and Funding’ (2024) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/about/governance-and-funding>.

[61] ECB, ‘Financial Stability Review’ (2014) <https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/fsr/financialstabilityreview201405en.pdf>.

[62] There’s no evidence of these powers being used recently. Powers of direction over PRA/ FCA have only been used once.

[63] PRA, ‘The Prudential Regulation Authority’s Approach to Banking Supervision’ (n 37).

[64] Interview with stakeholder.

[65] Bank of England, ‘Banking Sector Regulatory Capital – 2023 Q4’ (March 2024) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/banking-sector-regulatory-capital/2023/2023>.

[66] PRA, ‘DP1/22 – The Prudential Liquidity Framework: Supporting Liquid Asset Usability’ (2022) Discussion Paper <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2022/march/prudential-liquidity-framework-supporting-liquid-asset-usability>.

[67] Bank of England, ‘The Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB)’ (2024) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financial-stability/the-countercyclical-capital-buffer>.

[68] Bank of England, ‘Stress Testing the UK Banking System: 2022/23 Results’ (2023) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/stress-testing/2023/bank-of-england-stress-testing-results> accessed 30 April 2024.

[69] Financial Policy Committee, ‘Financial Stability Report’ (Bank of England 2023) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability-report/2023/financial-stability-report-december-2023.pdf>.

[70] Bank of England, ‘Stress Testing’ (2024) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/stress-testing>.

[71] Bank of England, ‘Resolution’ (2024) <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financial-stability/resolution>.

[72] Bank of England, ‘Resolvability Assessment of Major UK Banks’ <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability/resolution/resolvability-assessment-of-major-uk-banks.pdf>.

[73] Financial Stability Board, ‘2023 Bank Failures: Preliminary Lessons Learnt for Resolution’ <https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P101023.pdf>.

[74] PRA, ‘The Prudential Regulation Authority’s Approach to Banking Supervision’ (n 37).

[75] Bank of England, ‘DP1/23 – Review of the Senior Managers and Certification Regime (SM&CR)’ (2023) Discussion Paper <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2023/march/review-of-the-senior-managers-and-certification-regime>.

[76] FCA, ‘Conduct Rules’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/senior-managers-and-certification-regime/conduct-rules>.

[77] FCA, ‘Senior Managers Regime’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/senior-managers-and-certification-regime/senior-managers-regime#section-dual-regulated-firms>.

[78] Bank of England, ‘DP1/23 – Review of the Senior Managers and Certification Regime (SM&CR)’ (n 75).

[79] ‘FG22/5 Final Non-Handbook Guidance for Firms on the Consumer Duty’ (FCA 2022) Finalised Guidance <https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/fg22-5.pdf>.

[80] Sheldon Mills, ‘Countdown to the Consumer Duty’ (2023) <https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/countdown-consumer-duty>.

[81] FCA, ‘FG21/1 Guidance for Firms on the Fair Treatment of Vulnerable Customers’ (2021) Finalised Guidance <https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/fg21-1.pdf>.

[82] FCA, ‘Consumer Duty Implementation: Good Practice and Areas for Improvement’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/good-and-poor-practice/consumer-duty-implementation-good-practice-and-areas-improvement>.

[83] FCA, ‘Our Innovation Services’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/our-innovation-services>.

[84] Sheldon Mills, ‘How Innovation and Regulation in Financial Services Can Drive the UK’s Economic Growth’ (2023) <https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/how-innovation-and-regulation-in-financial-services-can-drive-uk-economic-growth>.

[85] FCA, ‘The Impact and Effectiveness of Innovate’ (2019) <https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research/the-impact-and-effectiveness-of-innovate.pdf>.

[86] FCA, ‘Our Innovation Services’ (n 83).

[87] FCA, ‘Regulatory Sandbox Accepted Firms’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/regulatory-sandbox/accepted-firms>.

[88] FCA, ‘Digital Sandbox’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/digital-sandbox>.

[89] FCA, ‘TechSprints’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/techsprints>.

[90] FCA, ‘Innovation Pathways’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/innovation-pathways>.

[91] Marc Quintyn and Michael W. Taylor, ‘Should Financial Sector Regulators Be Independent?’ Economic Issues <https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/issues/issues32/index.htm#:~:text=Bank%20regulatory%20independence%20is%20to,other%20sector%2Dspecific%20regulatory%20agencies.>.

[92] PRA, ‘The Prudential Regulation Authority’s Approach to Banking Supervision’ (n 37).

[93] House of Lords, ‘Making an Independent Bank of England Work Better’ [2023] Economic Affairs Committee.

[94] IMF, ‘United Kingdom: Financial Sector Assessment Program-Financial System Stability Assessment’ (2022) <https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/02/22/United-Kingdom-Financial-Sector-Assessment-Program-Financial-System-Stability-Assessment-513442>.

[95] RFPT Independent Review (n 34).

[96] FCA, ‘Strategic Review of Retail Banking Business Models: Annexes to the Final Report 2022’ (2022) <https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/multi-firm-reviews/strategic-review-retail-banking-business-models-annexes-final-report-2022.pdf>.

[97] FSB, ‘2022 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs)’ <https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P211122.pdf>.

[98] Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, ‘Report on the 2023 Banking Turmoil’ (BIS 2023) <https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d555.pdf>.

[99] Sheldon Mills, ‘What Firms and Customers Can Expect from the Consumer Duty and Other Regulatory Reforms’ (2022) <https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/what-firms-and-customers-can-expect-consumer-duty-and-other-regulatory-reforms>.

[100] FCA, ‘Review of Firms’ Treatment of Customers in Vulnerable Circumstances’ (2024) <https://www.fca.org.uk/news/news-stories/review-firms-treatment-customers-vulnerable-circumstances>.

[101] It is worth noting that the FCA does not have a formal regulatory role in promoting access and inclusion.

[102] FCA, ‘Consumer Duty Implementation: Good Practice and Areas for Improvement’ (n 82).

[103] Interview with stakeholder.

[104] Jessica Rusu, ‘Innovation & Regulation: Partners in the Success of Financial Services’ (2022) <https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/innovation-regulation-partners-success-financial-services>.

[105] FCA, ‘Global Financial Innovation Network (GFIN)’ (2023) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/global-financial-innovation-network#revisions>.

[106] FSB, ‘Non-Bank Financial Intermediation’ (2024) <https://www.fsb.org/work-of-the-fsb/financial-innovation-and-structural-change/non-bank-financial-intermediation/>.

[107] IMF (n 94).

[108] Laura Noonan, ‘Bank of England Accused of Failures on Shadow Banking’ FT (7 August 2022) <https://www.ft.com/content/284c2817-f888-4e56-9cb3-e74d8e18ec9c?list=intlhomepage>.

[109] PRA, ‘CP23/23 – Identification and Management of Step-in Risk, Shadow Banking Entities and Groups of Connected Clients’ (2023) Consultation Paper 23/23 23 <https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2023/december/stepin-risk-consultation-paper>.

[110] Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, ‘Guidelines: Identification and Management of Step-in Risk’ (BIS 2017) <https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d423.pdf>.

[111] FCA, ‘Our Perimeter Report’ (n 43).

[112] HM Treasury, ‘Financial Services: The Edinburgh Reforms’ (2022) <https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/financial-services-the-edinburgh-reforms>.

[113] Finance Innovation Lab, ‘Written Evidence Submitted by the Finance Innovation Lab’ <https://bills.parliament.uk/publications/48066/documents/2339>.

[114] APPG Fair Business Banking and Finance Innovation Lab, ‘Is Competitiveness an Appropriate Statutory Objective for a Conduct Regulator? Roundtable Discussion – Summary’ (2022) <https://financeinnovationlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/22.02.2022-Competitiveness-and-Financial-Regulation-Roundtable-Summary-1.pdf>.

[115] Gemma Bone Dodds, ‘Barriers to Growing the Purpose-Driven Banking Sector in the UK’ (Finance Innovation Lab 2020) <https://financeinnovationlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Purpose-Driven-Finance-Finance-Innovation-Lab-1.pdf>.

[116] For example, 59% of people use a credit union in the United States, compared with just under 5% in Great Britain.

[117] Bikal Dhungel, ‘Financial System of Germany’ (2010).

[118] Joe Ahern and Christina Bovill Rose, ‘A WPI Economics Report for the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Fair Business Banking’ <https://www.appgbanking.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Scale-up-to-Level-Up-Final-Report-for-the-APPG-on-Fair-Business-Banking_amended-2.pdf>.

[119] Gerald Epstein, Andrew Baker and Juan Montecino, ‘The UK’s Finance Curse? Costs and Processes.’ Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) <https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/143275/1/Baker%20The-UKs-Finance-Curse-Costs-and-Processes%20final.pdf>.

[120] For example, the global financial crisis led to an estimated £1.8 trillion in lost GDP for the UK by 2015 (compared with pre-crisis trends).

[121] Hutton (n 6).

[122] Positive Money, ‘The Power of Big Finance’ (2022) <https://positivemoney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Positive-Money-The-Power-of-Big-Finance-Report-June-2022.pdf>.

[123] Interview with stakeholder.

Image credit: DGLimages

Related content

New rules?

Lessons for AI regulation from the governance of other high-tech sectors