Carbon emissions regulation in the UK

A case study

31 October 2024

Reading time: 57 minutes

This work was commissioned as part of our report on lessons for AI regulation from the governance of other high-tech sectors. There are two other case studies:

Acronyms used in this paper

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy & Industry Strategy |

| CCA | Climate Change Act |

| CCC | Climate Change Committee |

| CCS | Carbon capture and storage |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CO2e | Carbon dioxide equivalent |

| COP | Conference of Parties (of the UNFCCC) |

| DECC | Department of Energy and Climate Change |

| Defra | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| DESNZ | Department for Energy Security & Net Zero |

| DLUHC | Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities |

| ETS | Emissions Trading System/Scheme |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board |

| MHCLG | Ministry for Housing, Communities & Local Government |

| Ofgem | Office of Gas and Electricity Markets |

| SECR | Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

Introduction

Emissions resulting from human activities have substantially increased atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases,[1] resulting in global warming and affecting weather and climate contexts across the globe. This has produced ‘widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people’, as a result of various events including sea level rises, heat extremes, increases in food- and water-borne diseases, and compromised urban infrastructure.[2]

The largest share and growth in gross emissions has stemmed from the combustion of fossil fuels and industrial processes, with 79% of all greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 coming from energy, industry, transport and building sectors, and 22% from agriculture, forestry and other land uses.[3]

Given the multi-sectoral and systemic character of greenhouse gas emissions, as well as their impacts, emissions regulation takes a necessarily different shape to that of, for example, financial services and pharmaceuticals. Climate change is not a sector but rather a phenomenon that will affect, or is already affecting, every aspect of our society and economy to some degree, and it is generated through processes that are embedded in activities across the economy.

Lessons for an approach to AI regulation

In this way, climate change mitigation and adaptation governance bears some resemblance to AI governance, as AI technologies are also increasingly integrated into everyday life and economic production. The need to reduce emissions from CO2 and other greenhouse gases holds the potential to foster new sectors involved in, among other areas, the production and distribution of renewable energy, electric vehicles and energy efficiency measures such as insulating buildings.

At the same time, just as AI regulation faces the challenge of governing the dominant major technology companies, emissions regulation must oversee incumbent actors in fossil fuel-producing and carbon-intensive sectors, which have outsized impacts on emissions and contributions to the UK economy. Similarly, although the trajectories of AI development and climate change are determined at a global level, the UK can play a leadership role in steering both along a path that minimises harm. The experience of emissions regulation provides important lessons for an approach to AI that works for people and society.

The Climate Change Act 2008

The governance of climate change in the UK is concentrated under the Climate Change Act (CCA) 2008. This requires the mitigation of climate change risks by reducing greenhouse gas emissions; and adaptation – the adjustments needed to address climate change impacts such as increased flooding and coastal change, water shortages and higher temperatures.[4]

This case study will focus on mitigation, the framework for reducing emissions, rather than adaptation. Mitigation forms the larger part of the Climate Change Act itself, is more universally applicable to all sectors within the UK, and has so far overseen more concerted action when compared with climate change adaptation.

The research questions asked in this analysis cover the objectives of emissions regulation under the Climate Change Act, implementation mechanisms, public benefit and impact on innovation and growth. The methodology used consisted of desk-based research, including a literature review and eight semi-structured interviews with experts drawn from academia, environmental civil society organisations, government and business. This was followed by a roundtable with eight participants covering the same areas of expertise.

The context for emissions reduction regulation

Globally, CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions have increased dramatically since the mid-19th century. During the Industrial Revolution, which heralded a transition from an agriculture-based to a manufacturing-based economy powered by fossil fuels, the UK became a leading contributor of global emissions.[5] Emissions resulting from domestic production processes continued to climb throughout the 20th century, peaking in 1972, though ‘imported emissions’ – resulting from the production of products manufactured abroad that are consumed in the UK – did not peak until 2007.[6]

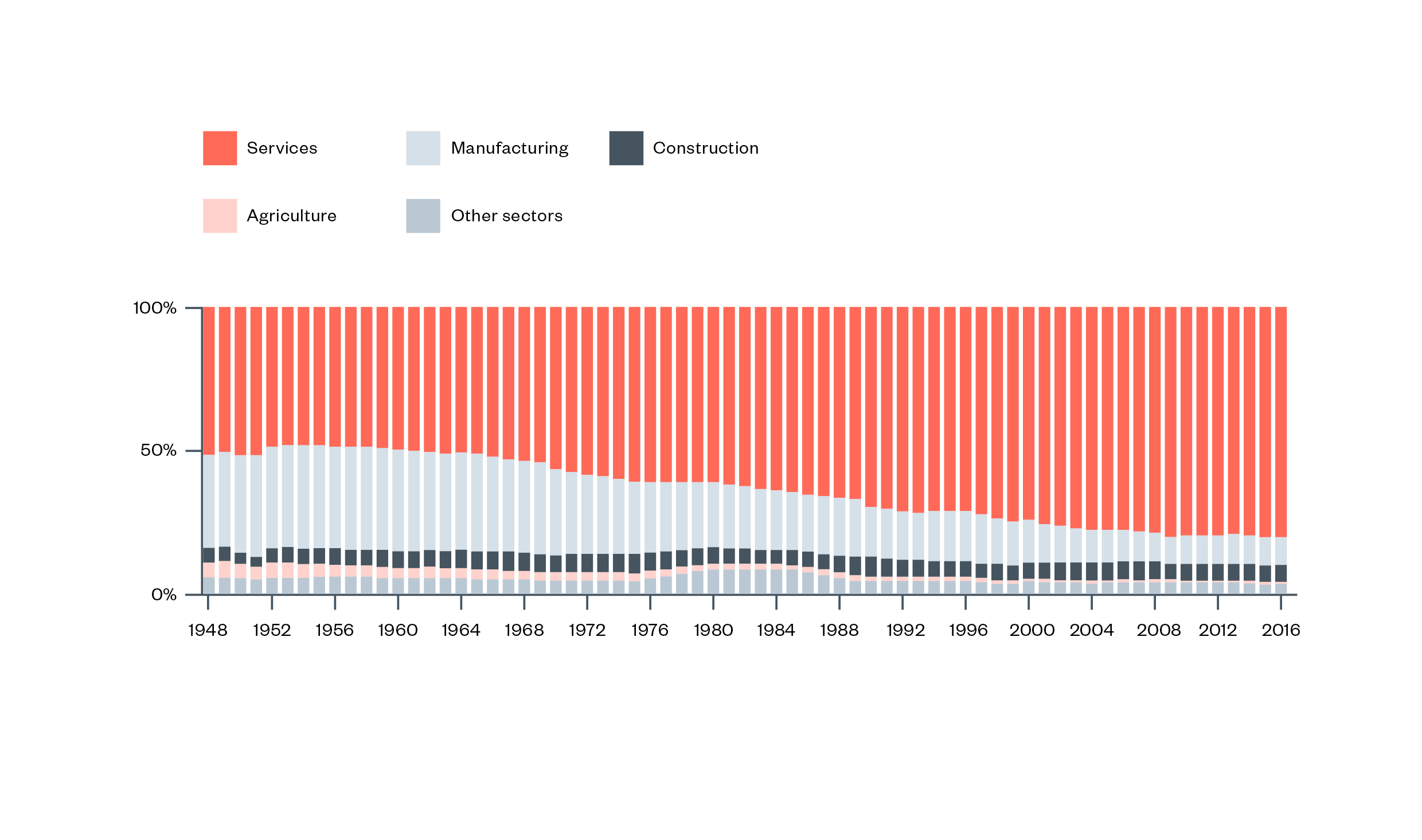

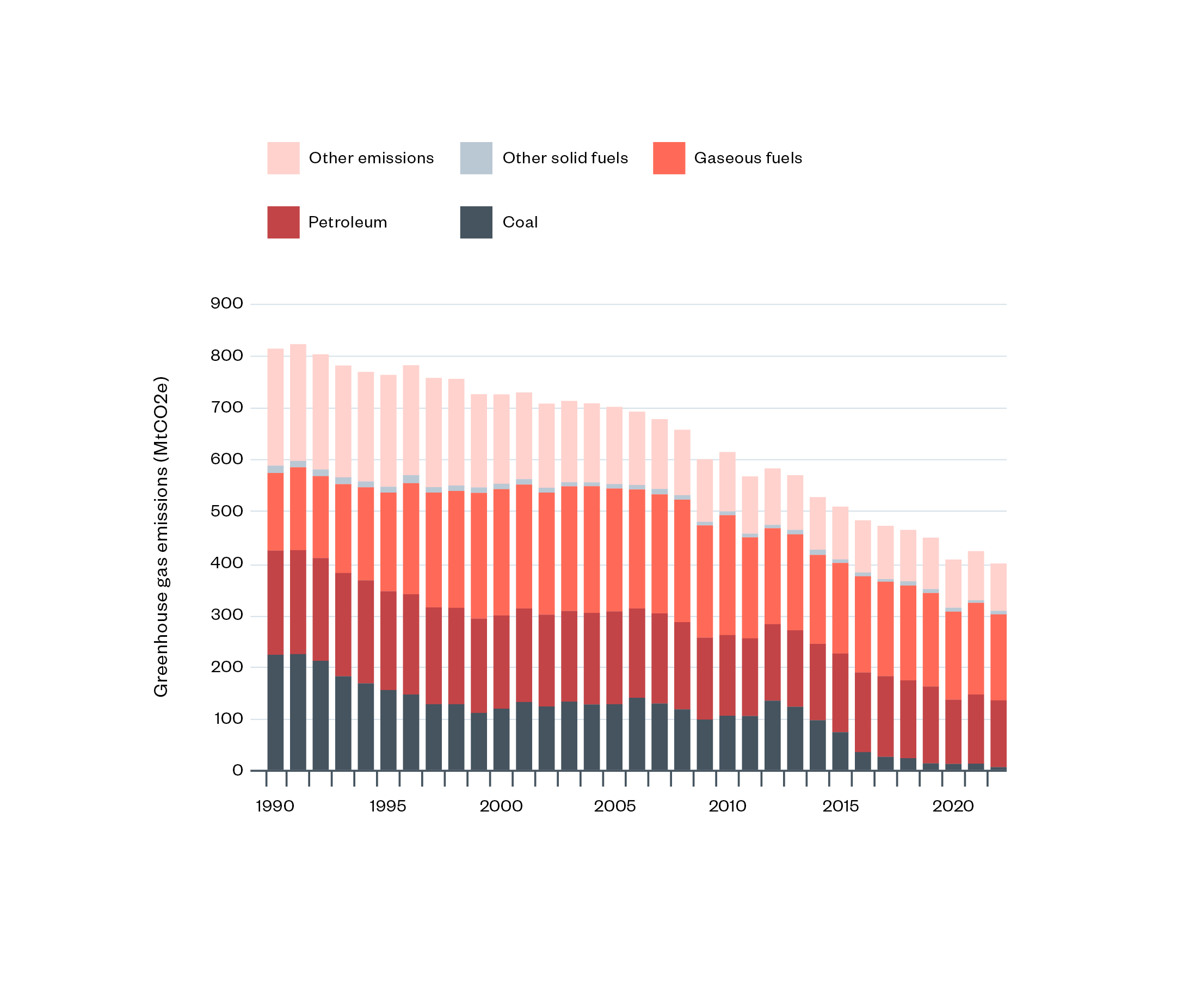

Between 1990 and 2022, Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions in the UK decreased by 46.2%.[7] The reduction of CO2e emissions during this period is associated with the continued structural transformation of the UK economy from manufacturing to service-based industries such as retail and hospitality, described in Figure 1 below, and significantly with the declining use of coal, as described in Figure 2. Today, the UK is the 17th largest emitter of GHG gases, based on territorial emissions, producing approximately 1% of the global total.[8]

Figure 1: Sectoral breakdown of UK economy, 1948–2016[9]

Figure 2: Territorial UK greenhouse gas emissions by fuel type, 1990-2022 (MtCO2e)[10]

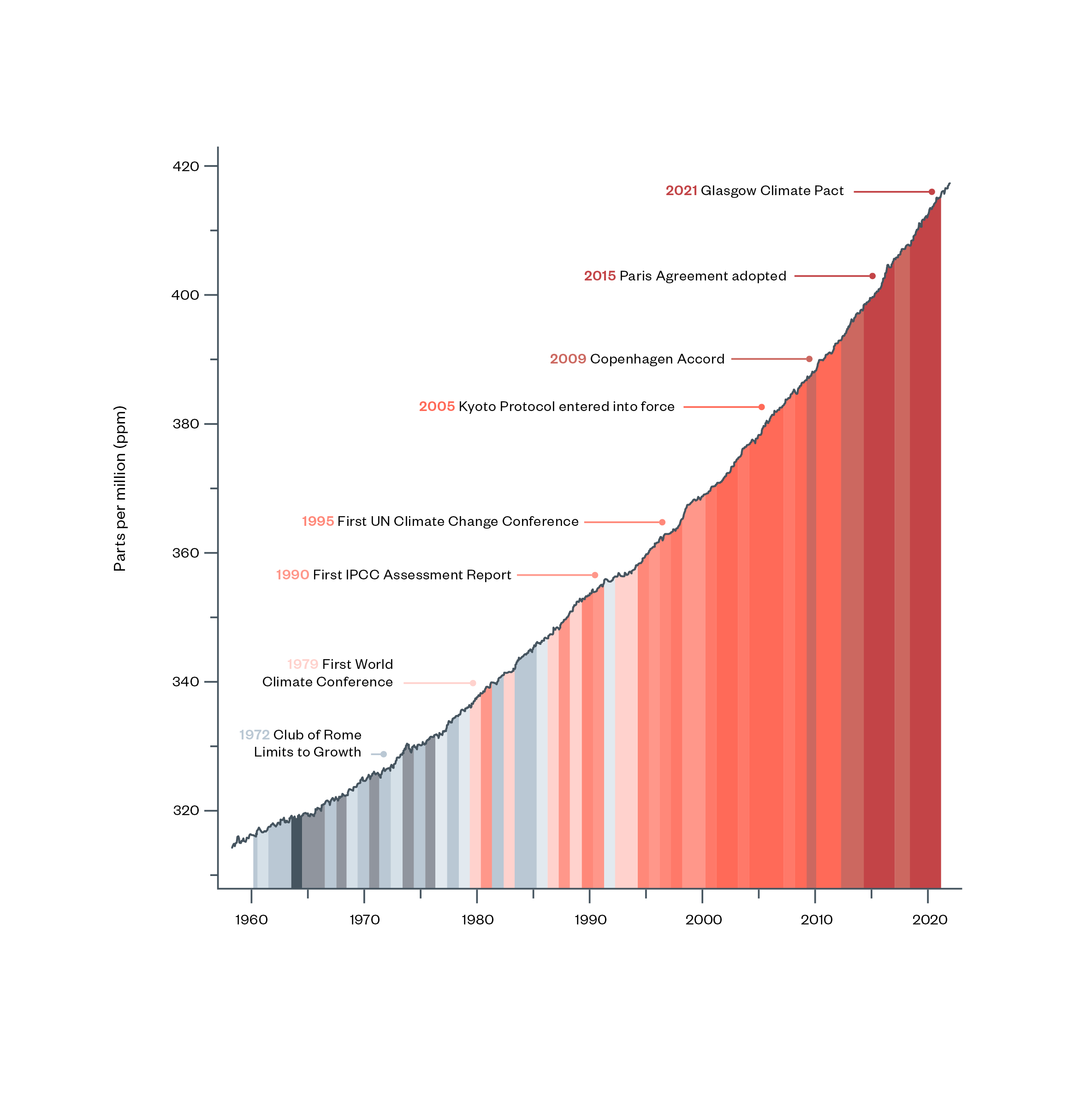

Scientists have observed and debated the relationship between concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere and global warming since at least the 1950s, and the first world climate conference was held in 1979. In the following years, climate change made its way out of scientific circles to become a major public and political concern, leading governments to assert control over the issue through the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which met for the first time in 1988.[11] The same year, the UN General Assembly issued its first resolution on climate change, endorsed the IPCC and established climate change as a priority issue for governments and others.[12] The IPCC’s First Assessment Report in 1990 laid the ground for the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was adopted in 1992 at what is known as the ‘Earth Summit’ in Rio de Janeiro. The first Conference of Parties (COP) met under the UNFCCC in 1995 and has met every year since.

One of the most controversial debates in the negotiation of the UNFCCC was about the inclusion of specific legally binding mitigation targets for developed countries. The US opposition to binding targets has shaped global climate governance ever since. The Kyoto Protocol ultimately included a binding target of a 5% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions below 1990 levels by 2012 for industrialised countries (later differentiated across ratifying states). This was far less than the 15% that the EU delegation – of which the UK was an active member – had pushed for by 2010, but was nonetheless seen as a diplomatic success.[13]

In a preview of the cycle that would animate US climate policy over the coming decades, the Republican government under George W Bush withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol, meaning it did not have enough countries to enter into force until Russia finally ratified it in 2004. Figure 3 shows how emissions have continued to rise since – and despite – the advent of an international climate governance regime, leading many to call for stronger mechanisms. The executive secretary of the UNFCCC itself noted that the radical change required to reduce emissions requires political responses to be ‘long, loud and legal’.[14]

Figure 3: Trends in atmospheric CO2 versus global temperature change[15]

Adoption of the UK Climate Change Act (2008)

The UK was an early and active player in the development of a global climate governance regime, with Margaret Thatcher endorsing an international framework in a speech at the UN General Assembly in 1989, and an initial Climate Change Programme was launched in 1994. The UK ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 1998 under which it committed to a 12.5% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions based on 1990 levels (the EU as a bloc had committed to 8%, which was distributed across Member States according to national circumstances). The UK target was well within reach due to the earlier ‘dash for gas’, which saw newly privatised electricity companies generating power increasingly through gas rather than coal.

The 1997 Labour Party manifesto committed the party to a higher voluntary target of 20% and the incoming government consequently introduced a new Climate Change Programme in 2000, projecting a 19% cut by 2010. By 2003, it became clear that delivery of this goal was off-track, despite an ambitious energy white paper and the stated commitment of Prime Minister Tony Blair. According to an Institute for Government review, the failure of these early initiatives lay in their structure and implementation: crucially, the responsible government department, the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), was unable to persuade other departments (notably those covering transport, industry and buildings) to take measures necessary to meet the 2010 target.[16] The failure of this non-binding and policy-based approach to result in significant climate action laid the ground for the Climate Change Act.[17]

The Institute for Government identified four key factors which came together to produce the political environment required for the Climate Change Act to go ahead: an active civil society campaign; political competition from the opposition in the form of the David Cameron, the new ‘green’ leader of the Conservative Party; the emergence of the economic case for mitigating climate change; and an engaged government ‘owner’ – the incoming Defra minister David Miliband.[18]

In 2005, Tony Blair used the G8 Summit at Gleneagles to urge the world’s top emitters to act, warning that failure to do so would be ‘deeply and unforgivably irresponsible’.[19] At the same time, Friends of the Earth led a campaign involving over 100 non-governmental organisations (NGOs): ’The Big Ask’. The campaign asked MPs to support a Private Members’ Bill, tabled by three MPs from the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties, requiring year-on-year reductions in emissions of 3%, leading to an 80% reduction by 2050.

‘The Big Ask’ built on an uptick in public concern, which had developed partly in response to the European heatwave which caused tens of thousands of deaths in 2003. Large membership NGOs, like the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and regular media coverage of the impact of climate change also boosted awareness and activity. Momentum was also spurred by the UK Government-commissioned Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change (2006), which made the economic case for decarbonisation, concluding that timely and effective action could cost around 1% of Gross Domestic Product while continuing inaction could reach between 5% and 20% annually.[20]

The Big Ask ultimately garnered cross-party support, with the Conservative Party committing to introduce a Climate Change Bill if elected. To determine the UK Government’s response, an Office of Climate Change was established, hosted by Defra but with cross-departmental ministerial oversight and cross-government funding, ‘avoiding the interdepartmental wrangling which had best the Climate Change Programme process’.[21] The momentum behind a legislative approach led to the Government publishing its draft Bill in March 2007.

The Bill initially set an emissions reduction target of 60% by 2050, based on the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution’s recommendation in 2000.[22] However, later research, and the accelerating rate of emissions, led environmental organisations to push for a strengthened target of 80% by 2050. The Big Ask campaigned on this, as well as on annual emissions targets and the inclusion of emissions from aviation and shipping. The Conservative Party also called for targets to be set annually, rather than every five years, fearing that the latter ‘will enable responsibility for failure to be shunted on from one government to another’[23], a fear that has arguably been borne out. Furthermore, the Shadow Environment Secretary wanted the Climate Change Committee (an independent, statutory body, previously named the Committee on Climate Change) to be empowered beyond its advisory capacity to set legal emissions reduction targets.

The 2050 target was a key recommendation of the Climate Change Committee, which was established in shadow form before the Climate Change Act’s passage, enabling the UK Government to draw on its advice as the Bill progressed. There was also active buy-in from business representatives, with the establishment of the Corporate Leaders Group in 2005 and the Confederation of British Industry’s 2007 Climate Change taskforce report, which pushed for climate action and for measures to ensure investor certainty throughout a transition.[24] The UK Parliament passed the Climate Change Act in November 2008 with an overwhelming majority (only five MPs voted against). There were some dissenting voices outside Parliament, including the early UK Independence Party, but overall the Act benefited from strong support across parties and devolved administrations. This reflected a period of unusual political consensus: according to Fankhauser et al, ‘it is unlikely that the same Act could have passed with the same level of unanimity at any other point in time over the past 10 years’.[25]

Although the Climate Change Act enshrined climate commitments in law for the first time, it was preceded by a regulatory infrastructure that included data gathering capacity and a dedicated regulator in the Environment Agency, established in 1996, which was more focused on immediate environmental harms. According to one interviewee for this study who was involved in developing the Climate Chage Act, these were ‘building blocks without which the Climate Change Act could not have been built’. The Act also intersected with EU and other international frameworks, notably the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) established the first international emissions ‘cap and trade’ regime in 2005, through which polluting industries must limit their emissions or buy credits from others which have not used their full allowance (see Box 1). The UK participated in the EU ETS until 2021, when it created its own domestic Emissions Trading System.

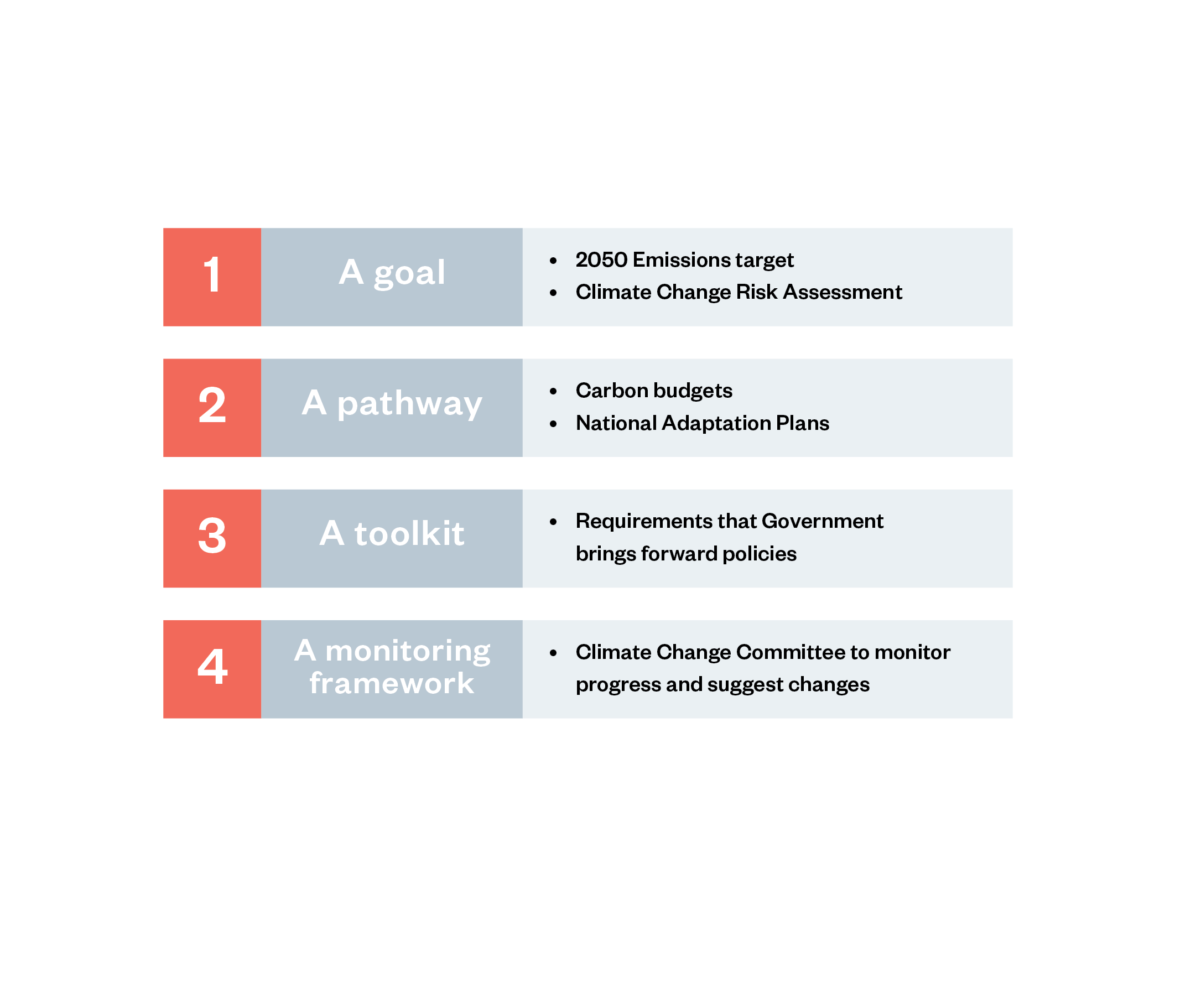

The Climate Change Act is widely acknowledged to be one of the first comprehensive framework laws on climate change and an innovative example of legislation in its whole-economy approach to climate governance.[26] The basic architecture consists of a legally defined national long-term objective, supported by statutory processes and institutions. Since its passage in 2008, several other countries have emulated features of the Act, including France, Germany, Mexico and New Zealand.

Box 1: Carbon credits

A carbon credit is an allowance that represents the avoidance or removal of one tonne of greenhouse gas emissions (measured in CO2e). Countries, businesses, institutions and individuals can buy carbon credits to ‘offset’ their continued emissions, for example by paying a company to plant trees on their behalf. Carbon credits are exchanged in ‘voluntary carbon markets’, which differ from legal emissions trading schemes, in which participants are compelled to compensate for their emissions with a specific number of permits.

Carbon credits are generated by organisations or projects involved in activities which either reduce emissions, for example, by protecting forested land or developing renewable energy or by removing emissions, for example, by planting new trees or through technologies designed to extract greenhouse gases from the atmosphere such as direct air capture. Most carbon credits are issued for emission reductions rather than removals. The project or organisation responsible can measure its impact and sell an equivalent number of carbon credits, generally certified by an independent body.

While both the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement contain provisions for an international carbon marketplace, the practice of carbon offsetting is highly controversial. Environmental NGOs such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth argue that polluters use carbon credits to avoid the more fundamental work of decarbonising their own activities and point out that projects in the Global South have displaced communities from their land and livelihoods.[27] Critics note that the climate impact of offsetting projects can be exaggerated, with many schemes unable to demonstrate that greenhouse gas cuts are additional (would not have happened without the project) or permanent. Recent analysis of the top 50 offset projects suggests that 78% likely did not represent genuine carbon reductions and were therefore ‘worthless’.[28]

The Climate Change Committee says that ‘high-integrity’ carbon credits can play a ‘small but important role’ in the transition to ‘net zero’ but calls for stricter guidance and regulation to ensure businesses do not substitute credits for directly reducing their emissions.[29] The Climate Change Act requires the UK Government to limit its use of carbon credits in meeting its carbon budgets; this limit has been set at 2.8% of the overall carbon budget on the advice of the Climate Change Committee.

Objectives of the Climate Change Act and emissions regulation

As climate change is largely produced by the emission of CO2 and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the Climate Change Act’s high level climate mitigation ambition is to reduce emissions. The Act initially set an economy-wide target date of 2050 for reducing emissions by at least 80% compared to 1990 levels, and by at least 34% by 2022; in 2019, this was amended to net zero by 2050 (see Box 1) to align it with the 2015 Paris Agreement. So far, these targets have only applied to territorial emissions – emissions that occur within the UK’s borders – although, in line with official advice, the UK Government has announced it will legislate to incorporate shipping and aviation emissions into its sixth carbon budget, covering the years 2033–37.

Box 2: Net zero, gross zero and carbon neutrality

In climate policy, net zero refers to the objective of limiting greenhouse gas emissions by balancing the amount that is emitted with the amount mitigated and removed through carbon sinks and negative emissions technologies.

To achieve net zero targets, governments have adopted plans that include initiatives to abate greenhouse gas emissions by, for example, replacing fossil fuel energy sources with renewable ones, removing emissions through carbon capture and storage technologies and nature-based solutions, and offsetting emissions through carbon markets.[30] Usually net zero, is in reference to the 2050 deadline, though some jurisdictions, such as Denmark, have set an earlier deadline to achieve net zero.[31]

While net zero objectives provide for the continuation of some residual emissions that can be removed, the concept of ‘gross zero’ refers to the absolute reduction of emissions from all sources. It is widely agreed among governments that net zero targets are more realistic than gross zero targets.[32] The term ‘net zero’ is often used interchangeably with the term ‘carbon neutrality’, though technically this refers specifically to the reduction of CO2 emissions, rather than greenhouse emissions more widely. The UK Government uses the term net zero to refer to its 2050 emissions reduction targets.

As noted above, the Climate Change Act also established the Climate Change Committee, an independent body set up to advise the UK Government on setting targets and to report on progress. The Act covers the emissions from all devolved nations, although devolved administrations receive specific independent advice from the Climate Change Committee. In addition to the Climate Change Act, in 2009, Scotland also introduced legislation committing to net zero by 2045, and Wales introduced legislation in 2016 to reduce emissions by at least 80% by 2050, subsequently amended to reflect the UK-wide net zero target.[33]

The literature on the Climate Change Act in the UK, and the development of similar legislative instruments in other countries, generally contends that action against climate change requires a legislative framework, as this can help to limit political backsliding and improve policy integration across public sector bodies.[34] The UK Climate Change Act was intended to give a clear, legally binding indication of the long-term direction of travel for the UK Government, business and the public. According to the Climate Change Committee, ‘the notion behind the Act was that while politicians might disagree on how to respond to climate change, they shouldn’t disagree on whether to respond’.[35] This is embodied in the Act’s framework, which sets overarching emissions reduction targets without prescribing how they will be met, giving future governments flexibility in designing climate policy. The advantages and limitations of this approach are discussed below.

Figure 4: The four pillars of the UK Climate Change Act[36]

Mechanisms for implementing carbon emissions regulation

Framework

The Climate Change Act describes several mechanisms for achieving its mitigation and adaptation objectives. Of most relevance here are the statutory long-term emissions target; the statutory five-year carbon budgets; the establishment of an advisory body – the Climate Change Committee; the taking of enabling powers to introduce regulations; and the duty to report on progress.[37]

Section 1(1) of the Act establishes the duty of the Secretary of State to ‘ensure that the net UK carbon account for the year 2050 is at least 80% lower than the 1990 baseline’. The baseline is defined in Section 1(2) as the aggregate amount of net UK emissions of CO2 for 1990 and other greenhouse gases defined in Section 24(1). Under the terms of Section 2 of the Act, the UK became the first major economy to enshrine a net zero target in legislation by 2050.[38]

The 2019 amendment to the Climate Change Act was made based on advice from the Climate Change Committee, and reflected the conclusions of the IPCC in its 2018 Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C that achieving net zero emissions by 2050 is necessary to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C by the end of the century.[39] Parties to the UNFCCC subsequently agreed to include the objective of net zero by 2050 in the Glasgow Climate Pact agreed at COP26 in 2021.[40] As of 2023, at least 70 countries had extended emissions reduction plans to incorporate this objective, and 27 countries had enshrined these commitments in domestic legislation.[41]

To pursue these objectives, Section 4 of the Climate Change Act mandated the UK Government to establish ‘carbon budgets’ for five-year periods, beginning with the period 2008–2012 (see Box 2). They are formally set by the UK Parliament on the advice of the Climate Change Committee. Section 4(2) of the Act mandates the UK Government to legislate carbon budgets 12 years in advance of the start date. This approach was chosen ‘to provide enough time for the Government to develop and enact policies and for businesses to invest’.[42]

Box 3: Carbon budgets, global carbon budgets and sectoral carbon budgets

In the context of the UK Climate Change Act, carbon budgets set the amount of net UK carbon that can be emitted. While the first five carbon budgets only incorporated territorial emissions, the sixth carbon budget will also incorporate shipping and aviation emissions. National carbon budgets have also been adopted into legislation by jurisdictions including the European Union and Japan.[43] Carbon budgets are related to but different from ‘global carbon budgets’, which refer to estimates of the total level of emissions permissible under global climate objectives.[44]

Elsewhere, governments have adopted ‘sectoral carbon budgets’ that set limits on the amount of net CO2 or CO2e emissions for specific sectors of the economy, such as industrial processes and product use, agriculture, and land use, land use change and forestry. Germany has taken this approach, setting annual budgets for six high emitting sectors over the 2020s, although this has been politically controversial and the German government has suggested rescinding these targets. Although policymakers anticipated that the UK Government would also adopt sectoral carbon budgets within the national carbon budgets, this was ultimately not pursued.

Box 4: Measuring UK greenhouse gas emissions: Territorial, residence and footprint estimates, and scopes[45]

Progress towards achieving carbon budgets and the net zero goal is measured through estimates of territorial emissions, which include emissions and greenhouse gas removals from UK-based businesses; the activities of people living in the UK and visiting the UK; and land, including forests and crop or grazing land. From 2023, they also include emissions and removals from international aviation and shipping, but exclude emissions and removals from UK residents and businesses registered abroad; the production of goods and services the UK imports from other countries; burning biomass – wood, straw, biogases and poultry litter – for energy production. This data is collected by the Department for Energy Security & Net Zero (DESNZ).

As part of the UK’s Environmental Accounts, the Office for National Statistics produces emissions estimates data covering emissions by UK residents and UK-registered businesses, regardless of where they are based.

Defra also produces estimates of the UK’s ‘carbon footprint’, which accounts for emissions through the supply chain of goods and services consumed in the UK, wherever they are produced in the world. This allows for emissions from UK imports, but excludes emissions resulting from goods produced in the UK that are exported.

These measures are different but related to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol’s classification of emissions that is used in company reporting. The initiative ‘Greenhouse Gas Protocol’ provides standards, guidance, tools and training for businesses and governments to measure and manage climate-warming emissions. Greenhouse Gas Protocol guidance includes: Scope 1 emissions include those produced from sources that an organisation owns or controls; Scope 2 emissions include those produced indirectly from the generation of purchased energy; Scope 3 emissions are all indirect emissions, not included in Scope 2, that occur in the value chain of the reporting company.[46] At the time of writing, in the UK, large organisations are currently required to disclose Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions in their annual reports as part of the government’s Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting framework.

Responding to the publication of the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) standards for sustainability-related disclosures in 2023, which requires companies to report all scope emissions, the UK government issued a call for evidence to help inform its decision on whether to endorse ISSB standards in the UK.[47]

Part 2 of the Climate Change Act established the Climate Change Committee which, as noted above, was set up in shadow form before the Act was passed, and is a statutory body made up of leading climate scientists and senior civil servants. The Climate Change Committee is responsible for advising the UK and devolved governments on carbon budgets and long-term emissions targets, as well as on emissions from international aviation and international shipping. Section 36 of the Act also mandates the Climate Change Committee to report progress in the realisation of carbon budgets and the 2050 target to the UK Parliament and devolved legislatures each year, and provide analysis of actions taken.

As a non-departmental public body, the budget of the Climate Change Committee is determined by the UK Government.[48] The limited role of the committee reflects a political sensitivity to the potential costs of climate policy, which is controlled by the Treasury.[49] In developing carbon budgets, the committee is required to take into account various contextual circumstances, including competitiveness, fuel poverty, fiscal considerations and energy policy.[50]

Although the Climate Change Act does not otherwise prescribe climate policy or government action to achieve its long-term emissions reduction objectives and climate budgets, Part 3 of the Act establishes a framework for national authorities to develop regulations for the setting up and operation of Emissions Trading Systems.

The legislative framework of the Climate Change Act has ‘served as a model for the development of climate legislation in a number of countries, including Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand and Sweden’. Each of these countries have adopted laws that ‘involve setting interim targets on the pathway to a long-term goal and independent evidence-based advice’.[51] Particularly following the adoption of the Paris Agreement and the requirement to develop Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) plans, however, other governments have incorporated a legislative framework for developing economy-wide strategies for the realisation of objectives, which is not part of the UK Climate Change Act.

Governance structure

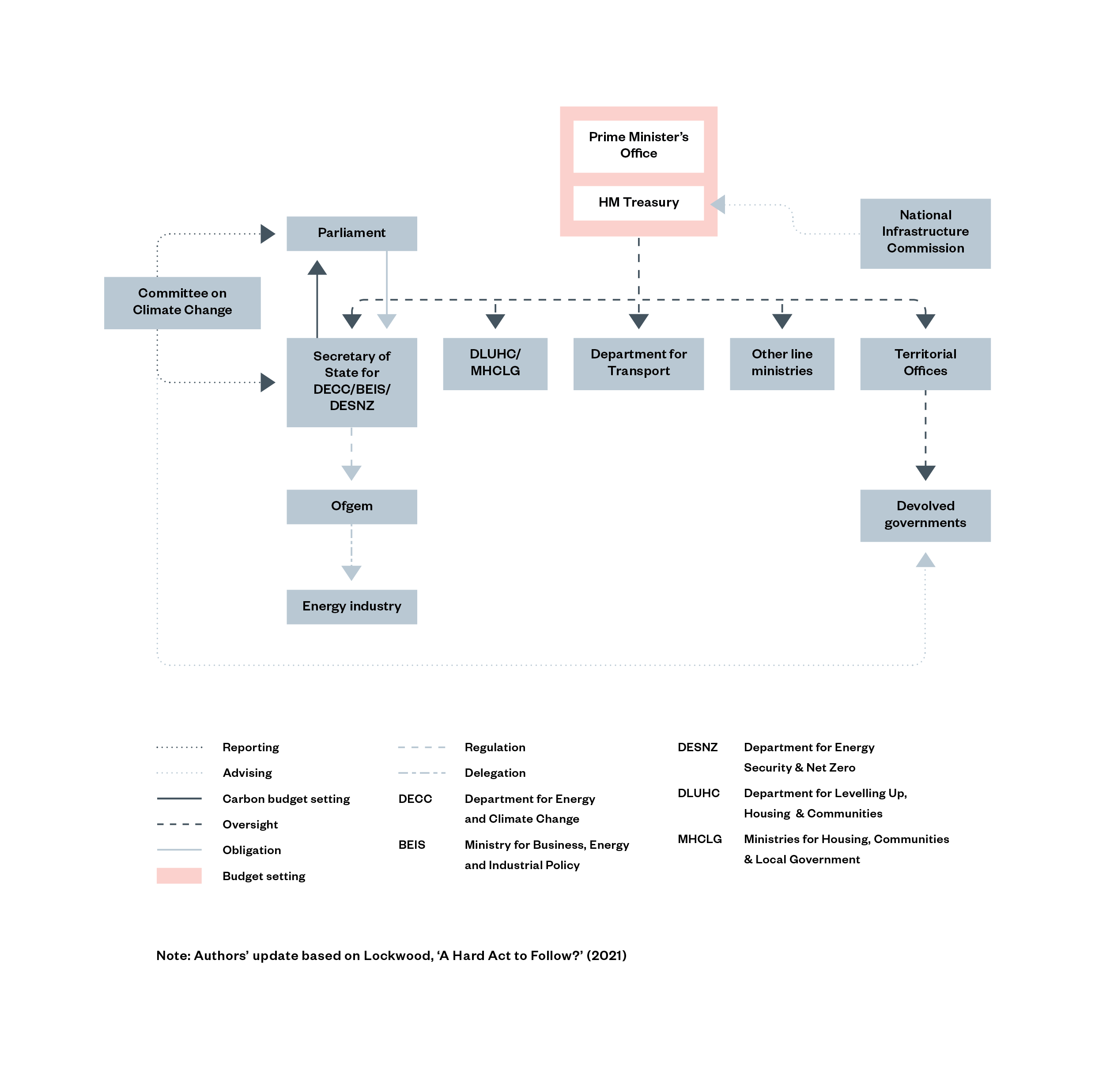

As the Climate Change Act is an economy-wide law, several government departments and other public bodies are involved in the realisation of the Act’s emissions reduction objectives. The enactment of the Act was followed by the establishment of some new organisations and the reconfiguration of others to incorporate responsibility for emissions reduction policies within sectors. In general, ‘the new CCA targets and arrangements were layered on top’[52] of existing institutions. An overview of the governance structure for emissions reduction as of 2024 is included in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Structure of UK emissions reduction governance, 2024[53]

Although not mandated in the Climate Change Act, in October 2008, the UK Government established the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) with overall responsibility for energy and climate change policy. The DECC consolidated functions previously within the mandate of the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). However, Defra continued to be responsible for the climate adaptation objectives of the Act.[54] Lockwood notes that ‘previously, the lack of ownership of climate change targets in the Departments required to actually deliver them (i.e. Business and Transport), had been a real problem’.[55]

In 2016, DECC was dissolved following a period of budget cuts within the UK Government’s broader programme of fiscal austerity, and responsibility for the mitigation objectives of the CCA was moved to the new Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). This was met at the time with significant criticism from opposition politicians, as well as climate and environmental groups, who perceived the restructuring decision as a de-prioritisation of climate ambition,[56] though others were more sanguine, suggesting the decision would advance green innovation and growth.[57] Following the global energy crisis triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in 2023 climate mitigation policy became the responsibility of a new department, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ). Interviewees for this project broadly agreed that these departmental changes had not undermined the general strategic direction provided by the Climate Change Act.

Although there were concerns that DECC would struggle to oblige other departments to deliver economy-wide targets,[58] interviewees for this project, and in wider academic research generally, agree that centralising responsibility for climate targets within DECC and its successors has improved policy coordination and integration by providing clarity on the strategic direction of the UK Government.[59] Nonetheless, there is still concern about coordination between climate change policy and regulation of energy markets, which is the responsibility of the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem).[60]

Reflecting its broader position within the UK Government administration, the Treasury has remained influential in the governance of the Climate Change Act through its budgetary oversight authority and veto position in government spending decisions.[61] This role is not formalised within the Act, but rather has emerged through the ‘instigation of specific climate and energy policies, such as major reform of support for low carbon electricity generation and the introduction of the Carbon Price Floor’,[62] – a type of taxes on fossil fuels – and in conflicts over the feasibility of carbon budget targets.[63] Interviewees for this project described the Treasury as being generally intransigent with regards to emissions reduction policy, pointing to the need to ensure integration of objectives within the Treasury in UK governance.

The Climate Change Act has been accompanied by some legislated policies to reduce emissions, including Energy Acts in 2008 and 2023, which made provision for greater renewable energy generation, and the Zero Emissions Vehicle mandate, which sets the pathway for an electric vehicle transition and became law in 2024. However, the UK Government has also relied on non-statutory policies and strategies, targeting both economy-wide objectives, as well as emissions reductions within sectors. These include, most recently the 2021 Net Zero Strategy (Build Back Greener), subsequently updated in 2022 and 2023.[64]

Reflecting wider findings in academic literature, interviewees for this project held varying perceptions about the reliance on non-statutory instruments, with some contending that the absence of policy mandates enables the UK Government to adapt implementation approaches in response to changing scientific knowledge, market dynamics, and electoral politics.[65] Others, however, felt that the absence of sufficient statutory implementation frameworks had resulted in a lack of certainty on the process for realising emissions reduction objectives, as they were not protected from changes in political priorities.

Monitoring, evaluation and accountability

The Climate Change Act established legally binding mechanisms for reporting and monitoring of progress in setting and meeting carbon budgets and the long-term objectives, notably through the requirement for regular reporting to Parliament and Climate Change Committee annual progress reports.[66] Nonetheless, as with climate change legislation in general, the UK Act encounters a challenge of formal accountability as there is no sanction if the Government does not achieve the mandated objectives.[67]

In establishing a ‘legal duty to act’, the Act created an avenue for citizens to pursue legal action against the UK Government if it can be deemed to be in breach of the Act. In July 2022, Friends of the Earth, ClientEarth, environmental campaigner Joanna Wheatley and Good Law Project successfully pursued legal action in the High Court against the UK Government on the basis that its plans for realising the carbon emissions objectives enshrined in the CCA did not meet the ‘minimum legal standards’. In response, the UK Government published a revised Net Zero strategy in March 2023.

In February 2024, Friends of the Earth, ClientEarth and the Good Law Project pursued further legal action on the basis that this revised strategy ‘lacks critical information on the very real risks that its policies will fail to deliver the cuts needed to meet legally binding carbon reduction targets and relies too heavily on unproven technologies’.[68] The Scottish Government recently dropped its statutory commitment to reduce emissions by 75% by 2030, enshrined in its Emissions Reduction Act 2019 (it is still subject to targets under the Climate Change Act). It is likely that a judicial review will follow this decision, but it raises questions about the efficacy of legally mandated targets as emissions get harder to achieve. One interviewee for this project explained that the UK Government take the possibility of judicial review into account when making decisions.

At the same time, it was suggested by interviewees during the roundtable discussion that there remains a lack of clarity around what constitutes a breach of the legal duty to act. Uncertainty around this increases the legal costs for both government bodies and those pursuing legal action. Elsewhere, climate legislation includes provisions to ‘clarify questions of standing or jurisdiction to review decisions and action taken under them’. For example, Section 23 of Kenya’s Climate Change Act ‘contains provisions that give any citizen the right to bring a complaint before the Land and Environment court against any person acting in a way that may adversely affect adaptation and mitigation activities’.[69]

The establishment of the Climate Change Committee within the Climate Change Act is generally viewed as having strengthened non-binding forms of accountability. As a body made up overwhelmingly of senior and highly credentialed academic climate scientists and researchers, the committee is highly trusted among civil servants and industry stakeholders.[70] Appointments to the committee are made jointly by ministers in the UK and devolved administrations, and are made on the basis of assessments of expertise and disclosure of conflicts of interest.

The information and analysis produced by the committee is widely cited by parliamentarians across the political spectrum in political debates, as well as environmental NGOs in campaigns – including ClientEarth and the Good Law Project in their High Court actions.[71] Academic analysis of the UK experience with the Climate Change Act suggests that ‘an expert advisory body can strengthen climate governance by serving as an impartial knowledge broker, contributing to more evidence-based and ambitious policymaking’.[72]

At the same time, one interviewee for this project suggested that the constitution of the Climate Change Committee as a largely ‘technocratic’ and ‘depoliticised’ body made up of scientific experts also creates risks of political backlash – ‘…people [could] say: “we are now being governed by someone without electoral authority”’. In general, interviewees agreed that these risks could be mitigated through increasing channels for citizen and democratic participation when developing policies to implement the Act.

Public impact of carbon emissions regulation

The Climate Change Act’s impact on emissions

Although the UK’s current emissions make up about 1% of the global total, it is responsible for 3% of cumulative emissions since 1850[73] and over 5% if responsibility for territories under colonial rule are included, making it the fourth largest contributor historically.[74] The UK is a signatory of the Paris Agreement which adheres to the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’, reflecting that developed countries are in a stronger position than developing countries to urgently reduce their emissions. Successive UK governments have also sought a position of climate leadership on the world stage, pointing to the targets enshrined in the Climate Change Act as the first of their kind, and interviewees for this study emphasised that demonstrating moral leadership was a key component of the Act.

The Climate Change Act is the main available mechanism to end the UK’s contribution to climate change, but attribution of emissions reductions is not straightforward. According to the Climate Change Committee, ‘the existence of the Act is widely credited with having been an important contributing factor to the continued reductions in the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions’.[75] The UK has reduced its territorial emissions by 49% since 1990 and its consumption emissions – a broader measure that includes aviation and shipping and the consumption of imported goods to the UK – by 36%.[76] The bulk of decarbonisation has occurred in the power sector, driven by the transition from coal to gas starting in the late 1970s and accelerating in the 1990s, with another wave in the 2010s.[77]

There has also been a long-term reduction in industrial emissions due to improvements in energy efficiency and to structural changes in the UK economy, which has seen a decline in manufacturing and a rise in services. These changes were largely not a result of deliberate climate policy, and emissions were clearly on a downward trajectory before the Climate Change Act was passed. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the Act was layered on top of the UK’s participation in existing regulatory regimes related to emissions, notably through the EU, which contributed an estimated 40% of the reduction in UK emissions between 1990 and 2016.[78]

Nonetheless, the Climate Change Act, and particularly the activities of the Climate Change Committee, inspired and legitimised a flurry of climate policy, including support for renewable energy, which have accompanied further emissions reductions. Policies enacted recently, most importantly the phasing in of electric vehicles, will have a significant impact when implemented. However, initial progress has slowed, and the last decade has seen several policy reversals, including cutting renewable energy subsidies, privatising and later de-greening the Green Investment Bank, and reducing corporation tax for oil and gas sectors. The UK Government has generally emphasised market forces and voluntary behaviour change in emissions reduction initiatives, as demonstrated in the 2017 Clean Growth Strategy, which neglected major sources of emissions like aviation, livestock and electricity generation.[79]

The UK comfortably met its first three carbon budgets, with one interviewee for this study, who was involved in designing the Climate Change Act, suggesting that, in hindsight, these were ‘basically pointless as they were set at such a low level of ambition’. The Climate Change Committee has warned that the UK Government is not on track to meet its future commitments, responding to its 2023 delivery plan with ‘markedly’ less confidence that the UK would meet its targets and assessing that there were ‘credible’ policies for just one-fifth of the emissions cuts needed over the next decade.[80] The report highlighted a lack of urgency, and pointed out that planned airport expansion and new licences for North Sea oil and gas exploration were incompatible with decarbonisation targets. This points to what one interviewee described as the Climate Change Act’s greatest weakness: the lack of a comprehensive approach that covers both upstream sources of emissions, notably the extraction of fossil fuels, and downstream sources at the point of use. As Averchenkova et al found in expert interviews, it is not clear, due to its limited accountability mechanism, that ‘the Act offers sufficient protection to force through the emission cuts of the future’.[81]

The benefits of reducing emissions

Reducing emissions to mitigate the worst effects of climate and ecological breakdown is in the public interest at both a global and national scale. As climate change leads to more severe and less predictable weather events, the UK is exposed to coastal change and floods, as seen during the winters of 2020–21 and 2021–22, and to higher summer temperatures, with greater risk of heatwaves, drought and wildfires. The direct effects of these events, as well as the impact on air quality, food and water availability, and increased risks of infectious and vector-borne diseases, make climate change a ‘dual threat to lives and livelihoods in the UK’.[82] Interviewees also noted the role of climate leadership in inspiring international action and in lowering costs of solutions that can then be adopted elsewhere.

In 2019, the Climate Change Committee established the Advisory Group on Costs and Benefits of Net Zero, whose initial report noted the substantial co-benefits of decarbonisation, particularly in relation to health.[83] The Climate Change Committee’s statutory progress reports to Parliament consider the co-benefits of the UK Government’s decarbonisation pathways: it has noted that current approach of relying heavily on technology to reach its targets ‘misses the opportunity to maximise on co-benefits to the transition via improvements to health through more comfortable homes, reduced air pollution, healthier diets and more active lifestyles”.[84] In its 2023 ‘Progress in reducing emissions’ report, the Climate Change Committee set out possible alternatives to government plans and their co-benefits.[85] Figure 6 lists the key co-benefits of mitigating climate change by reducing emissions.

Figure 6: Co-benefits of reducing emissions

| Health |

|

| Housing and fuel poverty |

|

| Jobs | |

| Energy security |

|

The Climate Change Act’s impact on public debate

The Climate Change Act was implemented during a period of heightened public concern about climate change, driven by a coordinated campaign by an established coalition of environmental NGOs and accompanied briefly by a UK Government public awareness campaign (this was facilitated by the Central Office for Information, which was closed down in 2012, and described as ‘a huge loss’ by one interviewee in this study). The intervening years have seen increased political and economic turbulence, and public opinion has accordingly fluctuated relative to other issues, including the economy, the NHS, membership of the European Union and immigration.[94] However, polling consistently finds climate change to be a major public concern, featuring in the top five most important facing Britain in the Ipsos MORI issues tracker every year since 2020.[95] This may reflect the consensus underpinning the Climate Change Act, which Averchenkova et al found ‘had facilitated a more predictable and fact-based political debate’, through its provision of timelines and statutory advice from the Climate Change Committee, which itself has served to legitimise climate action and to inform a public debate.[96]

However, though not as polarised as in some other countries, climate change has become an increasingly partisan issue, notably as a result of pressure from groups within and external to the Conservative Party.[97] In 2018, Fankhauser et al concluded that the Climate Change Act had largely been a success in improving political debate, but recommended that ‘a strong, proactive focus on engaging the general public on climate policy would help to strengthen the societal consensus on climate action’.[98] Experts interviewed for this project generally agreed on the Act’s resilience, but noted that public engagement was increasingly important as further reductions will depend significantly on measures that will have a greater impact on everyday life , for which public support is necessary.[99]

Although there is broad support for climate action, there is much less understanding of the specific policies required to drastically reduce emissions. Roundtable participants emphasised the importance of a ‘broader, participatory, deliberative democracy conversation… around climate change’ to improve public understanding of the challenges and the mechanisms in place to address them. The Climate Change Committee’s 2023 progress report noted that ‘a coherent public engagement strategy on climate action is long overdue’.[100] This suggests that public engagement should perhaps have been a stated objective of the Climate Change Act.

Impact of carbon emissions regulation on market activity and innovation

Section 10(2) of the Climate Change Act describes that ‘economic circumstances, and in particular the likely impact of the decision on the economy and the competitiveness of particular sectors of the economy’ must be considered in both the UK Government’s setting of carbon budgets, and in the Climate Change Committee’s advice in relation to these decisions. Correspondingly, reports presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State must ‘explain how the proposals and policies set out in the report affect different sectors of the economy’ (Section 14(3)). Part 3 of the Act creates broad enabling powers that governments can use to introduce regulations for (a) ‘limiting or encouraging the limitation of activities that consist of the emission of greenhouse gas or that cause or contribute, directly or indirectly, to such emissions’ and (b) ‘encouraging activities that consist of, or that cause or contribute, directly or indirectly, to reductions in greenhouse gas emissions or the removal of greenhouse gas from the atmosphere’.

Beyond these references to economic considerations, the Climate Change Act does not directly address energy markets, innovation and growth. Nonetheless, interviews conducted for this project, as well as existing academic research, point to some potential effects on market activity and innovation. Interviewees overwhelmingly agreed that the Act had effectively delivered a degree of policy certainty by setting long-term emissions targets, indicating to businesses that they should invest in the technologies, practices and skills needed for decarbonisation.

Several interviewees cited the announced ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars, which stimulated a move by the UK automotive sector towards producing electric vehicles. However, the smoothness of this transition has arguably been undermined by somewhat inconsistent messaging and an insufficient investment environment. When the Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced in September 2023 that the ban would be delayed from 2030 to 2035, the automotive industry responded with frustration. The German firm, Volkswagen, stated: ‘We urgently need a clear and reliable regulatory framework which creates market certainty and consumer confidence’,[101] while Ford said the move undermined the ‘ambition, commitment and consistency’ they needed from the UK Government.[102]

Other parts of the private sector have also consistently demanded greater clarity and government investment: for example, in 2022, investors managing £3 trillion in assets called on the UK Government to ‘unleash’ private sector investment and growth by ‘providing certainty and consistency in policy, and strategic public investment in the most critical sectors for decarbonisation’.[103] Interviewees for this study identified that although the Climate Change Act had set a direction of travel, the precise shape of the trajectory towards the net zero target remained unclear. Some interviewees noted that there is broad consensus that the Climate Change Committee’s advice for sectoral decarbonisation should be followed, but conceded that this is not currently happening sufficiently. The UK Government’s limited financial support for decarbonising heating by incentivising the adoption of heat pumps was repeatedly cited as an area in which the Climate Change Committee advice was clear, but in which businesses do not have the confidence to invest sufficiently in the workforce, while incumbent industries have lobbied hard for the continued use of gas.

One area which has seen significant innovation following the Climate Change Act is offshore wind (Interview 1 and 2): the UK is now the world’s second largest offshore wind market after China. The sector benefited from particularly concerted attention between 2010 and 2016, including new legislative forms of price support, clear planning process deadlines, competitive transmission licences and the advent of the Green Investment Bank.[104]

However, as one interviewee noted, the sector’s growth has not led to significant job growth or manufacturing capacity in the UK as most of the equipment is produced elsewhere. One of the interviewees for this study suggested that the lack of supply chain investment was largely due to the relatively small size of the UK market and high costs of doing business; another noted that UK Government has tended to be more proactive in innovating at the first stage of technologies, for example by funding micro-testing, but there is much less support for scaling and implementation stages. While one interviewee highlighted innovation in adapting the electricity grid to renewable energy and in transport, overall the Climate Change Act fell short of fostering ‘the right investment climate’, insofar as ‘we didn’t really direct revenue in a de-risking way for industrial [sectors] to investigate’. The same interviewee, however, noted that industrial actors themselves were slow to advocate for such policies and sought to water down regulations.

Although interviewees acknowledged the limitations of growth and innovation under the Climate Change Act, they generally attributed these to policy failures and ‘forms of regulatory capture’ – related to both information asymmetries between government and market actors, and the structural power of firms – rather than to flaws in the Act itself. They overwhelmingly cited the advantages of a framework act which sets the overall target but gives each democratically elected government flexibility over how to meet that target. Considering how the Act might have been strengthened, they broadly agreed that moves to make the Climate Change Committee’s advice statutory, for example, would have been politically unfeasible and democratically undesirable. However, it was noted that democratic governance of climate mitigation would be strengthened by fostering greater popular understanding and support for necessary policies through much improved public engagement.

Appendix: Anonymised list of interviews

| No. | Role (most relevant) | Date of interview |

| 1 | Member of the House of Lords | 13 March 2023 |

| 2 | Professor, Government advisor | 15 March 2023 |

| 3 | NGO analyst | 15 March 2023 |

| 4 | Academic researcher | 15 March 2023 |

| 5 | Trade union official | 18 March 2023 |

| 6 | Professor, Government advisor | 19 March 2023 |

| 7 | Industry body | 21 March 2023 |

| 8 | DESNZ | 21 March 2023 |

Footnotes

[1] Emissions from gases which hold global warming potential, including methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFC), perfluorocarbons (PFC), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3), are calculated using carbon dioxide equivalent units CO2e.

[2] IPCC, ‘Summary for Policymakers’, 5.

[4] ‘What Is the Difference between Adaptation and Mitigation?’ (30 October 2023) <https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/about/contact-us/faqs/what-is-the-difference-between-adaptation-and-mitigation> accessed 5 May 2024

[5] Office for National Statistics (ONS), ‘The Decoupling of Economic Growth from Carbon Emissions: UK Evidence’; Ritchie and Roser, ‘Who Has Contributed Most to Global CO2 Emissions?’; Malm, Fossil Capital.

[6] ONS, ‘The Decoupling of Economic Growth from Carbon Emissions: UK Evidence’.

[7] ONS, ‘2022 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Final Figures’, 7.

[8] House of Commons Library, UK global emissions and temperature trends (2021) https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/uk-and-global-emissions-and-temperature-trends/

[9] ONS, ‘The Decoupling of Economic Growth from Carbon Emissions: UK Evidence’; ‘2022 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Final Figures’.

[10] ‘Final UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions National Statistics: 1990 to 2022’ (GOV.UK, 27 June 2024) <https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/final-uk-greenhouse-gas-emissions-national-statistics-1990-to-2022> accessed 9 October 2024

[11] J. Kreienkamp, The Long Road to Paris: The History of the Global Climate Change

Regime. Global Governance Institute Policy Brief Series. London: University College London (2019).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Stallworthy, Mark. “Legislating against Climate Change: A UK Perspective on a Sisyphean Challenge.” The Modern Law Review 72, no. 3 (2009): 412–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20533257.

[15] Maslin MA, Lang J and Harvey F, ‘A short history of the successes and failures of the international climate change negotiations’ (2023) 5 UCL Open Environment <https://journals.uclpress.co.uk/ucloe/article/id/904/> accessed 9 October 2024

[16] Institute for Government, The Climate Change Act (2008)

[17] Matthew Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow? The evolution and performance of UK climate governance. Environmental Politics’ (2021).

[18] Institute for Government, The Climate Change Act (2008)

[19] https://www.climateaction.org/news/tony_blair_speaks_at_gleneagles_dialogue_on_climate_change

[20] N. Stern, ‘Economic Impacts of Climate Change’, Cabinet Office (2006).

[21] Institute for Government, The Climate Change Act (2008)

[22] Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, Royal Commission Calls for Transformation in the UK’s Use of Energy to Counter Climate Change, 16 June 2000. https://web.archive.org/web/20070103000009/http://www.rcep.org.uk/news/00-2.htm

[23] BBC, ‘Binding climate targets proposed’, 13 March 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/6444145.stm

[24] N. Carter, ‘The Politics of Climate Change in the UK’ (2014).

[25] Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’ (2018).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Friends of the Earth, ‘A dangerous distraction – the offsetting con’ (2021), https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/insight/dangerous-distraction-offsetting-con.

[28] Nina Lakhani, ‘Revealed: top carbon offset projects may not cut planet-heating emissions, The Guardian, 19 September 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/sep/19/do-carbon-credit-reduce-emissions-greenhouse-gases.

[29] CCC, Voluntary Carbon Markets and Offsetting (2022), https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/voluntary-carbon-markets-and-offsetting/.

[30] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’.

[32] Grantham Research Institute, ‘What Is Net Zero?’ (2019)

[33] Climate Change Committee, Insights Briefing 1: The UK Climate Change Act (2020) https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/CCC-Insights-Briefing-1-The-UK-Climate-Change-Act.pdf

[34] Alina Averchenkova, Sam Fankhauser, and Michal Nachmany, Trends in Climate Change Legislation (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017); Sarah Louise Nash and Reinhard Steurer, ‘Taking Stock of Climate Change Acts in Europe: Living Policy Processes or Symbolic Gestures?’, Climate Policy 19, no. 8 (14 September 2019): 1052–65, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1623164.

[35] Climate Change Committee, Insights Briefing 1.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’; HM Government, Climate Change Act 2008.

[38] Grantham Research Institute, ‘Why Is Net Zero so Important in the Fight against Climate Change?’ (2023).

[39] Grantham Research Institute, ‘Why Is Net Zero so Important in the Fight against Climate Change?’; IPCC, ‘Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty’.

[40] Grantham Research Institute, ‘Why Is Net Zero so Important in the Fight against Climate Change?’

[41] Grantham Research Institute, ‘Evolving Regulation of Companies in Climate Change Framework Laws’ (2023); United Nations, ‘Net Zero Coalition’.

[42] Climate Change Committee, Insights Briefing 1.

[43] Matthews et al., ‘Opportunities and Challenges in Using Remaining Carbon Budgets to Guide Climate Policy’, (2020).

[44] Fankhauser, ‘What Are Britain’s Carbon Budgets?’ (2020)

[45]UK Government, ‘Measuring UK greenhouse gas emissions’ (2024), https://climate-change.data.gov.uk/articles/measuring-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[46] UK Government, ‘UK greenhouse gas emissions reporting: Scope 3 emissions’ (2023), https://www.gov.uk/government/calls-for-evidence/uk-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reporting-scope-3-emissions

[47] UK Government, ‘UK greenhouse gas emissions reporting: Scope 3 emissions’ (2023), https://www.gov.uk/government/calls-for-evidence/uk-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reporting-scope-3-emissions

[48] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’.

[49] Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[50] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’.

[51] OECD, ‘The United Kingdom’s pioneering Climate Change Act’ (2022), https://www.oecd.org/climate-action/ipac/practices/the-united-kingdom-s-pioneering-climate-change-act-c08c3d7a/

[52] Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[53] Authors’ update based on: Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[54] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’.

[55] Lockwood, ‘The Political Sustainability of Climate Policy’.

[56] Vaughan, ‘Abolition of Decc “Major Setback for UK’s Climate Change Efforts”’, The Guardian, (2016).

[57] Fankhauser, ‘Why the End of the Department for Energy and Climate Change Could Be Good News on Climate Change’, (2016).

[58] A. Stratton, ‘Debutant Miliband Brings Clout to New Department’, The Guardian, (2008); Lockwood, ‘The Political Sustainability of Climate Policy’ (2013).

[59] Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[60] Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’; Interview with Jim Watson.

[61] Craig, ‘“Treasury Control” and the British Environmental State’ (2018); Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[62] Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[63] Lockwood, ‘The Political Sustainability of Climate Policy’; Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’.

[64] Alan Walker and Dominic Carver, ‘Government Policy on Reaching Net Zero by 2050’, 22 February 2024, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2023-0124/.

[65] Alina Averchenkova, Sam Fankhauser & Jared J. Finnegan (2021) The impact of strategic climate legislation: evidence from expert interviews on the UK Climate Change Act, Climate Policy, 21:2, 251-263, DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2020.1819190

[66] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’; HM Government, Climate Change Act 2008.

[67] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 Years of the UK Climate Change Act’.

[68] Damien Gayle, ‘UK Ministers in Court Again over Net Zero Plans’, The Guardian, 20 February 2024, sec. Environment, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/feb/20/uk-ministers-in-court-again-over-net-zero-plans.

[69] Katherine Higham, Alina Averchenkova, Joana Setzer and Arnaud Koehl, ‘Accountability mechanisms in climate change framework laws’, 2021, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Accountability-mechanisms-in-climate-change-framework-laws.pdf, p. 21

[70] Averchenkova et al., ‘The Impact of Strategic Climate Legislation’.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Carbon Brief, ‘Which countries are historically responsible for climate change?’ (2021) https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-which-countries-are-historically-responsible-for-climate-change/

[74] Carbon Brief, ‘How colonial rule radically shifts responsibility for climate change’ (2023) https://www.carbonbrief.org/revealed-how-colonial-rule-radically-shifts-historical-responsibility-for-climate-change/

[75] CCC, Insights Briefing 1

[76] ONS, ‘Measuring UK greenhouse gas emissions’ (2023) https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/methodologies/measuringukgreenhousegasemissions

[77] Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[78] CCC cited in Lockwood, ‘A Hard Act to Follow?’

[79] Peter Somerville, ‘The continuing failure of UK climate change mitigation policy’ (2021). Critical Social Policy, 41(4), 628-650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018320961762

[80] CCC, 2023 Progress Report to Parliament, https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/2023-progress-report-to-parliament/.

[81] Averchenkova et al, The impact of strategic climate legislation

[82] UK Health Security Agency, ‘11 things to know about the Health Effects of Climate Change Report’, 11 December 2023, https://ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2023/12/11/11-things-to-know-about-the-health-effects-of-climate-change-report/

[83] Paul Ekins, ‘Report to the Committee on Climate Change of the Advisory Group on Costs and Benefits of Net Zero (2019). https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Advisory-Group-on-Costs-and-Benefits-of-Net-Zero.pdf

[84] CCC, ‘Progress in reducing emissions: 2022 Report to Parliament’ (2022). https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/2022-progress-report-to-parliament/

[85] CCC, ‘Progress in reducing emissions: 2023 Report to Parliament’ (2023). https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/2023-progress-report-to-parliament/

[86] Office of Health Improvement and Disparities, ‘Climate and health: Applying All Our Health’ (2022) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/climate-change-applying-all-our-health/climate-and-health-applying-all-our-health

[87] Ibid.

[88] The Health Foundation, ‘Health benefits of active travel: preventable deaths’ (2021). https://www.health.org.uk/evidence-hub/transport/active-travel/health-benefits-of-active-travel-preventable-early-deaths

[89] Grantham Institute Briefing Paper no.31, ‘Co-benefits of climate change mitigation in the UK:

What issues are the UK public concerned about and

how can action on climate change help to address them?’ (2019) https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/grantham-institute/public/publications/briefing-papers/Co-benefits-of-climate-change-mitigation-in-the-UK.pdf

[90] Office of Health Improvement and Disparities, Climate and health

[91] Ibid.

[92] ONS, ‘Experimental estimates of green jobs’ (2024) https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/bulletins/experimentalestimatesofgreenjobsuk/2024

[93] TUC, ‘Ranking G7 Green Recovery Plans and Jobs’ (2021) https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-05/TUC%20G7%20Green%20Recovery%20Ranking%20report.pdf

[94] Grantham Institute Briefing Paper No 31

[95] Ipsos Issues Index (2020, 2021, 2022, 2023) https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/ipsos-issues-index

[96] Averchenkova et al, ‘The impact of strategic climate legislation’

[97] Notably, the Net Zero Scrutiny Group of backbench Conservative MPs and Reform UK.

[98] Grantham Research Institute, ‘10 years of the Climate Change Act’.

[99] CCC, ‘The Sixth Carbon Budget: the UK’s Path to Net Zero’ (2020) https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/The-Sixth-Carbon-Budget-The-UKs-path-to-Net-Zero.pdf#page=5

[100] CCC, 2023 Progress Report

[101] Reuters, ‘Auto industry slams Britain’s petrol car ban delay and confusion’, 20 September 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/british-carmakers-slam-flip-flop-petrol-car-ban-seek-certainty-2023-09-20/

[102] Ford statement on 2030, 20 September 2023, https://media.ford.com/content/fordmedia/feu/gb/en/news/2023/09/20/ford-statement-on-2030.html

[103] E3G, ‘Investors managing £3 trillion in assets call on UK government to deliver Net Zero Investment Plan’ 2022. https://www.e3g.org/news/investors-managing-3-trillion-in-assets-call-on-uk-government-to-deliver-net-zero-investment-plan/

[104] Institute for Government, ‘The development of the UK’s offshore wind sector 2010–16’, 2023. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-10/Case-study-offshore-wind-2010-2016.pdf

Image credit: LeoPatrizi

Related content

New rules?

Lessons for AI regulation from the governance of other high-tech sectors