Rethinking data and rebalancing digital power

What is a more ambitious vision for data use and regulation that can deliver a positive shift in the digital ecosystem towards people and society?

17 November 2022

Reading time: 186 minutes

Letter from the working group co-chairs

This project by an international and interdisciplinary working group of experts from academia, policy, law, technology and civil society, invited by the Ada Lovelace Institute, had a big ambition: to imagine rules and institutions that can shift power over data and make it benefit people and society.

We began this work in 2020, only a few months into the pandemic, at a time when public discourse was immersed in discussions about how technologies – like contact tracing apps – could be harnessed to help address this urgent and unprecedented global health crisis.

The potential power of data to affect positive change – to underpin public health policy, to support isolation, to assess infection risk – was perhaps more immediate than at any other time in our lives. At the same time, concerns such as data injustice and privacy remained.

It was in this climate that our working group sought to explore the relationship people have with data and technology, and to look towards a positive future that would centre governance, regulation and use of data on the needs of people and society, and contest the increasingly entrenched systems of digital power.

The working group discussions centred on questions about power over both data infrastructures, and over data itself. Where does power reside in the digital ecosystem, and what are the sources of this power? What are the most promising approaches and interventions that might distribute power more widely, and what might that rebalancing accomplish?

The group considered interventions ranging from developing public-service infrastructure to alternative business models, from fiduciary duties for data infrastructures to a new regime for data under a public-interest approach. Many were conceptually interesting but required more detailed thought to be put into practice.

Through a process of analysis and distillation, that broad landscape narrowed to four areas for change: infrastructure, governance, institutions and democratic participation in decisions over data processing, collection and use. We are happy that the group has endorsed a pathway towards transformation, identifying a shared vision and practical interventions to begin the work of changing the digital ecosystem.

Throughout this process, we wanted to free ourselves from the constraints of currently perceived models and norms, and go beyond existing debates around data policy. We did this intentionally, to extend the scope of what is politically thought to be possible, and to create space for big ideas to flourish and be discussed.

We see this work as part of one of the most challenging efforts we have to make as humans and as societies. Its ambitious aim is to bring to the table a richer set of possibilities of our digital future. We uphold that we need new imaginaries if we are to create a world where digital power is distributed among many and serves the public good, as defined in democracies.

We hope this report will serve as both a provocation and a way to generate constructive criticism and mature ideas on how to transform digital ecosystems, but also a call to action for those of you – our readers – who hold the power to make the interventions we describe into political and business realities.

Diane Coyle

Bennett Professor of Public Policy, University of Cambridge

Paul Nemitz

Principal Adviser on Justice Policy, European Commission and visiting Professor of Law at College of Europe

Co-chairs

Rethinking data working group

A call for a new vision

In 2020, the Ada Lovelace Institute characterised the digital ecosystem as:

- Exploitative: Data practices are exploitative, and they fail to produce the potential social value of data, protect individual rights and serve communities.

- Shortsighted: Political and administrative institutions have struggled to govern data in a way that enables effective enforcement and acknowledges its central role in the data-driven systems.

- Disempowering: Individuals lack agency over how their data is generated and used, and there are stark power imbalances between people, corporations and states.1

We recognised an urgent need for a comprehensive and transformative vision for data that can serve as a ‘North Star’, directing our efforts and encouraging us to think bigger and move further.

Our work to ‘rethink data’ began with a forward-looking question:

‘What is a more ambitious vision for data use and regulation that can deliver a positive shift in the digital ecosystem towards people and society?’

This drove the establishment of an expert working group, bringing together leading thinkers in privacy and data protection, public policy, law and economics from the technology sector, policy, academia and civil society across the UK, Europe, USA, Canada and Hong Kong.

This disciplinarily diverse group brought their perspectives and expertise to understand the current data ecosystem and make sense of the complexity that characterises data governance in the UK, across Europe and internationally. Their reflection on the challenges informed a holistic approach to the changes needed, which is highly relevant to the jurisdictions mentioned above, and which we hope will be of foundational interest to related work in other territories.

Understanding that shortsightedness limits creative thinking, we deliberately set the field of vision to the medium term, 2030 and beyond. We intended to escape the ‘policy weeds’ of unfolding developments in data and technology policy in the UK, EU or USA, and set our sights on the next generation of institutions, governance, infrastructure and regulations.

Using discussions, debates, commissioned pieces, futures-thinking workshops, speculative scenario building and horizon scanning, we have distilled a multitude of ideas, propositions and models. (For full details about our methodology, see ‘Final notes’.)

These processes and methods moved the scope of enquiry on from the original premise – to articulate a positive ambition for the use and regulation of data that recognised asymmetries of power and enabled social value – to seeking the most promising interventions that address the significant power imbalances that exist between large private platforms, and groups of people and individuals.

This report highlights and contextualises four cross-cutting interventions with a strong potential to reshape the digital ecosystem:

- Transforming infrastructure into open and interoperable ecosystems.

- Reclaiming control of data from dominant companies.

- Rebalancing the centres of power with new (non-commercial) institutions.

- Ensuring public participation as an essential component of technology policymaking.

The interventions are multidisciplinary and they integrate legal, technological, market and governance solutions. They offer a path towards addressing present digital challenges and the possibility for a new, healthy digital ecosystem to emerge.

What do we mean by a healthy digital ecosystem? One that privileges people over profit, communities over corporations, society over shareholders. And, most importantly, one where power is not held by a few large corporations, but is distributed among different and diverse models, alongside people who are represented in, and affected by the data used by those new models.

The digital ecosystem we propose is balanced, accountable and sustainable, and imagines new types of infrastructure, new institutions and new governance models that can make data work for people and society.

Some of these interventions can be located within (or built from) emerging or recently adopted policy initiatives, while others require the wholesale overhaul of regulatory regimes and markets. They are designed to spark ideas that political thinkers, forward-looking policymakers, researchers, civil society organisations, funders and ethical innovators in the private sector consider and respond to when designing future regulations, policies or initiatives around data use and governance.

This report also acknowledges the need to prepare the ground for the more ambitious transformation of power relations in the digital ecosystem. Even a well-targeted intervention won’t change the system unless it is supported by relevant institutions and behavioural change.

In addition to targeted interventions, the report explains the preconditions that can support change:

- Effective regulatory enforcement.

- Legal action and representation.

- Removal of industry dependencies.

Reconceptualising the digital ecosystem will require sustained, collective and thorough efforts, and an understanding that elaborating on strategies for the future involves constant experimentation, adaptation and recalibration.

Through discussion of each intervention, the report brings an initial set of provocative ideas and concepts, to inspire a thoughtful debate about the transformative changes needed for the digital ecosystem to start evolving towards a people and society-focused vision. These can help us think about potential ways forward, open up questions for debate instead of rushing to provide answers, and offer a starting point from which more fully fledged solutions for change are able to grow.

We hope that policymakers, researchers, civil society organisations, funders and ethical industry innovators will engage with – and, crucially, iterate on – these propositions in a collective effort to find solutions that lead to lasting change in data practices and policies.

Making data work for people and society

The building blocks for a people-first digital ecosystem start from repurposing data to respect individual agency and deliver societal benefits, and from addressing abuses that are well defined and understood today, and are likely to continue if they are not dealt with in a systemic way.

Making data work for people means protecting individuals and society from abuses caused by corporations’ or governments’ use of data and algorithms. This means fundamental rights such as privacy, data protection and non-discrimination are both protected in law and reflected in the design of computational processes that generate and capture personal data.

The requirement to protect people from harm does not only operate in the present, there is also a need to prevent harms from happening in the future, and to create resilient institutions that will operate effectively against future threats and potential impact that can’t be fully anticipated.

To produce long-lasting change, we will need to break structural dependencies and address the sources of power of big technology companies. To do this, one goal must be to create data governance models and new institutions that will balance power asymmetries. Another goal is to restructure economic, technical and legal tools and incentives, to move infrastructure control away from unaccountable organisations.

Finally, positive goals for society can emerge from data infrastructures and algorithmic models developed by private and/or public actors, if data serves both individual and societal goals, rather than just the interests of commerce or undemocratic regimes.

How to use this report

The report is written to be of particular use to policymakers, researchers, civil society organisations, funders and those working in data-governance. To understand how and where you can take the ideas explored here forward, we recommend these approaches:

- If you work on data policy decision-making, go through a brief overview of the sources of power in today’s digital ecosystem in Chapter 1, focus on ‘The vision’ subsections in and answer the call to action in Chapter 3 by considering ways to translate the proposed interventions into policy action and help build the pathway towards a comprehensive and transformative vision for data.

- If you are a researcher, focus on the ‘How to get from here to there’ and ‘Further considerations and provocative concepts’ subsections in Chapter 2 and answer the call to action in Chapter 3 by reflecting critically on the provocative concepts and help develop the propositions into more concrete solutions for change.

- If you are a civil society organisation, focus on ‘How to get from here to there’ subsections in Chapter 2 and answer the call to action in Chapter 3 by engaging with the suggested transformations and build momentum to help visualise a positive future for data and society.

- If you are a funder, go through an overview of the sources of power in today’s digital ecosystem in Chapter 1, focus on ‘The vision’ subsections in Chapter 2 and answer the Call to action in Chapter 3 by supporting the development of a proactive policy agenda by civil society.

- If you are working on data governance in industry, focus on sections 1 and 2 in Chapter 2, help design mechanisms for responsible generation and use of data, and answer the call to action in Chapter 3 by supporting the development of standards for open and rights enhancing systems.

Chapter 1: Understanding power in data-intensive digital ecosystems

1. Context setting

To understand why a transformation is needed in the way our digital ecosystem operates, it’s necessary to understand the dynamics and different facets of today’s data-intensive ecosystem.

In the last decade, there has been an exponential increase in the generation, collection and use of data. This upsurge is driven by an increasing datafication of everyday parts of our lives,2 from work to social interactions and, to the provision of public services. The backbone of this change is the growth of digitally connected devices, data infrastructures and platforms, which enable new forms of data generation and extraction at an unprecedented scale.

Estimates put the volume of data created and consumed from two zettabytes in 2010 to 64.2 zettabytes in 2020 (one zettabyte is a trillion gigabytes) and project that it will grow to more than 180 zettabytes up to 2025.3 These oft-cited figures disguise a range of further dynamics (such as the wider societal phenomena of discrimination and inequality that are captured and represented in these datasets), and the textured landscape of who and what is included in the datasets, what data quality means in practice, and whose objectives are represented in data processes and met through outcomes from data use.

Data is often promised to be transformative, but there remains debate as to exactly what it transforms. On one hand, data is recognised as an important economic opportunity, and policy focus across the globe and is believed to deliver significant societal benefits. On the other hand, increased datification and calculability of human interactions can lead to human rights abuses and illegitimate public or private control. In between these opposing views are a variety of observations that reflect the myriad ways data and society interact, broadly considering the ways such practices reconfigure activities, structures and relationships.4

According to scholars of surveillance and informational capitalism, today’s digital economy is built on deeply rooted, exploitative and extractive data practices.5 These result in the accrual of immense surpluses of value to dominant technology corporations, and a role for the human participants enlisted in value creation for these big technology companies that has been described as a form of ‘data rentiership’.6

Commentators differ, however, on the real source of the value that is being extracted. Some consider that value comes from data’s predictive potential, while others emphasise that the economic arrangements in the data economy allow for huge profits to be made (largely through the advertising-based business model) even if predictions are much less effective than technology giants claim.7

In practice, only a few large technology corporations – Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms (Facebook) and Microsoft – have the data, processing abilities, engineering capacity, financial resources, user base and convenience appeal to provide a range of services that are both necessary to smaller players and desired by a wide base of individual users.

These corporations extract value from their large volumes of interactions and transactions, and process massive amounts of personal and non-personal data in order to optimise the service and experience of each business or individual user. Some platforms have the ability to simultaneously coordinate and orchestrate multiple sensors or computers in the network, like smartphones or connected objects. This drives the platform’s ability to innovate and offer services that seem either indispensable or unrivalled.

While there is still substantial innovation outside these closed ecosystems, the financial power of the platforms means that in practice they are able to either acquire or imitate (and further improve) innovations in the digital economy. Their efficiency in using this capacity enables them to leverage their dominance into new markets. The acquisition of open-source code platforms like GitHub by Microsoft in 2018 and RedHat by IBM in 2019 also points to a possibility that incumbents intend to extend their dominance to open-source software. The difficulty new players face to compete makes the largest technological players seem unmovable and unchangeable.

Over time, access to large pools of personal data has allowed platforms to develop services that now represent and influence the infrastructure or underlying basis for many public and private services. Creating ever-more dependencies in both public and private spheres, large technology companies are extending their services to societally sensitive areas such as education and health.

This influence has become more obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, when large companies formed contested public-private partnerships with public health authorities.8 They also partnered among themselves to influence contact tracing in the pandemic response, by facilitating contact tracing technologies in ways that were favourable or unfavourable to particular nation states. This revealed the difficulty, even at state level, of engaging in advanced use of data without the cooperation of the corporations that control the software and hardware infrastructure.

Focusing on data alone is insufficient to understand power in data-intensive digital systems. A vast number of interrelated factors consolidate both economic and societal power of particular digital platforms.9 These factors go beyond market power and consumer behaviour, and extend to societal and democratic influence (for example through algorithmic curation and controlling how human rights can be exercised).10

Theorists of platform governance highlight the complex ways in which vertically integrated platforms make users interacting with them legible to computers, and extract value by intermediating access to them.11

This makes it hard to understand power from data without understanding complex technological interactions up and down the whole technology ‘stack’, from the basic protocols and connectivity that underpin technologies, through hardware, and the software and cloud services that are built on them.12

Large platforms have become – as a result of laissez-faire policies (minimal government intervention in market and economic affairs) rather than by deliberate, democratic design – one of the building blocks for data governance in the real world, unilaterally defining the user experience and consumer rights. They have used a mix of law, technology and economic influence to place themselves in a position of power over users, governments, legislators and private-sector developers, and this has proved difficult to dislodge or alter.13

2. Rethinking regulatory approaches in digital markets

There is a recent, growing appetite to regulate both data and platforms using a variety of legal approaches to regulate market concentration, platforms as public spheres, and data and AI governance. The year 2021 alone marked a significant global uptick in proposals for the regulation of AI technologies, online markets, social media platforms and other digital technologies, with more still to come in 2022.14

A range of jurisdictions are reconsidering the regulation of digital platforms both as marketplaces and places of public speech and opinion building (‘public spheres’). Liability obligations are being reanalysed, including in bills around ‘online harms’ and content moderation. The Online Safety Act in Australia,15 India’s Information Technology Rules,16 the EU’s Digital Services Act17 and the UK’s draft Online Safety Bill18 are all pieces of legislation that seek to regulate more rigorously the content and practices of online social media and messaging platforms.

Steps are also being made to rethink the relationship between competition, data and platforms, and jurisdictions are using different approaches. In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority launched the Digital Markets Unit, focusing on a more flexible approach, with targeted interventions in competition in digital markets and codes of conduct.19 In the EU, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) takes a top-down approach and establishes general rules for large companies that prohibit certain practices up front, such as combining or cross-using personal data across services without users’ consent, or giving preference to their own services and products in rankings.20 India is also responding to domestic market capture and increased influence from large technology companies with initiatives such as the Open Network for Digital Commerce, which aims to create a decentralised and interoperable platform for direct exchange between buyers and sellers without intermediary services such as Amazon.21 At the same time, while the draft 2019 Indian Data Protection Bill is being withdrawn, a more comprehensive legal framework is expected in 2022 covering – alongside privacy and data protection – broader issues such as non-personal data, regulation of hardware and devices, data localisation requirements and rules to seek approval for international data transfers.22

Developments in data and AI policy

Around 145 countries now have some form of data privacy law, and many new additions or revisions are heavily influenced by legislative standards including the Council of Europe’s Convention 108 + and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).23

The GDPR is a prime example of legislation aimed at curbing the worst excesses of exploitative data practices, and many of its foundational elements are still being developed and tested in the real world. Lessons learned from the GDPR show how vital it is to consider power within attempts to create more responsible data practices. This is because regulation is not just the result of legal design in isolation, but is also shaped by immense corporate lobbying,24 applied within organisations via their internal culture and enforced in a legal environment that gives major corporations tools to stall or create disincentives to enforcement.

In the United States, there have been multiple attempts at proposing privacy legislation,25 and there is growing momentum with privacy laws being adopted at the state level.26 A recent bipartisan privacy bill proposed in June 202227 includes broad privacy provisions, with a focus on data minimisation, privacy by design and by default, loyalty duties to individuals and the introduction of a private right to action against companies. So far, the US regulatory approach to new market dynamics has been a suite of consumer protection, antitrust and privacy laws enforced under the umbrella of a single body, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which has a broad range of powers to protect consumers and investigate unethical business practices.28

Since the 1990s, with very few exceptions, the US technology and digital markets have been dominated by a minimal approach to antitrust intervention29 (which is designed to promote competition and increase consumer welfare). Only recently has there been a revival of antitrust interventions in the US with a report on competition in the digital economy30 and cases launched against Facebook and Google.31

In the UK, a consultation launched in September 2021 proposed a number of routes to reform the Data Protection Act and the UK GDPR.32 Political motivations to create a ‘post-Brexit’ approach to data protection may test ‘equivalence’ with the European Union, to the detriment of the benefits of coherence and seamless convergence of data rights and practices across borders.

There is also the risk that the UK lowers levels of data protection to try to increase investment, including by large technology companies operating in the UK, therefore reinforcing their market power. Recently released policy documents containing significant changes are the National Data and AI Strategies,33 and the Government’s response to the consultation on the reforms to the data protection framework,34 followed by a draft bill published in July 2022.35

Joining the countries that have developed AI policies and national strategies,36 Brazil,37 the USA38 and the UK39 launched their own initiatives, with regulatory intentions ranging from developing ethical principles and guidelines for responsible use, to boosting research and innovation, to becoming a world leader, an ‘AI superpower’ and a global data hub. Many of these initiatives are industrial policy rather than regulatory frameworks, and focus on creating an enabling environment for the rapid development of AI markets, rather than mitigating risk and harms.40

In August 2021, China adopted its comprehensive data protection framework consisting of the Personal Information Protection Law,41 which is modelled on the GDPR, and the Data Security Law, which focuses on harm to national security and public interest from data-driven technologies.42 Researchers argue that understanding this unique regulatory approach should not start from a comparative analysis (for example to jurisdictions such as the EU, which focus on fundamental rights). They trace its roots to the Chinese understanding of cybersecurity, which aims to protect national polity, economy and society from data-enabled harms and defend against vulnerabilities.43

While some of these recent initiatives have the potential to transform market dynamics towards less centralised and less exploitative practices, none of them meaningfully contest the dominant business model of online platforms or promote ethical alternatives. Legislators seem to choose to regulate through large actors as intermediaries, rather than by reimagining how regulation could support a more equal distribution of power. In particular, attention must be paid to the way many proposed solutions tacitly require ‘Big Tech’ to stay big.44

The EU’s approach to platform, data and AI regulation

In the EU, the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA) bring a proactive approach to platform regulation, by prohibiting certain practices up front and introducing a comprehensive package of obligations for online platforms.

The DSA sets clear obligations for online platforms against illegal content and disinformation and prohibits some of the most harmful practices used by online platforms (such as using manipulative design techniques and targeted advertising based on exploiting sensitive data).

It mandates increased transparency and accountability for key platform services (such as providing the main parameters used by recommendation systems) and includes an obligation for large companies to perform systemic risk assessments. This is complemented with a mechanism for independent auditors and researchers to access the data underpinning the company’s risk assessment conclusions and scrutinise the companies’ mitigation decisions.

While this is undoubtedly a positive shift, the impact of this legislation will depend substantially on online platforms’ readiness to comply with legal obligations, their interpretation of new legal obligations and effective enforcement (which has proved challenging in the past, for example with the GDPR).

The DMA addresses anticompetitive behaviour and unfair market practices of platforms that – according to this legislation – qualify as ‘gatekeepers’. Next to a number of prohibitions (such as combining or cross-using personal data without user consent), which are aimed at preventing the gatekeepers’ exploitative behaviour, the DMA contains obligations that – if enforced properly – will lead to more user choice and competition in the market for digital services.

These include basic interoperability requirements for instant messaging services, as well as interoperability with the gatekeepers’ operating system, hardware and software when the gatekeeper is providing complementary or supporting services.45 Another is the right for business users of the gatekeepers’ services to obtain free-of-charge, high quality, continuous and real-time access to data (including personal data) provided or generated in connection with their use of the gatekeepers’ core service.46 End users will also have the right to exercise the portability of their data, both provided as well as generated through their activity on core services such as marketplaces, app stores, search and social media.47

The DMA and DSA do not go far enough in terms of addressing deeply rooted challenges, such as supporting alternative business models that are not premised on data exploitation or speaking to users’ expectations to be able to control algorithmic interfaces (such as the interface for content filtering/generating recommendations). Nor does it create a level playing field for new market players who would like to develop services that compete with the gatekeepers’ core services.

New approaches to data access and sharing are also seen with the adopted Data Governance Act (DGA)48 and the draft Data Act.49 The DGA introduces the concept of ‘data altruism’ (the possibility for individuals or companies to voluntarily share data for the public good), facilitates the re-use of data from public and private bodies, and creates rules for data intermediaries (providers of data sharing services that are free of conflicts of interests relating to the data they share).

Complementing this approach, the proposed Data Act aims at securing end users’ right to obtain all data (personal, non-personal, observed or provided) generated by their use of products such as wearable devices and related services. It also aims to develop a framework for interoperability and portability of data between cloud services, including requirements and technical standards enabling common European data spaces.

There is also an increased focus on regulating the design and use of data-driven technologies, such as those that use artificial intelligence (machine learning algorithms). The draft Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) follows a risk-based approach that is limited to regulating ‘unacceptable’ and high-risk AI systems, such as prohibiting AI uses that pose a risk to fundamental rights or imposing ex ante design obligations on providers of high-risk AI systems.50

Perhaps surprisingly, the AI Act, as proposed by the European Commission, does not impose any transparency or accountability requirements on systems that pose less than high risk (with the exception of AI system that may deceive or confuse consumers), which include the dominant commercial business-to-consumer (B2C) services (e.g. search engines, social media, some recommendation systems, health monitoring apps, insurance and payment services).

Regardless of the type of risk (high-risk or limited-risk), this approach leaves a significant gap in accountability requirements for both large and small players that could be responsible for creating unfair AI systems. Responsibility measures should aim both at regulating the infrastructural power of large technology companies that supply most of the tools for ‘building AI’ (such as large language models, cloud computing power, text and speech generation and translation), as well as at creating responsibility requirements for smaller downstream providers who make use of these tools to construct their underlying services.

3. Weak enforcement response in digital markets

Large platforms are by their nature multi-sided, multi-sectoral and operate globally. The regulation of their commercial practices cuts across many sectors, and they are overseen by multiple bodies in different jurisdictions with varying degrees of expertise and in-house knowledge about how platforms operate. These include consumer protection authorities, data protection and competition authorities, non-discrimination and equal opportunities bodies, and financial markets, telecom regulators, media regulators, etc.).

It is well known that these regulatory bodies are frequently under-equipped for the task they are charged with, and there is an asymmetry between the resources available to them compared to the resources large corporations invest in neutralising enforcement efforts. For example, in the EU there is an acute lack of resources and institutional capacity: half the data protection authorities in the EU have an annual budget of €5 million or less, and 21 of the data protection authorities declare that their existing resources are not enough to operate effectively.51

A bigger problem is the lack of regulatory response in general, and recent lessons learned from insufficient data-protection enforcement responses show there needs to be a shift towards a stronger response from regulators, and a more proactive, collaborative approach to curbing exploitative and harmful activities, and bringing down illegal practices.

For example, in 2018 the first complaints against the invasive practices of the online advertising industry (such as real-time bidding, an online ad auctioning system that broadcasts personal data to thousands of companies)52 were filed with the Irish Data Protection Commissioner (Irish DPC) and with the UK’s Information Commissioner Office (ICO),53 two of the more resourceful – but still not sufficiently funded – authorities. Similar complaints followed across the EU.

After three years of inaction, civil society groups initiated court cases against the two regulators for lack of enforcement, as well as a lawsuit against major advertising and tracking companies.54 It was a relatively small regulator, the Belgian Data Protection Authority, that confirmed in its 2022 decision that those ad tech practices are illegal, showing that the lack of resources is not the sole cause for regulatory inertia.55

Some EU data protection authorities have been criticised for their reluctance to intervene in the technology sector. For example, it took three years from launching the investigation for the Irish regulator to issue a relatively small fine against WhatsApp for failure to meet transparency requirements under the GDPR.56 The authority is perceived as a key ‘bottleneck’ to enforcement because of its delays in delivering enforcement decisions,57 as many of the large US technology companies are established in Dublin.58

Some have suggested that ‘reform to centralise enforcement of the GDPR could help rein in powerful technology companies’.59

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) awards the European Commission the role of a sole enforcer against certain data-related practices performed by ‘gatekeeper’ companies (for example the prohibition of combining and cross-using personal data from different services without consent). The enforcement mechanism of the DMA gives powers to the European Commission to target selected data practices that may also infringe rules typically governed by the GDPR.

In the UK, the ICO has been subject to criticism for its preference for dialogue with stakeholders over formal enforcement of the law. Members of Parliament as well as civil society organisations have increasingly voiced their disquiet over this approach,60 while academics have queried how the ICO might be held accountable for its selective and discretionary application of the law.61

The 2021 public consultation led by the UK Government – Data: A New Direction – will do little to reassure those concerned, given the significant incursions into the ICO’s regulatory independence mooted.62 It remains to be seen whether subsequent consultations initiated by the ICO regarding its regulatory approach signal a shift from selective and discretionary application of law towards formal enforcement action.63

The measures proposed for consultation go even further towards removing some of the important requirements and guardrails against data abuses, which in effect will legitimise practices that have been declared illegal in the EU.64

Recognising the need for cooperation among different regulators

Examinations of abuses, market failure, concentration tendencies in the digital economy and market power of large platforms are more prominent. Extensive reports were commissioned by governments in the UK,65 Germany,66, the European Union,67 Australia68 and beyond, asking what transformations are necessary in competition policy, to address the challenges of the digital economy.

A comparison of these four reports highlights the problem of under-enforcement in competition policy and recommends a more active enforcement response.69 It also underlines that all the reports analyse the important interplay between competition policy and other policies such as data protection and consumer protection law.

The Furman report in the UK recommended the creation of a new Digital Markets Unit that collaborates on enforcement with regulators in different sectors and draws on their experience to form a more robust approach to regulating digital markets.65 In 2020, the UK Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF) was established to enhance cooperation between the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the Office of Communications (Ofcom) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and support a more coordinated regulatory approach.71

The need for more collaboration and joined-up thinking among regulators was highlighted by the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) in 2014.72 In 2016, the EDPS launched the Digital Clearinghouse initiative, an international voluntary network of enforcement bodies in different fields,73 however its activity has been limited.

Today there is still limited collaboration between regulators across sectors and borders because of a lack of legal basis for effective cooperation and exchange of information, including compelled and confidential information. Support for a more proactive and coherent regulatory enforcement must increase substantially to make a significant impact in terms of limiting the overwhelming power of large technology corporations in markets, over people and in democracy.

Chapter 2: Making data work for people and society

This chapter explores four cross-cutting interventions that have the potential to shift power in the digital ecosystem, especially if implemented in coordination with each other. These provocative ideas are offered with the aim to push forward the thinking around existing data policy and practice.

Each intervention is capable of integrating legal, technological, market and governance solutions that could help transition the digital ecosystem towards a people-first vision. While there are many potential approaches, for the purposes of this report – for clarity and ease of understanding –one type of potential solution or remedy is focused on under each intervention.

Each intervention is woven and connected to the others in a way that sets out a cross-cutting vision of an alternative data future, and which can frame forward-looking debates about data policy and practice. The vision these interventions offer will require social and political standing. Behind each intervention there is a promise of a positive change that needs the support and collaboration of policymakers, researchers, civil society organisations and industry practitioners to make them into a reality.

1. Transforming infrastructure through open ecosystems

The vision

Imagine a world in which digital systems have been transformed, and control over technology infrastructure and algorithms no longer lies in the hands of a few large corporations.

Transforming infrastructure means what was once a closed system of structural dependencies, which enabled large corporations to concentrate power, has been replaced by an open ecosystem where power imbalances are reduced and people can shape the digital experiences they want.

No single company or subset of companies controls the full technological stack of digital infrastructures and services. Users can exert meaningful control over the ways an operating system functions on phones and computers, and actions performed by web browsers and apps.

The incentive structures that drove technology companies to entrench power have been dismantled, and new business models are more clearly aligned with user interests and societal benefits. This means there are no more ‘lock in’ models, in which users find it burdensome to switch to another digital service provider, and fewer algorithmic systems that are optimised to attract clicks, prioritising advertising revenue over people’s needs and interests.

Instead, there is competition and diversity of digital services for users to choose from, and these services use interoperable architectures that enable users to switch easily to other providers and mix-and-match services of their choice within the same platform. For example, third-party providers create products that enable users to seamlessly communicate on social media channels from a standalone app. Large platforms allow their users to change the default content curation algorithm to the one of their choice.

Thanks to full horizontal and vertical interoperability, people using digital services are empowered to choose their favourite or trusted provider of infrastructure, content and interface. Rather than platforms setting rules and objectives that determine what information is surfaced by their recommender system, third-party providers, including reputable news organisations and non-profits, can build customised filters (operating on the top of default recommender systems to modify the newsfeed) or design alternative recommender systems.

All digital platforms and service providers operate within high standards of security and protection, which are audited and enforced by national regulators. Following new regulatory requirements, large platforms operate under standard protocols that are designed to respect choices made by their users, including strict limitations on the use of their personal data.

How to get from here to there

In today’s digital markets, there is unprecedented consolidation of power in the hands of a few, large US and Chinese digital companies. This tendency towards centralised power is supported by the current abilities of platforms to:

- process substantial quantities of personal and non-personal data, to optimise their services and the experience of each business or individual user

- extract market-dominating value from large-volume interactions and transactions

- use their financial power to either acquire or imitate (and further improve) innovations in the digital economy

- use this capacity to leverage dominance into new markets

- use financial power to influence legislation and stall enforcement through litigation.

The table below takes a more detailed look at some of the sources of power and possible remedies.

These dynamics reduce the possibility for new alternative services to be introduced and contribute to users’ inability to switch services and to make value-based decisions (for example, to choose a privacy-optimised social media application, or to determine what type of content is prioritised on their devices).74 Instead, a few digital platforms have the ability to capture a large user base and extract value from attention-maximising algorithms and ‘dark patterns’ – deceptive design practices that influence users’ choices and encourage them to take actions that result in more profit for the corporation, often at the expense of the user’s rights and digital wellbeing.75

As discussed in Chapter 1, there is still much to explore when considering possible regulatory solutions, and there are many possible approaches to reducing concentration and market dominance. Conceptual discussions about regulating digital platforms that have been promoted in policy and academia range from ‘breaking up big tech’,76 by separating the different services and products they control into separate companies, to nationalising and transforming platforms into public utilities or conceiving of them as universal digital services.77 Alternative proposals suggest limiting the number of data-processing activities a company can perform concurrently, for example separating search activities from targeted advertising that exploits personal profiles.

There is a need to go further. The imaginary picture painted at the start of this section points towards an environment where there is competition and meaningful choice in the digital ecosystem, where rights are more rigorously upheld and where power over infrastructure is less centralised. This change in power dynamics would require, as one of the first steps, that digital infrastructure is transformed with full vertical and horizontal interoperability. The imagined ecosystem includes large online platforms, but in this scenario they find it much more difficult to maintain a position of dominance, thanks to real-time data portability, user mobility and requirements for interoperability stimulating real competition in digital services.

What is interoperability?

Interoperability is the ability of two or more systems to communicate and exchange information. It gives end users the ability to move data between services (data portability), and to access services across multiple providers.

How can interoperability be enabled?

Interoperability can be enabled by developing (formal or informal) standards that define a set of rules and specifications that, when implemented, allow different systems to communicate and work together. Open standards are created through the consensus of a group of interested parties and are openly accessible and usable by anyone.

This section explores a range of interoperability measures that can be introduced by national or European policy makers, and discusses further considerations to transform the current, closed platform infrastructure into an open ecosystem.

Introducing platform interoperability

Drawing from examples of other sectors that historically have operated in silos, mandatory interoperability measures are a potential tool that merit further exploration, to create new opportunities for both companies and users.

Interoperability is a longstanding policy tool in EU legislation and more recent digital competition reviews suggest it as a measure against highly concentrated digital markets.78

In telecommunications, interoperability measures make it possible to port phone numbers from one provider to another, and enable customers of one phone network to call and message customers on other networks, improving choice for consumers. In the banking sector, interoperability rules made it possible for third parties to facilitate account transfers from one bank to another, and to access data about account transactions to build new services. This opened up the banking market for new competitors and delivered new types of financial services for customers.

In the case of large digital platforms, introducing mandatory interoperability measures is one way to allow more choice of service (preventing both individual and business users from being trapped in one company’s products and services), and to re-establish the conditions to enable a competitive market for start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises to thrive.79

While some elements of interoperability are present in existing or proposed EU legislation, this section explores a much wider scope of interoperability measures than those that have already been adopted. (For a more detailed discussion on ‘Possible interoperability mandates and their practical implications’, see the text box below.)

Some of these elements of interoperability in existing or proposed EU legislation are:80

- The Digital Markets Act enables interoperability requirements between instant messaging services, as well as with the gatekeepers’ operating system, hardware and software (when the gatekeeper is providing complementary or supporting services), and strengthens data portability rights.81

- The Data Act proposal aims to enable switching between cloud providers.82

- Regulation on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services (‘platform-to-business regulation’) gives business users the right to access data generated through the provision of online intermediation services.83

These legislative measures address some aspects of interoperability, but place limited requirements on services other than instant messaging services, cloud providers and operating systems in certain situations.84 They also do not articulate a process for creating technical standards around open protocols for other services. This is why there is a need to test more radical ideas, such as mandatory interoperability for large online platforms covering both access to data and platform functionality.

Possible interoperability mandates and their practical implications

Ian Brown

Interoperability in digital markets requires some combination of access to data and platform functionality.

Data interoperability

Data portability (Article 20 of the EU GDPR) is the right of a user to move their personal data from one company to another. (The Data Transfer Project developed by large technology companies is slowly developing technical tools to support this.85) This should help an individual switch from one company to another, including by giving price comparison tools access to previous customer bills.

However, a wider range of uses could be enabled by real-time data mobility86 or interoperability,87 implying that an individual can give one company permission to access their data held by another, and meaning it can be updated whenever they use the second service. These remedies can stand alone, where the main objective is to enable individuals to give access to their personal data held by an incumbent firm to competitors.

Scholars make an additional distinction between syntactic or technical interoperability, the ability for systems to connect and exchange data (often via Application Programming Interfaces or ‘APIs’) and semantic interoperability, that connected systems share a common understanding of the meaning of data they exchange.88

An important element of making both types of data-focused interoperability work is developing more data standardisation to require datasets to be structured, organised, stored and transmitted in more consistent ways across different devices, services and systems. Data standardisation creates common ontologies, or classifications, that specify the meaning of data.89

For example, two different instant messaging services would benefit from a shared internal mapping of core concepts such as identity (phone number, nickname, email), rooms (public or private group chats, private messaging), reactions, attachments, etc. – these are concepts and categories that could be represented in a common ontology, to bridge functionality and transfer data across these services.90

Data standardisation is an essential underpinning for all types of portability and interoperability and, just like the development of technical standards for protocols, it needs both industry collaboration and measures to ensure powerful companies do not hijack standards to their own benefit.

An optional interoperability function is to require companies to support personal data stores (PDS), where users store and control data about them using a third-party provider and can make decisions about how it is used (e.g. the MyData model91 and Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee’s Solid project).

The data, or consent to access it, could be managed by regulated aggregators (major Indian banks are developing a model where licensed entities aggregate account data with users’ consent and therefore act as an interoperability bridge between multiple financial services),92 or facilitated by user software through an open set of standards adopted by all service providers (as in the UK’s Open Banking). It is also possible for service providers to send privacy-protective queries or code to run on personal data stores inside a protected sandbox, limiting the service provider’s access to data (e.g. a mortgage provider could send code, checking an applicant’s monthly income was above a certain level, to their PDS or current account provider, without gaining access to all of their transaction data).93

The largest companies currently have a significant advantage in their access to very large quantities of user data, particularly when it comes to training machine learning systems. Requiring access to statistical summaries of the data (e.g. popularity of specific social media content and related parameters) may be sufficient, while limiting the privacy problems caused. Finally, firms could be required to share the (highly complex) details of machine learning models, or provide regulators and third-parties access to them to answer specific questions (such as the likelihood a given piece of social-media content is hate speech).

The interoperability measures described above would enable a smoother transfer of data between digital services, and enable users to exert more control over what kind of data is shared and in what circumstances. This would make for a ‘cleaner’ data ecosystem, in which platforms and services are no longer incentivised to gather as much data as possible on every user.

Rather, users would have more power to determine how their data is collected and shared, and smaller services wouldn’t need to engage in extractive data practices to ‘catch up’ with larger platforms, as barriers to data access and transfer would be reduced. The overall impact on innovation would depend on whether increased competition resulting from data sharing at least counterbalanced these reduced incentives.

Functionality-oriented interoperability

Another form of interoperability relates to enabling digital services and platforms to work cross-functionally, which could improve user choice in the services they use and reduce the risk of ‘lock in’ to a particular service. Examples of functionality-oriented interoperability (sometimes referred to as protocol interoperability,94 or in telecoms regulation, interconnection of networks) include:

- the ability for a user of one instant-messaging service to send a message to a user or group on a competing service

- the user of one social media service can ‘follow’ a user on another service, and ‘like’ their shared content

- the ability of a user of a financial services tool to initiate a payment from an account held with a second company

- the user of one editing tool can collaboratively edit a document or media file with the user of a different tool, hosted on a third platform.

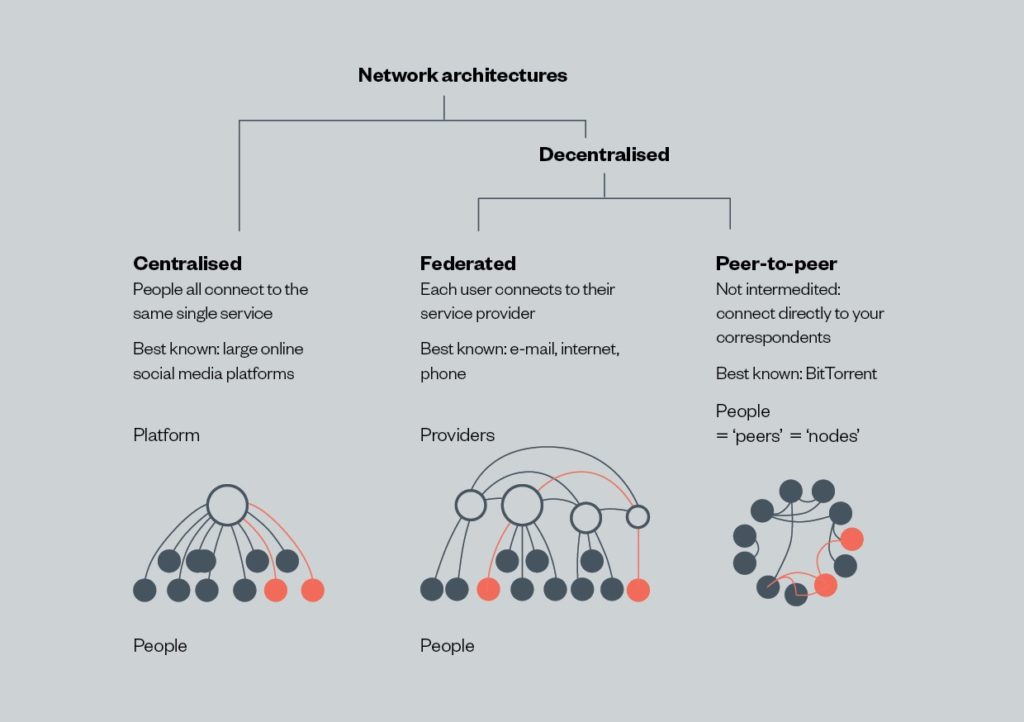

Services communicate with each other using open/publicly accessible APIs and/or standardised protocols. In Internet services, this generally looks like the ‘decentralised’ network architectures shown below:

The UK’s Open Banking Standard recommended: ‘The Open Banking API should be built as an open, federated and networked solution, as opposed to a centralised/hub-like approach. This echoes the design of the Web itself and enables far greater scope for innovation.’95

An extended version of functional interoperability would allow users to exercise other forms of control over the products and services they use, including:

- signalling their preferences to platforms on profiling – the recording of data to assess or predict their preferences – using a tool such as the Global Privacy Control, or expressing their preferred default services such as search

- replacing core platform functionality, such as a timeline ranking algorithm or an operating system default mail client, with a preferred version from a competitor (known as modularity)96

- using their own choice of software to interact with the platform.

Noted competition economist Cristina Caffarra has concluded: ‘We need wall-to-wall [i.e. near-universal] interoperability obligations at each pinch point and bottleneck: only if new entrants can connect and leverage existing platforms and user bases can they possibly stand a chance to develop critical mass.’97 Data portability alone is a marginal solution (and a limited remedy for GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook (now Meta Platforms), Amazon, Microsoft) when those companies want to flag their good intentions.98 A review of portability in the Internet of Things sector came to a similar conclusion.99

Further considerations and provocative concepts

Mandatory interoperability measures have the potential to transform digital infrastructure, and to enable innovative services and new experiences for users. However, they need to be supported by carefully considered additional regulatory measures, such as cybersecurity, data protection and related accountability frameworks. (See text box below on ‘How to address sources of platform power? Possible remedies’ for an overview of interoperability and data protection measures that could tackle some of the sources of power for platforms.)

Also, the development of technical standards for protocols and classification systems or ontologies specifying the meaning of data (see text box above on ‘Possible interoperability mandates and their practical implications’) is foundational to data and platform interoperability. However, careful consideration must be placed on designing new types of infrastructure, in order to prevent platforms from consolidating control. Examples from practice show that developing open standards and protocols are not enough on their own.

Connected to the example above on signalling preferences to platforms, open protocols such as the ‘Do Not Track’ header were meant to help users more easily exercise their data rights by signalling an opt-out preference from website tracking.100 In this case, the standardisation efforts stopped due to insufficient deployment,101 demonstrating the significant challenge in obliging platforms to facilitate the use of standards in the services they deploy.

A final point relates to creating interoperable systems that do not overload users with too many choices. Already today it is difficult for users to manage all the permissions they give across all the services and platforms they use. Interoperability may offer solutions for users to share their preferences and permissions for how their data should be collected and used by platforms, without requiring recurring ‘cookie notice’-type requests to a user when using each service.

How to address sources of platform power? Possible remedies

Ian Brown

Interoperability and related remedies have the potential to address not only problems resulting from market dominance of a few large firms, but – more importantly – some of the sources of their market power. However, every deep transformation needs to be carefully designed to prevent unwanted effects. The challenges associated with designing market interventions based on interoperability mandates need to be identified early in the policy- making process so that problems can either be solved or accounted for.

The table below presents specific interoperability measures, classified by their potential to address various sources of large platforms’ power, next to problems that are likely to result from their implementation.

While much of the policy debate so far on interoperability remedies has taken place within a competition-law framework (including telecoms and banking competition), there are equally important issues to consider under data and consumer protection law, as well as useful ideas from media regulation. Competition-focused measures are generally applied only to the largest companies, while other measures can be more widely applied. In some circumstances these measures can be imposed under existing competition-law regimes on dominant companies in a market, although this approach can be extremely slow and resource-intensive for enforcement agencies.

The EU Digital Markets Act (DMA), and US proposals (such as the ACCESS Act and related bills), impose some of these measures up-front on the very largest ‘gatekeeper’ companies (as defined by the DMA). The European Commission has also introduced a Data Act that includes some of the access to data provisions below.82 Under these measures, smaller companies are free to decide whether to make use of interoperability features that their largest competitors may be obliged to support.

| Sources of market power for large firms/platforms | Proposed interoperability or related remedies | Potential problems |

| Access to individual customer data (including cross-use of data from multiple services) | Real-time and continuous user-controlled data portability/data interoperability

Requirement to support user data stores (Much) stricter enforcement of data minimisation and purpose limitation requirements under data protection law, alongside meaningful transparency about reasons for data collection (or prohibiting certain data uses cross-platform) |

Need for multiple accounts with all services, and take-it-or-leave-it contract terms

Incentive for mass collection, processing and sharing of data, including profiling |

| Access to large-scale raw customer data for analytics/product improvement | Mandated competitor access to statistical data103

*Mandated competitor access to raw data is dismissed because of significant data protection issues |

Reduced incentives for data collection |

| Access to large-scale aggregate/statistical customer data | Mandated competitor access to models, or specific functionality of models via APIs | Reduced incentives for data collection and model training |

| Ability to restrict competitor interaction with customers | Requirement to support open/publicly accessible APIs or standardised communications protocols | Complexity of designing APIs/standards, while preventing anticompetitive exclusion |

| Availability and use of own core platform services to increase ‘stickiness’ | Government coordination and funding for development of open infrastructural standards and components

Requirement for platforms to support/integrate these standard components |

Technical complexity of full integration of standard/competitor components into services/design of APIs while preventing anticompetitive exclusion

Potential pressure for incorporation of government surveillance functionality in standards |

| Ability to fully control user interface, such as advertising, content recommendation, specific settings, or self-preferencing own services | Requirement to support competitors’ monetisation and filtering/recommendation services via open APIs104

Requirement to present competitors’ services to users on an equal basis105 Requirement to recognise specific user signals Open APIs to enable alternative software clients |

Technical complexity of full integration of competitor components into services/design of APIs while preventing anticompetitive exclusion |

Food for thought

In the previous section strong data protection and security provisions were emphasised as essential for building an open ecosystem that enables more choice for users, respects individual rights and facilitates competition.

Going a step further, there is a discussion to be had about boundaries of system transformation that seem achievable with interoperability. What are the ‘border’ cases, where the cost of transformation outweighs its benefits? What immediate technical, societal and economic challenges can be identified, when imagining more radical implementations of interoperability than those that have already been tested or are being proposed in EU policy?

In order to trigger further discussion, a set of problems and questions are offered as provocations:

- Going further, imagine a fully interoperable ecosystem, where different platforms can talk to each other. What would it mean to apply a full interoperability mandate across different digital services and what opportunities would it bring? For example, provided that technical challenges are overcome, what new dynamics would emerge if a Meta Platforms (Facebook) user could exchange messages with Twitter, Reddit or TikTok users without leaving the platform?

- More modular and customisable platform functionalities may change dynamics between users and platforms and lead to new types of ecosystems. How would the data ecosystem evolve if core platform functionalities were opened up? For example, if users could choose to replace core functionalities such as content moderation or news feed curation algorithms with alternatives offered by independent service providers, would this bring more value for individual users and/or societal benefit, or further entrench the power of large platforms (becoming indispensable infrastructure)? What other policy measures or economic incentives can complement this approach in order to maximise its transformative potential and prevent harms?

- Interoperability measures have produced important effects in other sectors and present a great potential for digital markets. What lessons can be learned from introducing mandatory interoperability in the telecommunications and banking sectors? Is there a recipe for how to open up ecosystems with a ‘people-first’ approach that enables choice while preserving data privacy and security, and provides new opportunities and innovative services that benefit all?

- Interoperability rules need to be complemented and supported by measures that take into account inequalities and make sure that the more diverse portfolio of services that is created through interoperability is accessible to the less advantaged. Assuming more choice for consumers has already been achieved through interoperability mandates, what other measures need to be in place to reduce structural inequalities that are likely to keep less privileged consumers locked in the default service? Experience from the UK energy sector shows that it is often the consumers/users with the fewest resources who are least likely to switch services and benefit from the opportunity of choice (the ‘poverty premium’).106

2. Reclaiming control of data from dominant companies

The vision

In this world, the primary purpose of generating, collecting, using, sharing and governing data is to create value for people and society. The power to make decisions about data has been removed from the few large technology companies who controlled the data ecosystem in the early twenty-first century, and is instead delegated to public institutions with civic engagement at a local and national level.

To ensure that data creates value for people and society, researchers and public-interest bodies oversee how data is generated, and are able to access and repurpose data that traditionally has been collected and held by private companies. This data can be used to shape economic and social policy, or to undertake research into social inequalities at the local and national level. Decisions around how this data is collected, shared and governed are overseen by independent data access boards.

The use of this data for societally beneficial purposes is also carefully monitored by regulators, who provide checks and balances on both private companies to share this data under high standards of security and privacy, and on public agencies and researchers to use that data responsibly.

In this world, positive results are being noticed from practices that have become the norm, such as developers of data-driven systems making their systems more auditable and accessible to researchers and independent evaluators. Platforms are now fully transparent about their decisions around how their services are designed and used. Designers of recommendation systems publish essential information, such as the input variables and optimisation criteria used by algorithms and results of their impact assessments, which supports public scrutiny. Regulators, legislators, researchers, journalists and civil society organisations easily interrogate algorithmic systems, and have a straightforward understanding over what decisions systems may be rendering and how those decisions impact people and society.

Finally, national governments have launched ‘public-interest data companies’, which collect and use data under strict requirements for objectives that are in the public interest. Determining ‘public interest’ is a question these organisations routinely return to through participatory exercises that empower different members of society

The importance of data in the digital market triggers the question how control over data and algorithms can be shifted away from dominant platforms, to allow individuals and communities to be involved in decisions about how their data is used. The imaginary scenario above builds a picture of a world where data is used for public good, and not (only) for corporate gain.

Current exploitative data practices are based on access to large pools of personal and non-personal data and the capacity to efficiently use data to extract value by means of advanced analytics.107

The insights into social patterns and trends that are gained by large companies through analysing vast datasets currently remain closed off and are used for extracting and maximising commercial gains, where they could have considerable social value.

Determining what constitutes uses of data for ‘societal benefit’ and ‘public interest’ is a political project that must be undertaken with due regard for transparency and accountability. Greater mandates to access and share data must be accompanied by strict regulatory oversight and community engagement to ensure these uses deliver actual benefit to individuals impacted by the use of this data.

The previous section discussed the need to transform infrastructure in order to rebalance power in the digital ecosystem. Another and interrelated foundational area where more profound legal and institutional change is needed is in control over data.

Why reclaim control over data?

For the purposes of this proposition, reflecting the focus on creating more societal benefit, the first goal of reclaiming control over data is to open up access to data and resources from companies and repurposing them for public-interest goals, such as developing public policies that take into consideration insights and patterns from large-scale datasets. A second purpose is to open up access to data and to machine-learning algorithms, in order to increase scrutiny, accountability and oversight over how proprietary algorithms function and to understand their impact at the individual, collective and societal level.

How to get from here to there

Proprietary siloing of data is currently one of the core obstacles to using data in societally beneficial ways. But simply making data more shareable, without specific purposes and strong oversight can lead to greater abuses rather than benefits. To counter this, there is a need for:

- legal mandates that private companies make data and resources available for public interest purposes

- regulatory safeguards to ensure this data is shared securely and with independent oversight.

Mandating companies share data and resources in the public interest

One way to reclaim control over data and repurpose it for societal benefits is to create legal mandates requiring companies to share data and resources that could be used in the public interest. For example:

- Mandating the release from private companies of personal and non-personal aggregate data for public use (where aggregate data means a combination of individual data, which is anonymised through eliminating personal information).108 These datasets would be used to inform public policies (e.g. use mobility patterns from a ride-sharing platform to develop better road infrastructure and traffic management).109

- Requiring companies to create interfaces for running data queries on issues of public interest (for example public health, climate, pollution, etc). This model relies on using the increased processing and analytics capabilities inside a company, instead of asking for access to large ‘data dumps’, which might prove difficult and resource intensive for public authorities and researchers to process. Conditions need to be in place around what types of queries are allowed, who can run these and what are the company’s obligations around providing responses.

- Providing access for external researchers and regulators to machine learning models and core technical parameters of AI systems, which could enable evaluation of an AI system’s performance and real optimisation goals (for example checking the accuracy and performance of content moderation algorithms for hate speech).

Some regulatory mechanisms are emerging at national and regional level in support of data access mandates. For example, in France, the 2016 Law for a Digital Republic (Loi pour une République numérique) introduces the notion of ‘data of general interest’ which includes access to data from private entities that have been delegated to run a public service (e.g. utility or transportation), access to data from entities whose activities are subsidised by public authorities, and access to certain private databases for the statistical purposes.110

In Germany, the 2019 leader of the Social Democratic Party championed a ‘data for all’ law that advocated for a ‘data commons’ approach and breaking-up data monopolies through a data-sharing obligation for market-dominant companies.111 In the UK, the Digital Economy Act provides a legal framework for the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to access data held within the public and private sectors in support of statutory functions to produce official statistics and statistical research.112

The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) includes a provision on data access for independent researchers.113

Under the DSA, large companies will need to comply with a number of transparency obligations, such as creating a public database of targeted advertisement and providing more transparency around how recommender systems work. It also includes an obligation for large companies to perform systemic risk assessments and to implement steps to mitigate risk.

In order to ensure compliance with the transparency provisions in the regulation, the DSA mandates independent auditors and vetted researchers with access to the data that led to the company’s risk assessment conclusions and mitigation decisions. This provision ensures oversight over the self-assessment (and over the independent audit) that companies are required to carry out, as well as scrutiny over the choices large companies make around their systems.

Other dimensions of access to data mandates can be found in the EU’s Data Act proposal, which introduces compulsory access to company data for public-sector bodies in exceptional situations (such as public emergencies or where it is needed to support public policies and services).82 The Data Act also provides for various data access rights, such as a right for individuals and businesses to access the data generated from the products or related service they use and share the data with a third party continuously and in real-time115 (companies which fall under the category of ‘gatekeepers’ are not eligible to receive this data).116

This forms part of the EU general governance framework for data sharing in business-to-consumer, business-to-business and business-to-government relationships created by the Data Act. It complements the recently adopted Data Governance Act (focusing on voluntary data sharing by individuals and businesses and creating common ‘data spaces’) and the Digital Markets Act (which strengthens access by individual and business users to data provided or generated through the use of core platform services such as marketplaces, app stores, search, social media, etc.).117

Independent scrutiny of data sharing and AI systems

Sharing data for the ‘public interest’ will require novel forms of independent scrutiny and evaluation, to ensure such sharing is legitimate, safe, and has positive societal impact. In cases where access to data is involved, concerns around privacy and data security need to be acknowledged and accounted for.

In order to mitigate some of these risks, one recent model proposes a system of governance in which a new independent entity would assess the researchers’ skills and capacity to conduct research within ethical and privacy standards.118 In this model, an independent ethics board would review the project proposal and data protection practices for both the datasets and the people affected by the research. Companies would be required to ‘grant access to data, people, and relevant software code in the form researchers need’ and refrain from influencing the outcomes of research or suppressing findings.119

An existing model for gaining access to platform data is Harvard’s SocialScienceOne project,120 which partnered with Meta Platforms (Facebook) in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal to control access to a dataset containing public URLs shared and clicked by Facebook users globally, along with metadata including Facebook likes. Researchers requests for access to the dataset go to an academic advisory board that is independent from Facebook, and which reviews and approves applications.